Being a successful young professional today usually includes a cluster of events, mixers, panels and meeting on meetings that seem to never end . . . well, it was up until COVID happened. The pandemic swallowed all of our crazy schedules, making even the busiest workaholics learn to function from home. For me, the last few months were eye opening and a time to reflect on the things that really matter like love, family and community – and tune out the things that don’t.

Dartmouth College professor and award-winning poet Joshua Bennett, author of “The Sobbing School” and “Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man” captures the beauty of what really matters in life — the memories, youth sports, family traditions and little moments that many of us take for granted — in his new book of poems, “Owed,” which couldn’t have been more timely. I recently got a chance to talk with Bennett about his new book on an episode of “Salon Talks.”

Bennett and I unpack everything from what it’s like teaching college students during a pandemic to his writing playlist, to the tough questions around how Black writers feel about new enthusiasm for their work from white people. You can watch my “Salon Talks” episode with the Joshua Bennett here, or read a Q&A of our conversation below to hear more.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

How have you been handling COVID?

It’s been surreal, man. I got married.

Congratulations.

Thank you, thank you. I moved out of the city of Boston, I mourned my grandmother, and also had these new books that I actually dedicated to her come into the world. It’s just been this incredible spectrum, thinking about both life and death at this very large, world historical scale. But also, just in the intimate constraints in my own life, thinking about both my grandmother, but also this small new life with my son coming into the world. So, it’s been surreal.

When was your son born?

Well, he’s due in October. The whole process of my wife’s pregnancy, the ultrasounds, everything has taken place really over the past six, seven months.

Is this your first child?

Yes.

I just had my first child in January. And it’s crazy because we got married last year, but we were planning to have a wedding this year, and we just decided to bump it up. We were just thinking about all the people who are going through these COVID weddings, and just like the madness. Did you guys do that?

We did. Right outside here, man, at our new place. The COVID wedding is fascinating.

Has the isolation of COVID been good for your writing? Has being home been good for your writing?

Yeah, that’s a great question. I mean, I think it’s transformed my writing process. I’ve heard other writers say this. My reading rhythm is completely different. Nowadays it’s strange, because in some ways I was looking forward . . . because I’ve been off from teaching for the past couple of terms. I already was going to have this time off, but being in the midst of the pandemic and the midst of the move, it’s completely changed in some ways, my writing practice, as well.

If I had hours just to myself, you know, I’ll be moving through the poems. And I think it’s just pushed me in a different form. I finished a manuscript, for example, that’s a hybrid of poetry and fiction. I’m finishing up a manuscript that’s narrative non-fiction about the history of spoken word. And those books, I think, have really been inflected by the moment. They both include explicitly, narratives around COVID and thinking about the way this pandemic specifically, I think, has affected Black people in a way that I think has fallen out of the national conversation.

I’ve never been more disciplined throughout my whole career as a writer until this pandemic. I mean, everything is like clockwork to me, from designated writing time, to spending time with my wife and baby, to going for walks. I want it to end, but this production and how organized I’ve become is like, it’s crazy. It’s something that I didn’t imagine.

I do think there are lessons from it. There are always lessons from tragedy. This is again, one of the great gifts of the Black literary tradition and other traditions, right? Is that part of what I’ve learned is what matters to me the most, to be frank.

Talking about intimate time with loved ones, during the pandemic I’ve learned to put that first. I’ve been a very career-driven person since I was quite young, and I think this was the first time it was like, you know, I need to put some of this stuff away, spend time with my wife, get on a FaceTime with my father, with my mother, check in with my goddaughter. You know, these are moments of social life that the pandemic has helped me realize, maybe I was actually pushing them to the background. Even as I was foregrounding them in my work. Thinking about the book, on the cover, is me and my dad, but this pandemic made me think, “Well, how often am I really checking in with him?” So yeah, it’s changed my discipline, but I think in another way, as well.

