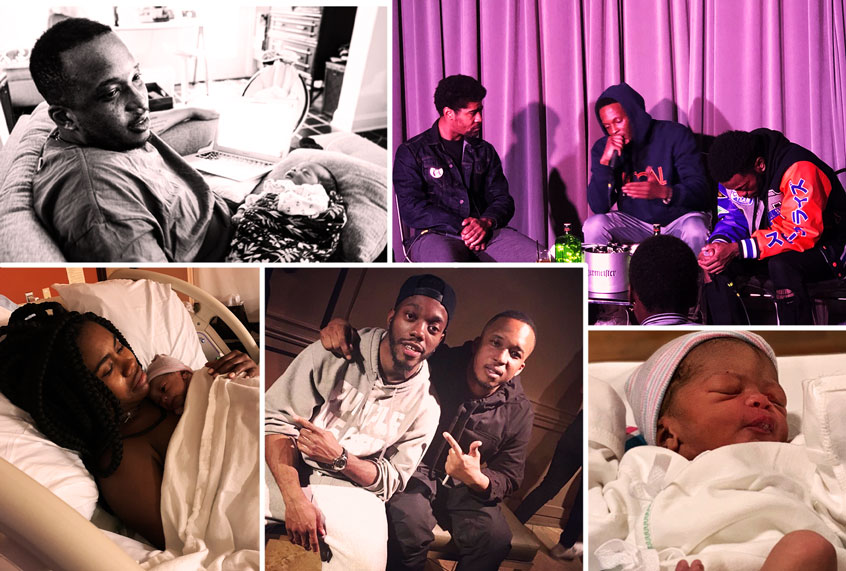

It’s a little after 8 p.m. on January 14, 2020, and I’m posted up at a table at Motor House, the studio/bar where my one of my best friends, photographer Devin Allen, hosts the monthly Artist Talks series. I keep an eye on my phone waiting for a text from my wife Caron as I wait for my turn on stage, while friends and friends of friends bring rounds of drinks around. The mood is celebratory but we aren’t celebrating anything specific, exactly. It’s not a particularly special day in America, but every day above ground in Baltimore is kind of special. We’re a relatively small city with an extremely high murder rate, and we had just closed out 2019 with 348 homicides.

At this event, Devin interviews local creators on stage over drinks. A group of artists, including me, had been invited that night to recap the work we did in 2019 and share what we were planning for 2020. Liquor flows in streams running in every direction at this event, so I couldn’t ask my pregnant wife to endure that. The plan was for me to hit the venue, give my portion of the talk and, by the time I was set to leave, probably get a text from her telling me, hey baby, bring a shrimp sub home. It was getting close to her due date, and I wanted to be home with her.

“Baby, text me if you want something else to eat, a shrimp sub or something,” I had said to her on the phone as I made my way to the front door of our home. “The event shouldn’t be that long. I’ll be right home afterwards.”

“Don’t drink too much,” she warned.

I probably should’ve stayed home, though. We didn’t know that she was already in labor.

“Yoooo, bro!” I hear a voice as I park. “Didn’t know you was coming out tonight!”

My good friend Dee Dave, a popular Baltimore rapper who’s always grinning and hungry to trade ideas, goals and plans, walks up on me wearing a cool letter jacket that I jokingly tell him I’m going to steal.

“Surprised you ain’t out on tour knocking those books off,” he says. “I gotta read ya new one. I’m honored that you put me in there!”

“Come on man, we family,” I reply. “And I’m home for now, bro. My baby girl will be here any day now.”

His big eyes grow bigger and he gives me a pound, then a firm hug.

“That’s love, bro! No better joy than being a father! Come inside, lemme grab you one!”

Elbow- and excuse-me-room-only wait on the other side of the door, each and every wall lined with paintings floating over seasoned and up-and-coming artists alike. If you wanted to delete the art scene in Baltimore and the bulk of its fans, all you had to do was drop a bomb on Motor House that night. Lucky for me and Dee Dave, we didn’t need to worry about drinks; Devin’s event sponsor supplied more than enough for his featured artists.

“Devin!” I call out, pulling him away from three conversations. “Put me on stage ASAP, bro. I gotta get home!”

9 p.m. I’m pinned against the wall now, with six rounds of drinks lined up in front of me — some clear, some brown, some mixed — and a bunch of yelling, rapping, laughing, celebrating, weirdly-dressed people trying to make me play catch-up, daring me to drink this and drink that. I hold my initial cup and sip slowly. As they talk and joke and prep to sit down with Devin on stage, I slowly give away the drinks they’ve lined up for me to other people, or even back to them as if I bought that round, and they don’t even notice.

“Yo, we headed up to the stage,” Dee Dave tells me. “Let’s go!”

I sit back and watch Dee Dave with one of his rap partners — and my close friend — FMG Dez join Devin on stage. They talk about rap, life, family and the love they have for our city. Dee Dave shares his victories and welcomes his struggles in the music industry with insurmountable love. So many people quit, so many artists stop; he can’t imagine that. His words shed light on all of our difficult industries, leaving me with a new hunger to be better, with a new sense of urgency. Energized, I hit the stage a few minutes later with that same fire, following his lead in an effort to motivate the audience. After my talk, Dee Dave and I finally grab that drink and toast to the moves we plan on making in 2020. I made it through the night, hitting my two-drink max, but one more wouldn’t hurt. After all, 2019 had been rough, and we need to celebrate those wins.

