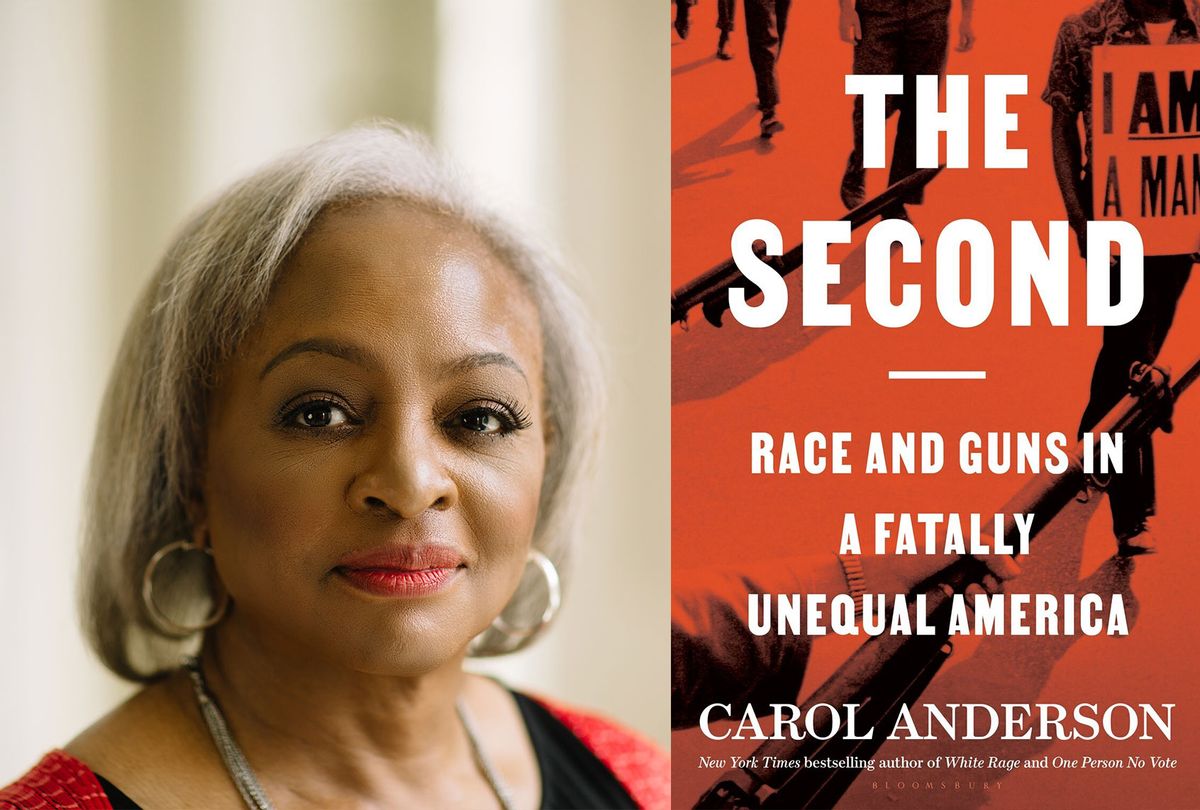

Carol Anderson is likely to trigger a lot of people on the right with her book about the anti-Black history of the Second Amendment, "The Second: Race and Guns in a Fatally Unequal America." But if anyone understands what white backlash looks and feels like it's Anderson, who also wrote the 2016 bestseller "White Rage."

In her new book, Anderson, the chair of African American studies at Emory University, shares a history of the Second Amendment that few of us ever heard, arguing that it was included in the U.S. Constitution after demands by slave states for a constitutional right to form militias to put down slave revolts. Anderson details how Virginia's Patrick Henry and George Mason expressed fears that the federal government would not help them defeat slave uprisings, and demanded that the Second Amendment be included so they could deal with such revolts themselves — an acute concern in the slave-owning oligarchy of that time.

From there, Anderson traces how for decades the Second Amendment only protected the right of white Americans to own guns. In fact, states like Virginia enacted laws in the early 1800's making it a crime for free Black people to carry guns. In the infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision, where the Supreme Court ruled that Black people were not citizens, Chief Justice Roger Taney — who wrote the opinion — expressed the concern that if Blacks were to become citizens, they would have the constitutional right to firearms

Anderson draws a straight line from the racist history of the Second Amendment and its application to our society today where armed (and unarmed) Black Americans are treated vastly different by the police than armed and dangerous white people. She points to the contrast between the case of 12-year-old Tamir Rice, who in 2014 was killed by police while playing with a toy pellet gun, andwhite supremacist Dylann Roof, who in 2015 murdered nine Black worshipers at a historic church in South Carolina, but was captured alive by police.