As a teacher, do you think universities are handling COVID right? Or do you think they’re moving too fast? I’m teaching all online classes this semester, but I love being in a classroom. I need to be in front of my students. It’s part of the social experience for me — their reactions, their readings, the conversations. I’m not excited about starting school this week and being online. But at the same time, safety first. What do you think?

I think it’s a moment in which we have to question what is a university? And what are our highest aspirations for it? Most people in my family didn’t go to college. My mother growing up, was the only person I knew with a college degree. She studied accounting at a school nearby where she lived in the Bronx. At Dartmouth I’m teaching one class online. Some of it’s going to be asynchronous, so it’s not even clear to me how much actual individual teaching time I’m getting with my students.

It’s making me think about those other textured moments, like office hours. I do my office hours as walks around campus. So, you set a time with me, we go on a walk around campus. We talk about what we’re doing, what you’re up to, what questions you have about the course. And that falling out of the teaching experience has been so interesting to me, man.

You asked the question about how I think universities are handling it. The fact that it varies so widely has been really striking. There hasn’t been a kind of uniform – and that mirrors other aspects of how we’re dealing with COVID in this country. There’s no sort of clear federal response, and then universities like Cal State they’re like, “We’re not opening up for the fall.” And then you had other places that said, “Oh, of course, yeah, we’ll open.” And then, other places have a mix, right? With Dartmouth, I think for me, it was clear from the beginning. I have a baby coming into the world. My wife is pregnant. I’m not coming to campus. Even as a junior faculty member, it really made me think, what do you value? And how are you going to express that in a moment of great duress? But yeah, I miss my people.

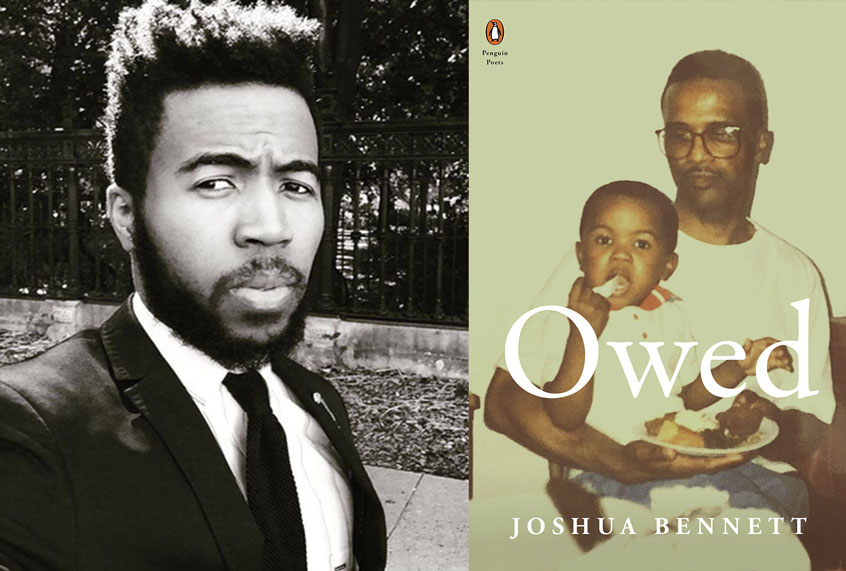

Let’s get into this amazing book, “Owed.” Talk to me about the cover.

Yeah, shout out to Mom Dukes. My mom took this photo, man, 28 years ago. It’s me and my dad at a party in the house. I’m eating cornbread, collard greens, chicken off his plate. I wanted to honor him. I wanted to honor our family. And when I think about my father, his life is like a textbook. Grew up in Jim Crow, Alabama. Fought in Vietnam. Came back to New York City. Lived with a bunch of his brothers in an apartment building, and met my mother in a house party.

I think a lot about how the way I learned to articulate history and literature is largely from seeing his experience. What I learned about what it meant to be Black came from him. I wanted to honor him on this cover. I think about “Owed” in a double sense, owed as in, these poems are celebration. But also, in aesthetics of reparation, right? As we’re in the midst of this national conversation, how do we think about the other forums that will need to accompany this sort of monetary debt as owed to Black people? How can art contribute to that?