“Yo, remember you made my album a couple years back?” Dee Dave laughs. “We gotta bring you back!”

“Yooooo, lemme rap next time man, I’m ready!”

About four years ago, I recorded an intro on a Dee Dave track called “Take it Away.” I didn’t really have a plan before I entered the studio, and I’m not much of a rapper, even though I consume the music religiously. He told me to say something off the top of my head, so I came up with this: “We from East Baltimore man, so something’s gonna happen to you. Somebody’s gonna try you, you might get fucked up, you might fuck somebody up, you might get shot — but you gonna go through something. We got a whole lot to accomplish in a little bit of time. So what am I doing out there, if it’s not benefiting me, my family, or my team…”

“Yo, I gotta lil freestyle showcase coming up next week,” Dee Dave says. “You should come, bro!”

“I’ll be there,” I say as I toss up a peace sign and head to my car just in time to get the hey baby, bring a shrimp sub home text.

10 p.m. Caron’s big pregnancy craving was a fried shrimp sub with everything and extra hots from Bella Roma over in the Hampden section of Baltimore. Solid craving, decent sub. Like a good husband, I always deliver without asking too many questions. I present it to her like it’s an Academy Award or a championship belt. She looks really pleased, and then not so pleased. Her stomach’s upset; her appetite came and left, and maybe tried to come back again. I later found out that she had been experiencing contractions since 8 p.m. but hadn’t wanted to worry me in case it was a false alarm.

10:37 p.m. Caron sits down and peels the paper and foil off of the sandwich. “I’m really not feeling well,” she says. “Something’s different. These contractions are picking up. You think we should go to the hospital?”

We had prepared for this this moment: nine months of reading, talking, praying, thinking, planning, over-planning, making a playlist for the baby, naming the playlist after the baby. We made a packing list for an overnight suitcase for the hospital: night clothes, special breastfeeding bras, a Bluetooth speaker, scented candles, a lighter, a diffuser, and books. But we hadn’t gotten around to actually packing any of it. We throw it all into a suitcase, toss it into the back of my truck, and go. Caron tries to eat the sub as we make our way to the hospital. She knows this might be her last chance to eat for a while.

11 p.m. What is this baby going to look like? Is it really time? What if she weighs 15 pounds?

I let Caron off at the main entrance to the labor and delivery area of the hospital and park in the garage, conveniently located 2,000 miles away. I drag the suitcase through the maze of the hospital, and join my wife in a small examining room.

They tell us she had only dilated two centimeters, which wasn’t enough to really do anything. We couldn’t stay, but the nurse tells us not to check out, either. “Walk around the hospital and see what happens,” she says with a wink. The wink means we should go home and chill because the baby isn’t coming. But just in case she is, and we have to come back, we’d already be checked in.

1:30 a.m. We try to relax. Maybe we try to watch a movie or maybe we watch Ice T and Lt. Benson take down a rapist for the two-millionth time on “Law & Order SVU,” or maybe they watch us because Caron’s tossing and turning, walking back and forth, in and out of the bathroom, up and down the steps, and apparently the hospital staff moved too fast when they sent us home because the baby is definitely coming now.

“She has to be,” Caron says. “It’s time.”

We were expecting her in late January — the 23rd, to be exact. Apparently she was going to follow her own agenda.

4 a.m. Back at the hospital, we learn Caron is four centimeters dilated. The baby is taking her sweet little time, but she’s coming.

A snarky little blockhead nurse comes into the room and starts explaining the epidural procedure. My wife had planned to try to deliver our daughter naturally but wants a minute to weigh her options, and nurse block-head basically tells her to get the epidural or go home.

Caron isn’t against epidurals. Birth plans change all of the time. She just wants to make sure she’s making the right decision for her body. The nurse rolls her eyes and starts explaining the birth of a child to us as if we are children. I’m a writer, Caron’s a lawyer, and we’re both certified shit-talkers, so that ends quickly and poorly for the nurse.

Caron chooses the challenge of a natural birth.

“Do you know what that means?” the nurse asks again. “Do you understand what you are saying? Have you taken a birthing class?”

“Yes, we took one here, at this hospital,” Caron says.

We stand on the decision and dismiss nurse blockhead. And we refuse to let her kill our vibe.

7 a.m. This time, a really sweet team of nurses rolls in like three angels, smiling and nodding in unison. Their energy is calming — just what we needed after defeating the epidural lady in the previous room. They tells us everything is going to be OK and champion Caron for opting for the natural birth before exiting in a row, saying they’ll be back shortly.

We decide to pray.

10 a.m. The three nurses come back into the room to break Caron’s water.

I always thought the breaking of the water would be this big production — a stream of fluid bursting out like a geyser, or a broken fire hydrant washing us all across the room. I probably watch too much TV. When it happens to Caron, I don’t really see anything.

