Thanks to large tax incentives, the “Camera Ready” state of Georgia has become the go-to place for film and television production in recent years. Such production has proven financially significant for the state, with an estimated $9.5 billion impact in 2017. Advertising that “Georgia is Every Location,” the state offers filmmakers a diverse array of landscapes, settings, and moods at an affordable cost. While Atlanta has received a great deal of attention from producers, smaller towns have also become the sites for a number of highly successful television series. Jackson stands in as Hawkins, Indiana in the Netflix series “Stranger Things”; Senoia is home to “The Walking Dead”; and Covington, “The Hollywood of the South,” sets the scene for “In the Heat of the Night,” “The Vampire Diaries” and “Sweet Magnolias,” among others.

Covington has been the setting for many films and television series set in the South—Sevierville, Tennessee, and the Great Smoky Mountains in Dolly Parton’s Coat of Many Colors and Dolly Parton’s “Christmas of Many Colors: Circle of Love”; Hazzard County, Georgia, in the original “Dukes of Hazzard”; a small Texas town in “Dumplin'”; Serenity, South Carolina in “Sweet Magnolias.” As the Newton County Chamber of Commerce website promotes, Covington has become a “mecca” for production as it is “easily transformed into a Civil War village, a 1950s town or a modern-day city.” But there is more to production companies’ frequent return to the town than low cost, the convenience of Atlanta, and a known work force. Covington offers a familiar, clichéd backdrop for representing a white South on screen that continues to appeal to many viewers.

On screen, this real-life-town-as-fictional-set confirms and reinforces over a century’s worth of popular conceptions of “the South” as pastoral and white. While literature, films, and scholarly works have challenged these notions time and time again, directors and producers nevertheless continue to resurrect and re-present a monolithic cinematic representation of a South. The imposing courthouse on the town square (where historically, justice has not always prevailed); the idyllic square itself where characters meet next to and in the shadow of a 1906 Confederate monument that has been the recent focus of local debate; the pastoral Covington cemetery, part of which is dedicated to Confederate veterans; the several local white-columned buildings; the list goes on.