For a lot of people watching this, this is going to be their introduction to you. Can you give us a glimpse into some of the energy behind the creation of this book? What were some of the things that you were feeling as you wrote it?

That’s a great question. What was I feeling? Honestly, I was thinking about . . . And I love some of your insights on this, brother. I was thinking about my first book, “The Sobbing School,” and the moment in 2015 where I was writing that book, largely thinking about Mike Brown and the spirit of grief and mourning and reflection. And I think with this book, trying to also make sure that I was honoring the celebration and the joy and the persistence and the tenacity of Black life.

At the core of this book, I wanted to think what are Black people doing when we’re not just resisting the forces that constrain us, right? I have poems in here about the 99-cent store. I have poems in here about growing up in a middle school where everybody wanted to be a hooper, so we were wearing ankle weights, right? Thinking about those tiny moments of the texture of Black social life that of course, we’re constrained by the police state. But you’re not always thinking about that, right? I think sometimes, the way we’re especially training young writers now to articulate Black life in public, it kind of doubles down on a critique that doesn’t always foreground the full texture of our lives. So, that’s the energy of this book.

I was thinking about church, I was thinking about hip-hop, I was thinking about growing up in Yonkers, you know, in the same neighborhood as Jadakiss and DMX and Mary J. Blige, shout-out, and Ella Fitzgerald. I was thinking about what that kind of literary tradition meant to me, as someone whose mom was from the South Bronx, my father was from Birmingham. I was from Yonkers and what did that mean? This book is also like everything I write, it’s about Yonkers, New York. And it’s about people trying to make a name for themselves. And it’s about, as Gwendolyn Brooks says, you know, their country’s a nation on no map. You know, this is for those people who have never really felt like they have a home here in America, as it’s often advertised.

Every time I read something about ankle weights, I get upset because I think about how I tore my knees up.

Oh, man.

Kids, don’t do it.

It’s not prescribed.

I’m pretty sure Vince Carter never, ever played with ankle weights on concrete. God gave Vince and LeBron and Mike, that’s from God. That’s not from wearing ankle weights on concrete. It doesn’t work like that.

That’s facts. It goes back to discipline. I mean, I loved what you said about discipline in the beginning. Because that’s part of what I’m trying to think about in the book. Like, what are these other forms of discipline that we hone? That 99-cent store poem is also about just growing up. You couldn’t always get the name brand cereal in the supermarket. That’s a form of discipline – like, boy, don’t even reach for those Frosted Flakes. Or like when you’re eight, and you don’t have McDonald’s money. I wanted to celebrate all of that. That’s really the heart of it.

As Black writers, I feel like our stories and our experiences like what you went through in Yonkers versus what I went through in Baltimore, versus what some brothers and sisters are going through in Atlanta, or Compton, or wherever, we all have these interesting stories.

In our current political climate with the constant killing of unarmed Black people, the oppression and the wild racist in the White House, all of these crazy things that are going on have a whole lot of people wanting to connect with us more and understand our stories, and understand our narratives. And sometimes, I’m torn because I think good writing is good writing. Since I became a reader, I’ve been trying to learn about different experiences. But now, a lot of people who are trying to learn about these different Black experiences are only doing it as a reaction to what’s happening in the world. They don’t want to be the person who’s like the racist. Are you okay with that type of attention?

You’re asking the real questions. I mean, it’s strange to me because the relationship is still extractive in some sense, right? I say this as someone that lived for a while in a pretty liberal part of Boston where there are Black Lives Matter signs everywhere, but you’re looking at me wild when I walk down the street.

Crazy, right?

I’m just like, you people are actively, persistently racist, and you have all these books. You have Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book, you have the Black Lives Matter sign, and you would never send your kid to a school with Black people, ever. You would actively avoid social spaces with Black people at all costs, right? And so to me, part of what’s so complicated is, there’s a way to adorn oneself in all the trappings of loving Black people, while actually knowing no Black people, having no meaningful engagement with the things Black people have written.