My recent conversation with Anderson for Salon Talks will challenge the preconceptions of most readers or viewers — and anger others. She wouldn't have it any other way. The transcript that follows has been edited for length and clarity.

I want to start out with something you talk about in your book that I've never heard — and I'm a lawyer — the history behind the Second Amendment, how and why it was really written. So tell us a little bit about that, because no one really knows about this, except for you and a few other really well-informed people.

So the key here is anti-Blackness. The key for the Second Amendment is the ability to have a militia to control Black people, to stop slave revolts and to keep Black people subjugated. It was part of the deal that was cut that allowed the South to be able to sign on to the Constitution. They needed to be protected. And I talk about these deals a lot, with the three-fifths clause, the extension of 20 years for the Atlantic slave trade, the fugitive slave clause, which were put in the Constitution because the South demanded that kind of protection in order to sign on.

But it was at the ratification convention in Virginia, where Patrick Henry and George Mason go toe to toe with James Madison. Because Madison had put control of the militia under the federal government because the militias had been basically unreliable during the war, and it was seen as a need to provide some standardization. Patrick Henry was like, "No. No. In that federal government, you've got people from Pennsylvania, people from Massachusetts. You know the North detests slavery. We can't trust that when there's a slave revolt, they will send the militia down to protect us." George Mason said, "We will be left defenseless." And so they put enormous pressure on James Madison, that if he wanted to have this Constitution and this government that he had crafted, they were going to need a Bill of Rights, and that Bill of Rights was going to have to include protection for slavery. That's the Second Amendment.

What was going on that would make them so keenly concerned about slave revolts?

So we had a series of revolts starting in the 1600. And there was a huge revolt in 1739 in Stono, South Carolina. It was the Stono Rebellion. Sixty people were killed, including 20 whites. And in this rebellion, you had Black men who had been on a road labor gang, who were spotting, surveilling the rotating of the guards, how deep and where the arms were. On a Sunday, when there weren't a lot of white folk around, they struck. They killed the two people who were at the depot where the arms were, they took the weapons and they set off for Florida to freedom. The law said that every white man had to carry a gun. And so the white men who were in church, the alarms go off, they pick up their guns and they go running after the folks at Stono, hunting them down and catching them, and then using torture and all kinds of brutality to send the signal, do not revolt. It was the largest revolt in colonial North America. That scared the bejeebers out of them.

In your view from studying this, the primary reason for the Second Amendment was anti-Blackness. Iit was the fear of these white plantation owners not having an armed group to protect them from slave revolts?

Yeah. That is the primary concern. It's not to say there aren't tangential ones. But that's the primary concern. One of the other major concerns they had were the use of the militia to remove indigenous people off their lands. And so you've got racism just coursing through the Second Amendment. So when you get this heroic language about the militia as the defender of democracy, remember that this was the militia that was driving George Washington crazy during the war because sometimes they'd show up and sometimes they wouldn't. Sometimes they'd fight, sometimes they'd run. And this was also during Shay's Rebellion, which was right before the Constitutional Convention, where you had white men attacking the Massachusetts government over taxation policy and land foreclosure and the militia refused to hop in there and fight. Instead, some of the militia were joining them in this battle.

In Boston, merchants had to hire a mercenary army, basically, to put down Shay's Rebellion. So this thing about protection of government, none of that was resonating with the folks who were drafting this at the time. Protection of government, a well-regulated militia to defend against foreign invasion? No. What it could do was put down slave revolts.

Anti-Blackness was so strong that during the Revolutionary War in South Carolina, they didn't even want to arm Black people to fight for their freedom. It seemed like the white slaveowners would prefer living under British rule than having their own nation if it meant giving arms to Black people.

Yes. So, after the war had stiffened in the North, the British decided to hit what they called the "soft underbelly" in the South. So, they took Savannah like that and were headed up to Charleston. John Lawrence, who was an emissary of George Washington, runs down to South Carolina and he's pleading with that South Carolina government: "You only have 750 white men that can fight. Everybody else has been used for the militia to keep that large Black population down. The British are bringing 8,000 troops. You've got 750. This is David and Goliath. This is a slaughter. You've got to arm the enslaved."

