Perhaps the old saying “we’re better together” applies to the inner workings of the universe, too. On October 1, astronomers announced they found a giant black hole surrounded by protogalaxies that date back to the early universe—as in, when it was less than one billion years old.

The discovery was made with help from the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope; the findings were published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

It’s the first time a close grouping has been observed so soon after the Big Bang. Astronomers hope that this discovery will help us better understand how supermassive black holes formed and grew so big and so quickly. In a statement by the ESO, astronomers say this discovery supports the theory that black holes grow quickly within web-like structures. According to this theory, it’s because they need plenty of gas to fuel them.

“This research was mainly driven by the desire to understand some of the most challenging astronomical objects — supermassive black holes in the early Universe,” Marco Mignoli, an astronomer at the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) in Bologna, Italy, and lead author of the new research published today in Astronomy & Astrophysics, said in a statement. “These are extreme systems and to date we have had no good explanation for their existence.”

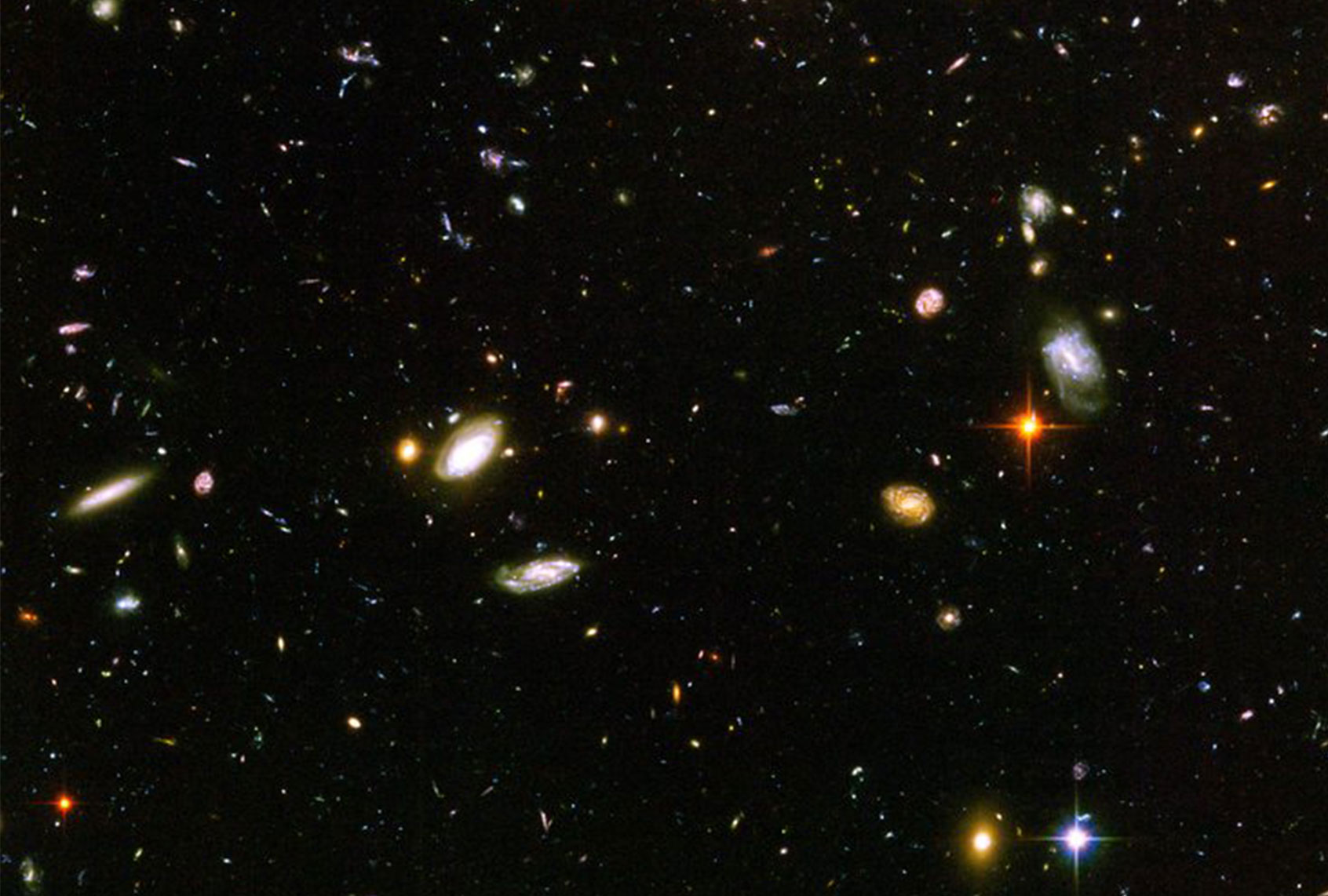

The new observations reveal that there are several galaxies surrounding a supermassive black hole lying in a cosmic web in which gas extends to an area over 300 times the width of the Milky Way galaxy.

“The cosmic web filaments are like spider’s web threads,” Mignoli explained. “The galaxies stand and grow where the filaments cross, and streams of gas — available to fuel both the galaxies and the central supermassive black hole — can flow along the filaments.”

The light from this cosmic spider web has traveled to us from a time when the universe was 0.9 billion years old. (For comparison, the universe is currently 13.77 billion years old.)

“Our work has placed an important piece in the largely incomplete puzzle that is the formation and growth of such extreme, yet relatively abundant, objects so quickly after the Big Bang,” co-author Roberto Gilli, also an astronomer at INAF in Bologna, said in a statement.

Astronomers believe that the very first black holes grew very fast, to reach masses of a billion suns with the first 0.9 billion years of the Universe’s life. However, astronomers have long struggled to explain how these large quantities of fuel helped these black holes grow so fast, in such enormous sizes, in such a short amount of time, by the universe’s standards. Astronomers now think the cosmic “spider’s web” and the galaxies within it contain enough gas to provide the fuel that a black hole needs to grow enormously so quickly. How these web-like structures first formed remains a mystery, but scientists suspect that massive dark matter halos are key to better understanding.

“Our finding lends support to the idea that the most distant and massive black holes form and grow within massive dark matter halos in large-scale structures, and that the absence of earlier detections of such structures was likely due to observational limitations,” Colin Norman of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, also a co-author on the study, said in a statement.

These galaxies are some of the faintest that have been observed by current telescopes, leading astronomers to believe there is so much more to be discovered.

“We believe we have just seen the tip of the iceberg, and that the few galaxies discovered so far around this supermassive black hole are only the brightest ones,” co-author Barbara Balmaverde, an astronomer at INAF in Torino, Italy, said in a statement.

Avi Loeb, chair of Harvard’s astronomy department, told Salon via email that the concentration of galaxies are “in the neighborhood of a luminous quasar when the universe was about a billion years old.”

“The bright quasar is fueled by the infall of gas onto a massive black hole, weighing over a billion Suns,” Loeb told Salon. “Finding such a monster black hole is similar to seeing a giant baby, the size of an adult, in a delivery room; the only way it can form so early is inside a galaxy more massive than the Milky Way, which feeds it with a huge amount of cold gas.”

Loeb added “such galaxies are extremely rare in the early universe and can only be assembled in the densest environments where objects condense much earlier than in the rest of the Universe.”

“As a result, one expects the environment of the quasar to be denser than average with a concentration of additional galaxies,” Loeb said. “And this is exactly what Mignoli’s team found.”