I set up the music and crack on the diffuser. A lavender scent fills the air, calming us even more as we wait. I light candles to heighten the effect, but one of the nurses says that’s a no-no. “You’re going to set the smoke alarms off.”

11 a.m. Caron breathes.

12:30 p.m. I walk up the hall to get an Einstein Bagel sandwich because I’m starving and the nurses say we were going be a minute. When I get back, bagel and egg grease smeared all over my mouth, like a pedestrian, I watch her glow, breathe, and run toward the pain in a mystical, unimaginable way.

1:15 p.m. I witness magic. Pure magic.

Women are strong and resilient in a way most men can’t comprehend. But this is different — it’s on another level. Caron vibes to the music, bopping her head and singing along to the R&B playlist. She smiles through tears. She breathes. She talks to the baby while rubbing her stomach, telling her that everything is going to be OK. She asks if I’m OK, as if I deserve that. It isn’t about me, it’s about her and our child, but she still stops to consider me even as I can’t even begin to understand what her body is going through, the fight she’s in to bring our baby into the world.

“Are OK? You are doing so well!” I say, though I grow more terrified by the minute. I don’t want my wife to die, or our baby to die, and this happens to black women far too often in this country, so often that I had to stop reading articles about the dangers black women face during childbirth.

The nurses come in and out to check on her, we love them more by the minute. “I hope this baby comes before they get off work!” Caron says.

“Nah, for real though,” I replied, “We don’t need any bad energy around us.”

Caron relaxes. Overwhelmed with everything, I’ve tired myself out, and I fall asleep. Her mom arrives and I wake to watch Caron squatting over a yoga ball, still breathing, still vibing, still magical. She moves between the bed and the yoga ball and back to the bed as the contractions grow stronger. I make jokes — not corny dad jokes, good ones to lighten the mood.

Family comes in and out, but Caron makes it clear that she only wants me, those sweet storybook nurses and the doctor in the room when it’s time to push the baby out. That gives me the task of kicking everybody else out of the room while maintaining peace.

5:35 p.m. The labor is starting to get the best of Caron. She’s physically exhausted, having been in pain for more than 20 hours, and after walking around, trying various positions, and eating 50 popsicles, they keep saying she still isn’t dilated enough. At this point, getting an epidural seems like the best option. Then the nurses check one last time and she’s ten centimeters.

“Go get my mother,” Caron says, and I run to the lobby, grab her mom, and we come right back to the delivery room.

5:50 p.m. I don’t know how science works, but we had been told that the doctor won’t be coming in until almost six, and maybe the baby is listening because that’s when she peeks her little head out.

Small dark curls peer into the world. My heart pounds. Everyone in the room scatters into their positions. Mine is to Caron’s left, and her mother on the right.

“Are you going to cut the cord?” the doctor asks me.

“Of course!”

The world stops and all I can do is tell Caron how amazing she is, how proud I am as she pushes, pushes, pushes, pushes, and then gives one more glorious push, bringing our baby into the word.

The baby is so tiny it’s scary — pale as soy milk, with noodles for arms, noodles for legs — and she’s speckled with fluid and not breathing.

I check Caron to make sure she’s still breathing and she is. The doctor calls our baby beautiful, hands me the scissors and tells me where to cut. Is she alive? I snip and they take the baby to the other side of the room to examine her. I followed.

She looks even smaller here, and she’s still pale. But this time her eyes open, and then she winks at me and lets out a small scream. For the first time in a really long time, I cry. I cry for her, I cry for Caron, I cry for our family, our pain, or journey, the times we thought we wouldn’t make it, the fear of this very moment, and for the moment itself.

And Caron cries as she holds her baby for the first time. She did it — 22 hours of love, labor, prayer, music and good people.

Cross Ashlyn Watkins — five pounds and one ounce, 18.5 inches — comes into the world on January 15, 2020, at 5:50 p.m.

I post a pic to my Instagram story and Dee Dave is the first to call and congratulate me. “Welcome to the club of fatherhood!”

* * *

At home, my family was ready to be good and settled. We were stocked with snacks and fresh pillows for my wife and everything a new baby could possibly need. But when it comes time to slide by Dee Dave’s freestyle event, I call him and tell him I’m not going to make it tonight. I’m not ready to be away from Caron and Cross yet. It’s only been eight days since her birth. I’ll catch the next one, I say.

“No worries, bro. Enjoy the baby,” he says. “I’m headed to Atlanta for a show tomorrow, so I’ll catch you next time.”

“OK, bet!” I said, “Next time.”

There is no next time. Dee Dave hosts an amazing event and is gunned down the next morning on his way to the airport, where he planned to fly to Atlanta to perform. It was a case of mistaken identity.

“Freedom or jail, clips inserted, a baby’s being born

Same time my man is murdered — the beginning and end”

I can’t help but think about how proud Dee Dave was of his own son. He worked so hard for him. And Dee Dave’s dad, a great man, loved his son dearly too. What happens now to his son, his dad? How do they move on? That clouds my thoughts as I hold my new daughter and look into her small eyes, praying that things will be better for her. Like Dee Dave said, I’m in that fatherhood club now.