They said, "We are horrified that you would even ask us that. And we're wondering whether this is a nation even worth fighting for." They were willing to take their chances with the British, with the king, than arm the enslaved. I mean, that is how entrenched this was. Nathanael Greene, who was one of George Washington's generals, came down there, pleading with them, and he finally said to Washington, "They have a dreaded fear of armed Blacks."

Anti-Blackness resulted in laws in state after state that prohibited Black people from owning guns. Including free Black people, who were presumably citizens and the Second Amendment said they could.

You see these laws throughout the United States. As the U.S. is growing, these laws continue to come through. In Maryland, free Blacks were called a dangerous population. And so they could not have access to guns. In Virginia, free Blacks had to get a license renewed all the time, something that white men did not have to do. That was part and parcel of an array of laws to constrict the movement of Black people. They couldn't be mail carriers. You had laws where they couldn't cross state lines, or they had to pay a fee in order to be in a state for more than three days. You had all these kinds of restrictions on free Blacks because, again, this in-depth anti-Blackness is just coursing through the laws.

In 1857, there was the infamous Dred Scott decision. Guns come up here too, but remind people what Dred Scott stood for, and then how guns were actually part of Chief Justice Taney's opinion?

So what happened was, Dred Scott was an enslaved man whose owners had taken him to free soil, in Wisconsin and Illinois. And then they took him to Missouri, a slave state. He argued that because he had been on free soil, he was actually free. Well, Justice Taney was like, "No son. No son. No son." He's like, Black people weren't citizens at the founding of this nation. They weren't citizens. They could never get a passport because they weren't citizens. They couldn't carry the mail because they weren't citizens. And if they were citizens, they'd be able to go across state lines easily and carry weapons whenever and wherever they wanted. Remember that a Black man has no rights that a white man is bound to respect.

In your book, there are numerous examples of free Black people who were protecting their communities, being gunned down by whites. It's not just Tulsa, which everyone now knows about. They didn't know about. But there's also Colfax, Wilmington, Brownsville — the list goes on and on. Share a little so people understand, because we can't go through them all. But what was happening here? Was it that if Blacks did get guns when they were legally allowed to have them, white people were triggered right to the point of actually slaughtering them?

Black people with guns became the ultimate threat. I'm going to go a little bit before the Civil War, to Cincinnati in 1841. Here you had whites storming into the Black community seeking to do a full-boar slaughter because, ostensibly, a Black man had molested a white woman. Black folks were armed and they shot back, repelled the mob. The mob came back again. Black folks shot back. The white mob got so angry they got a cannon. They brought a cannon to a gunfight. And when they brought the cannon, then the police swooped in. And what the police did was not to arrest the white people who brought the cannon and were trying to kill all of these Black people. Instead, they arrested the Black folks in the city, and disarmed the Black community, thinking that if they took the weapons away from Black people, that would calm white folks down. Instead, it was like an invitation to the kill. And that's what happened in Cincinnati in 1841.

We have Elaine, Arkansas, in 1919. You had Black sharecroppers whose wages had been stolen from them. Imagine you work for a year expecting to get paid, and you get nothing. So they began to organize a union. Well, when the wealthy whites found out that they were organizing a union, they sent a surveillance party up there to bust up and shoot up the meeting. But the Black folks had guards outside that meeting, and there was an exchange of gunfire. A white man was killed and a white man was wounded. When the white townfolk found out about this, the mob came into that Black community. They were even coming in from Mississippi because this was written up as a Black insurgency, that Black people were just trying to kill all of the white folks in Elaine.

When Black folks are running away from this mob, and they're shooting wildly, two more white men are killed. That was enough to send the message to the governor. He brought in the U.S. Army with machine guns that had been used in the war in France, and they began gunning down Black people. Up to 800 were killed in this slaughter. There was this joy about this killing. You can see it in the documents. And no white person was ever indicted for the slaughter. Instead, Black people were put on trial for killing whites. And they were tortured. It took the NAACP coming in there to get these folks off of death row and out of prison.

This is history that most people are not going to know about. The idea of the Second Amendment is, at its essence, for whites. And then you go through time, and get to the civil rights movement. You have the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act. But the Black Panthers in California, as you discuss, still wanted to defend their community, specifically from the police. Share a little bit about when the Black Panthers in California legally owned guns, and how the California legislature and the police responded?