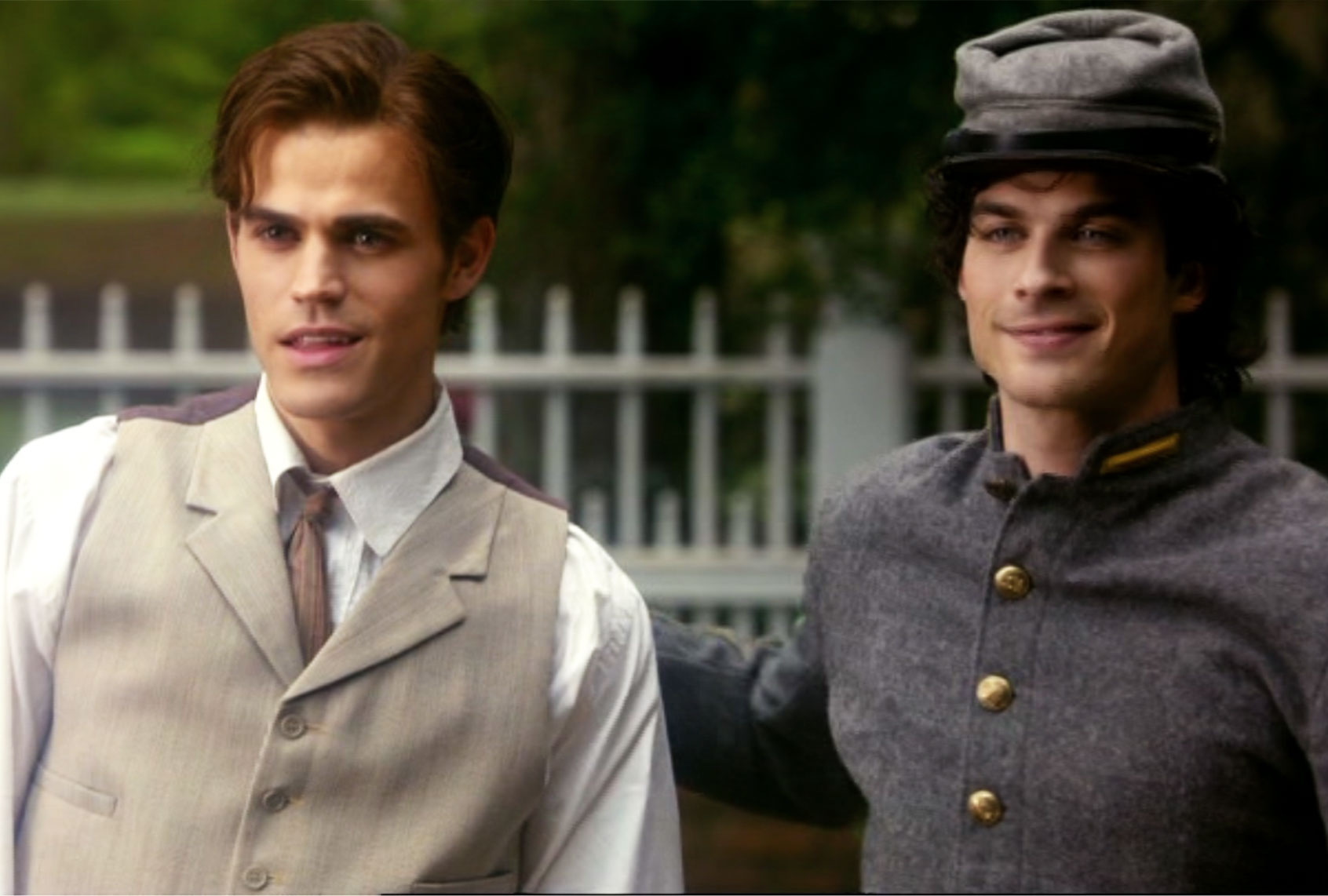

Additionally, many of the shows and films center primarily on white characters. There is one character of color on “Vampire Diaries”—Bonnie, a witch—out of 10 principal characters. “Sweet Magnolias” features an African American character named Helen Decatur (Heather Headley) as one of the three female leads, although her storyline is significantly underdeveloped compared to that of her white best friends. Despite such inclusion and despite a nod here or there to racial tensions in the past, these shows confirm and perpetuate romanticized, outdated notions of the South as white, genteel and unified (with the exception of relationship or supernatural conflicts). One might counter that we should not expect more from romantic television dramas, designed for entertainment and escapism, but why shouldn’t we expect more in 2021, in the era of Black Lives Matter, and in the wake of an attack on the U.S. Capitol? In reinforcing the pastoral and dominant whiteness of the small-town South and in relying on century-old tropes, such entertainment obscures the reality of what is happening on the ground in the South today—a movement on multiple fronts and by multiple players to challenge white political dominance.

Covington itself has been the actual site of racialized power struggles in recent years. In August and September 2016, protests against the construction of a proposed mosque took place on the Covington square. After leaders of the Doraville-based Masjid At-Taqwa acquired land in Covington, Newton County Commissioners passed a temporary moratorium on permits for houses of worship. The moratorium eventually expired, but not before hours of public hearings made it quite clear how many county residents felt about the possibility of a new mosque in their area. Though initial reasons given for opposition focused on concerns regarding increased traffic, comments at the hearings and on social media, along with the protestors’ oral and visual rhetoric, revealed that there was more to it than that. The Economist reported that speakers”after declaring that they were in no way prejudiced…predicted that Covington—a picturesque town, often used by filmmakers, in a pretty county of around 100,000 people—was set to become a hell of violence and jihad, in which their families would no longer be safe.”

It has not stopped there. Removal of the Confederate statue at the center of the square, which the Newton County Board of Commissioners voted 3-2 to pursue in July 2020, continues to be debated in court with a hearing set within the Georgia Court of Appeals for April. When Newton County public schools remained closed after the winter holidays due to concerns about high Covid infection rates, comments on school Facebook pages reflected deep political divisions within the town regarding mask wearing and “choice.” Though Newton went blue in recent elections, the county is clearly divided between red and blue— Rep. Jody Hice (R) on one side and Rep. Hank Johnson (D) on the other—with neighboring counties that are certainly more red than blue.

Ultimately, the purple prose of popular television ignores such stark political division and such struggle, opting instead for replicating a trite white South of moonlight and (sweet) magnolias. What if Covington were to be used instead in service of furthering anti-racism, educating and reminding viewers—as Selma, partially shot in Covington, does—of the civil rights movement that continues to take place on southern soil and in southern courthouses? Covington could set the scene to complicate the notion of “the” or “a” South that has held sway in filmmakers’ and viewers’ imaginations for so long. Perhaps then the cinematic specters of an imagined white South could finally be laid to rest.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified Congressmen Jody Hice and Hank Johnson as Georgia State Representatives, not U.S. Representatives from Georgia. The story has been corrected.