I love how you started with writing. Because you actually talk to some of these folks, and this again, across the spectrum of race and ethnicity, that actually have no engagement with Audre Lorde’s oeuvre, right, as a writer. They’ll rattle her name off, maybe, and maybe they’ll talk about bell hooks. They probably won’t talk about June Jordan. But if they do, say, “Well, have you actually read the substances of what these people are saying? Because they had a critique of a lot of things you love. And they have a critique of the thing you’re doing right now.” So yeah, I don’t love it, man. The idea that Blackness and Black culture is just a site of extraction, is something I think we need to refute at every turn.

Now, do I think this can be a moment where Black institutions, Black writers, Black thinkers, Black studies, practitioners, can get what they’re owed? Of course. I think that’s where we need to put the pressure. It’s like okay, you care about Blackness, Black culture so much, you need to fund Black students’ projects. You need to fund Black cultural centers, Black community centers, Black communities. We need reparations. We need to actively have investments in our people.

Yes, something real. I’m good if you don’t have a sign in your lawn. And I’m also good if you don’t paint Black Lives Matter across the beltway. I mean, it’s cute, but it’s the same thing to as me tweeting, “I care about the kids,” and then just walking past a bunch of starving kids. If you really care, then what are you actively doing to support these ideas that you have versus just the chatter?

Another thing that I thought about while reading “Owed” was just the lyrical bounce to it. I was wondering, “Who is on his playlist?” When you work on different books, do you have different playlists? What sort of songs did you have going through your head while you were putting this together?

I always have Kendrick on and Tramaine Hawkins. Always for me it’s going to be a mix of gospel, hip hop, and R&B. Mint Condition. I always got swing on, in part because that’s my aesthetic, right? I love that you said bounce, because “You Send Me Swingin'” is maybe my favorite R&B song ever. I want the work to swing, so I’m always listening to Mint Condition, Boyz II Men, Whitney, of course. I was listening to this Whitney Houston clip from the “Arsenio Hall Show” where she’s just singing a hymn just off the top of the dome. And I was like, “That’s what I want.” And Sylvia Wynter, my favorite living writer said this; she wanted her work to sound like what it sounds like when Aretha Franklin sings. So, always got Aretha on in the background. Mick Jenkins is a young cat who I think he’s incredibly talented. Love his work. Who else am I listening to? Biggie, of course. Jada, and X.

You definitely got to throw a homie in there.

Yeah, yeah. But I think about X too because I grew up in sort of like a Black Christian family where the theology was very, very heavy. And so for me, DMX helped me marry the sacred and the profane in a way that was so liberating, man. And he also loved animals. So, my first book that came out this year was about the relationship between Black writers and animals. And the way I saw DMX talk about dogs was so fascinating, in part because I think in the United States, we have a very sort of public bourgeois culture around dogs where people talk about dogs as their family members, et cetera.

I’d love to hear about how this looks in Baltimore. In south Yonkers, a dog is not your child. But a dog has value. Like, you don’t disrespect your dog, but a dog is not part of your family. A dog is its own individual. It’s opaque. Dogs attack people. It’s like, you have a kind of unwieldy relationship with this thing, because you recognize its power. And I think DMX talks about that on “Grand Champ.” He says, you know, “I trust dogs more than I trust humans.” And there’s something there that I think is so Black and complicated. His name means Dark Man X. So, I always have Earl in the back of my mind.

Down in Baltimore, people do love their dogs more than anything. I mean, it’s crazy, because like, the first dude who really, really, really introduced me to just pit bull everything, pit bull culture was a dude from Yonkers who moved down to Baltimore. His name was Aaron. He was an older dude, and his dog was kind of like his child. And then, one of my friends, they got a job walking his dog. We were maybe like, 10 years younger than this guy. He got a job walking his dog, and we ended up calling him Dog Boy because he walked the dogs all the time. I feel like it’s strong in New York, but it almost seems like it goes to a different level down South. That’s why I think that one of the reasons why “Salvage The Bones” was so powerful because it hits you. It’s a special relationship. I’m not chasing no dogs around.