So you had massive police brutality raining down on the Black community, and absolutely no accountability in that system. And so the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense is formed by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, and they decide to police the police. They knew the law. They knew the California code. They knew that they could open-carry, and they also knew the distance that they had to maintain from the police while the police were arresting Black folk. And the police did not like that. They did not like having these leathered up, armed up, braid-wearing, 'fro-wearing Black folks monitoring what they were doing.

And so the cops ran to Don Mulford, who was a state assemblyman, and said, "We need help. Every time we pull them over, the weapons they're carrying are legal. They are licensed weapons. We can't get them on anything. How do we make them illegal?" And Mulford is like, "I got this." With the help of the NRA, they wrote a law that banned the open carrying of weapons. And Ronald Reagan was like, "I'm eager to sign this legislation the moment it hits my desk." So you get what you often consider as the guardians of the Second Amendment eagerly writing gun control legislation to ban the Black Panthers from openly carrying arms.

Mulford said, "Oh, this isn't targeted at any group. I mean, this isn't racially targeted. Not at all." But when you look at the letters, it's like the Black Panthers are a problem. We've got to bring the Black Panthers under control. Not, how do we ensure that the police are not brutalizing the Black community? So the way that you frame an issue has a lot to do with what you see as the solution.

You take the book to the present day to the disparity in the treatment of armed white people, like Kyle Rittenhouse and Dylann Roof, who have literally killed people, versus unarmed Black people and how they're treated by police. What does that double standard say about America today?

I looked at how these so-called testaments to the Second Amendment — "stand your ground" laws, open carry and basically the right to self-defense — how those actually play out for the Black community. And the disparities were just stunning. "Stand your ground" expands the castle doctrine by saying anywhere where you have a right to be — it's not like you just have to be in your home and somebody invades your home — then you have the right to self-defense. You've got the right to stand your ground. What makes it so lethal is that it's like, if you perceive a threat, when Black is the default threat in American society. If I'm in the grocery store, if I'm in a parking lot, if I'm in the park, and I perceive a threat, then I have the right to use lethal force. We see that in terms of the data that shows that when somebody white kills somebody Black using "stand your ground," they are 10 times more likely than somebody Black killing somebody white to walk away with justifiable homicide.

I use the example of Trayvon Martin, where you have an unarmed Black teenager who's being stopped in a neighborhood by an armed guy who's like, there's something suspicious about him. So you got the armed guy with the gun killing an unarmed teenager who has Skittles and iced tea. He is found not guilty because he had a right to be fearful. If he was so afraid, why didn't he just stay in the car? As the 911 operator said, "Sir, you need not to be doing that." When she said, "Are you following him?" So the disparity is there.

The disparity in open carry, where I look at Tamir Rice, who's the 12-year-old child in Cleveland who was playing alone in a park. There's nobody in the park and Ohio is an open carry state. Granted, his toy gun doesn't have the orange tip on it, but again, it's an open carry state. As long as you're not pointing the weapon at anybody, threatening anybody, you can open carry. The police rolled up, and within two seconds they shot Tamir Rice. They said, "He was a threat. We were afraid. He was dangerous."

Then you take Kyle Rittenhouse, the 17-year-old white kid who crosses state lines with an illegally obtained AR-15, and the police in Kenosha, Wisconsin, welcome him. "Oh, we really appreciate that you guys are here." They offer him water on a hot night. He then goes and guns down three men, killing two of them, seriously wounding a third. He walks towards the police with his hands up as if to surrender. They don't even notice him because Kyle Rittenhouse, who has just gunned down three people, is not a threat. He goes all the way back home before they go, "Oh, this guy killed somebody. I guess we got to arrest him." And that disparity in what is a threat and not a threat is what is at the base of the Second Amendment.

Are there any prescriptions available to change this?

This is the work that this nation must do, and is consistently resistant to. That is to dismantle anti-Blackness as part of the operating code of this nation. And when I say "resistant to," think about the pushback we're getting right now, in terms of the teaching of history in our schools, where you can't talk about "divisive" things such as slavery, such as Jim Crow, such as the genocide of indigenous people, such as redlining. What? The refusal to engage with the role of anti-Blackness and racism in this society means we keep having these circular arguments, and keep having these same events happen over and over. And so one of the things that you can see from this book, although I go back to the 17th century, the access that African Americans have to their rights does not change fundamentally when it comes to the Second Amendment, from being enslaved to being free Black to being a denizen — which is that halfway land between enslaved and citizen — to being emancipated to Jim Crow Black to post-civil rights African American. The precarity of Black life is always there.

Shares