Congressional Democrats are eyeing a little-known constitutional mechanism to prevent former President Donald Trump from running for office again, citing his responsibility for the Jan. 6 Capitol riot and subsequent attacks on American democracy.

According to a new report in The Hill, at least a dozen Democratic lawmakers have been quietly speaking, both publicly and privately, about whether or not it would be possible to use Section 3 of the 14th Amendment to permanently ban Trump — or anyone else who participated in the planning or execution of the Jan. 6 Capitol attack — from seeking elected office in the future. The post-Civil War clause bars anyone who has engaged in “insurrection or rebellion” against the United States from seeking public office, and reads:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The theory gained credence in the days following the Capitol riot, but quickly fell by the wayside with the hope that Trump would eventually accept his election loss and disavow the violence of Jan. 6. With the one-year anniversary of the attacks now passed, and Trump’s false claims of a “stolen” election still at a fever pitch, it appears the idea is once again being discussed on Capitol Hill.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

“If anything, the idea has waxed and waned,” said Laurence Tribe, a constitutional expert at Harvard Law School who has spoken previously about the 14th Amendment. “I hear it being raised with considerable frequency these days both by media commentators and by members of Congress and their staffs, some of whom have sought my advice on how to implement Section 3.”

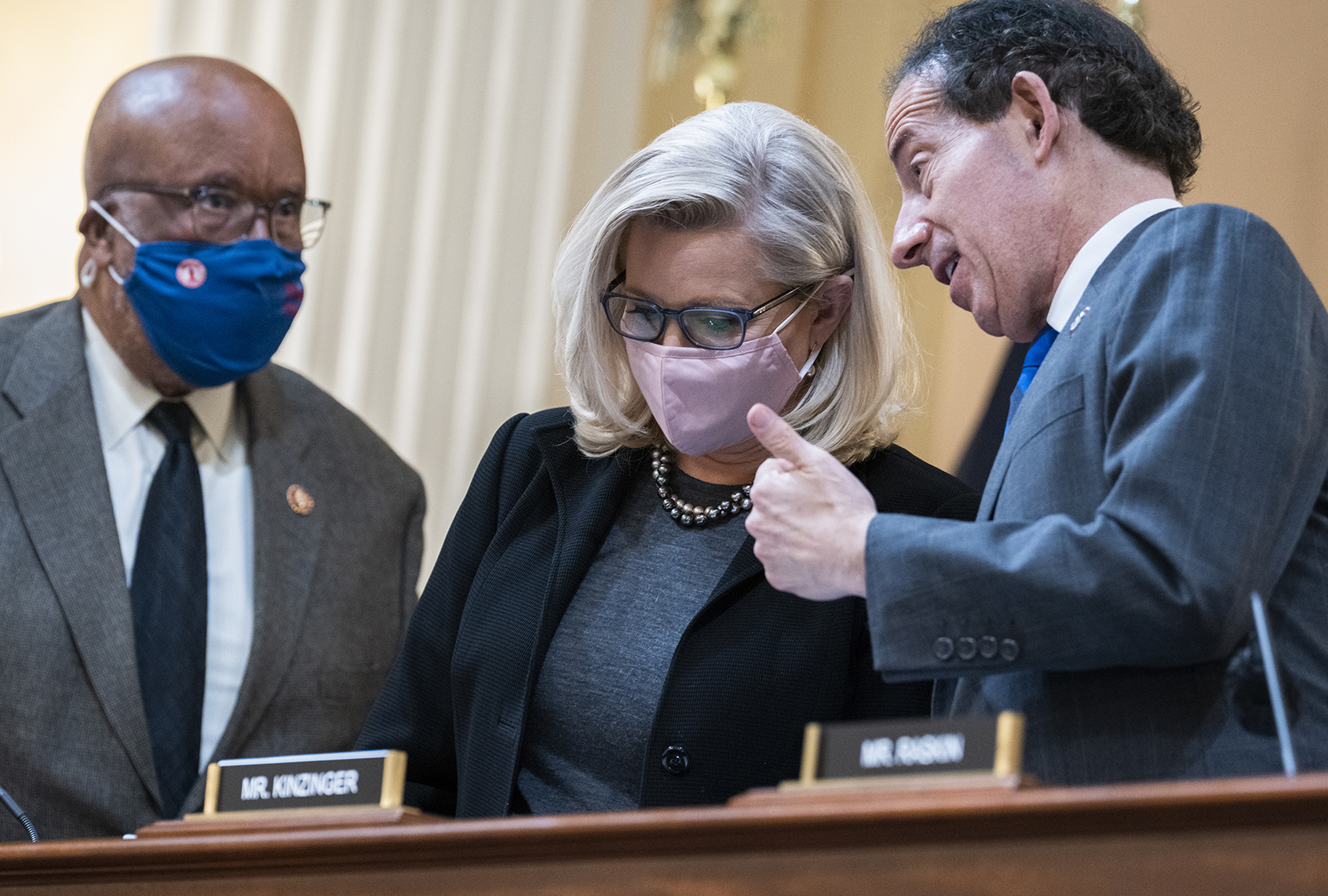

He shared with The Hill the names of several lawmakers who have reached out in recent weeks for counsel on gaming out exactly how such a controversial tactic might be used. Those include Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), a member of the House select committee investigating Jan. 6; Rep. Jerry Nadler, D-N.Y., chairman of the House Judiciary Committee; and Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., who told the outlet: “I continue to explore all legal paths to ensure that the people who tried to subvert our democracy are not in charge of it.”

Neither of the other two Democrats spoke with The Hill about their inquiries, though Raskin gave an interview last February in which he expressed his support for the premise.

RELATED: Laurence Tribe: If Garland doesn’t prosecute Trump, the rule of law is “out the window”

“The point is that the constitutional purpose is clear, to keep people exactly like Donald Trump and other traitors to the union from holding public office,” he told ABC News, adding that he planned to conduct “more research” on the matter before pursuing it.

It’s unclear exactly how the implementation of such a provision might work — it would likely be the first time in well over a century that Section 3 has been discussed in Congress, after the body waived enforcement of the clause for Confederate officials and some Ku Klux Klan members as a way to promote national unity during the Reconstruction era.

Constitutional scholars are split over how execution of the rule would work, with one group arguing that a simple majority vote in both chambers of Congress that found Trump guilty of fomenting the insurrection would be enough to bar him from holding future public office.

Others, including Tribe, say that a “neutral” fact-finding body would have to determine whether Trump officially engaged in an “insurrection” or “rebellion” — a task for either a Congressional panel or federal court.

RELATED: How Christian nationalism drove the insurrection: A religious history of Jan. 6

A separate stand-alone law proposed last year by Rep. Steve Cohen, D-Tenn., would give the U.S. Attorney General the power to argue that same case in front of a three-judge panel, though the bill itself has received little support thus far.

Liberal elections groups, such as “Free Speech For People,” have even been making the case that state-level election officials could use Section 3 on a state-by-state basis to take Trump’s name off their ballots if he were to run again in 2024.

All of these implementations would, however, face a major hurdle at the U.S. Supreme Court, which maintains a conservative majority after Trump appointed three justices to the bench during his four years in office.