It’s hectic. Trust me, I got myself Apollo back here. I mean, it’s hectic, man. And people ask me where his name is from, and I’m like, there’s the Greek version, but it’s also the Apollo Theater and Apollo Creed, right? You see the dog as part of a Black family.

Performance is such a big piece about dropping a new book, of being a poet, of being a writer. You want to get out and you want to share your work. Do you have any plans on doing online readings just to promote the book or to connect with people who have been reading it?

Yeah, for sure. I’ve got a reading coming up with Rachel Eliza Griffiths at the Midtown Scholar Book Store.

Is that in Harrisburg?

Yeah.

That’s one of my favorite book stores. It’s so beautiful.

I read there live for one of my first poetry book drops. And it was packed.

They’ve got a great community. I love that store.

It’s beautiful. One of the best readings I’ve ever had in my life. So, I got a reading there with Rachel Eliza Griffiths. I have an event next month with Imani Perry, who is also my dissertation advisor at Princeton. We’ll be talking about both “Owed,” and also my book of criticisms. I miss the in-person stuff of course because I built my career like that. You know, doing spoken word videos on YouTube. Like, there’s stuff from me when I was 17 years old that’s out there.

Poetry slam was my introduction to it. I mean, it’s funny, I don’t really talk about this a lot in interviews or in public conversations, but I’m a self-taught poet. I didn’t go to an MFA program. I learned through poetry slams and doing spoken word shows. That was my introduction to “literary poetry.” Then, I did the Calgary Creative Writing Workshop. I did Cave Canem It really was all of these historically Black institutions that trained me to think about what it meant to write on the page. I’m classically trained as a literary critic, like I’m PhD in English from Princeton. But when it comes to the poems, I have a completely different project in a certain way, just where it comes from. I’m interested to see what happens to the future of performance, to see a great turn because this distance between us that’s mediated by a screen, it completely changes what a performance is and what it can be.

It does. You do a Zoom in front of like, 200 people, and everybody’s muted, so you can’t hear reactions.

Yeah, especially when energy drives you. Like, if you’re the kind of reader where a snap or a clap or an amen takes you to another level, that’s actually really complicated, what happens when that’s gone?

As a writer, how has it been making the switch to narrative non-fiction from poetry?

Tough. Not going to lie. I try not to lean too much into genre distinction, but I think writing a book of narrative non-fiction is very different from writing a book of poetry. And is different from writing a work of literary criticism, but I think it’s been useful. I didn’t know what genre was when I was five. But I knew a preacher was telling a story, and my grandma was telling a story. And I liked when my mom told stories. And I wanted to find a way to do that with this thing called poetry. And I think narrative non-fiction is bringing me back to that initial impulse in a new and interesting way.

Can you give any advice to new poets on the come up? A lot of people who watch our videos and watch some of the interviews that I do are aspiring writers. They’re up and coming, they’re in their prime. Sometimes, they feel like they want to quit. Sometimes they feel like their work isn’t resonating the way it should. You’ve had tremendous success. Can you give them some knowledge and some things they can walk away with?

Read everything. Read as much as possible. I think sometimes, when you’re not writing, you need to be living. Sometimes when the poems aren’t flowing you actually just need to go outside. And I know the places you can go outside are quite limited right now. But you might just need to go get a breath of fresh air, sit under a tree. Don’t locate your human value on the page.

As someone that came out of a writers’ community where we were all very young, we were making videos, we were touring the world. We were going to Botswana and South Africa and India and U.K. What I wish someone would have told me at that moment, even as I had real, incredible visibility, was that I needed to make sure I was grounding myself in human relationships that had nothing to do with my success as a writer. And I think that’s the most important advice I can give a young writer. Your value should not be located in this craft.

I’ve tried to locate my practice now in the love of people. There are ideas I want to get out. There are people and communities I want to see celebrated in a world that denigrates them. But I do not locate my value as a person on what my books do, or how good my poems or prose are. It’s just not interesting to me anymore, and I think that’s important especially when you’re teaching young people.