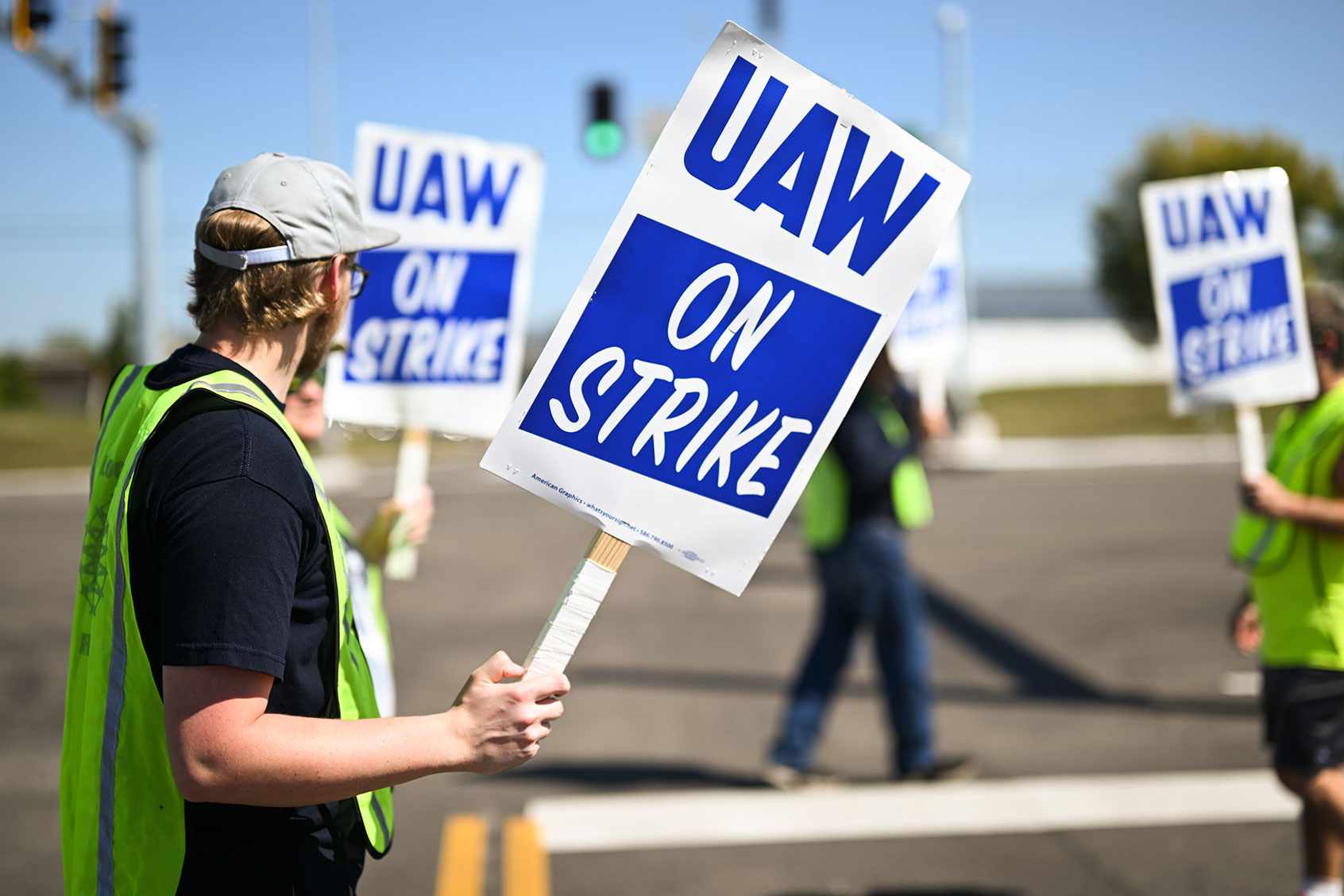

The United Auto Workers strike against America’s big three automakers is a high-stakes gambit that comes at a time when an increasing number of Americans support the union movement — but the percentage of workers who are actually union members is at an all-time low.

John Samuelsen is international president of the Transportation Workers Union, which represents 155,000 workers at airlines, railroads, transit agencies, universities, utilities and other service-sector employees. It’s the largest airline workers union in the country.

Samuelsen said in a phone interview that he saw the Teamsters’ recent UPS contract gains and the UAW strike as signs of a “potential paradigm shift, in a way that could represent a kind of great leap forward that could resonate across the trade union movement and for all working people.”

Just as Ronald Reagan “turned back the clock for the labor movement” more than 40 years ago “by firing all of the air traffic controllers,” Samuelsen said, “these two events can turn the clock forward.”

It was in August of 1981 that Reagan, himself the former president of the Screen Actors Guild, announced the mass firing of 11,345 striking union air traffic controllers and banned them for life from federal employment, after declaring that there would be “no negotiations and no amnesty.”

It’s hard to overstate what a kick in the teeth Reagan’s actions were for the labor movement, which was already suffering. Paradoxically, in the process of undermining unions the Great Communicator also captured a huge chunk of rank-and-file union households, a voting bloc Donald Trump capitalized on in 2016.

The American union movement had already declined from its zenith in 1945, when more than one-third of the nation’s workforce, buttressed by military production, was organized. By the early 1980s, that was down to one in five. Despite a major spike in strike and organizing activity, that proportion declined last year from 10.3 percent in 2021 to 10.1 percent, the lowest on record.

In the private sector, where the UAW is making its stand against the auto industry, just 6 percent of workers are in unions today, compared to the 33.1 percent organized in the public sector.

Despite a major spike in strike and organizing activity, the proportion of the nation’s workforce in unions declined last year to 10.1 percent, the lowest on record.

Reagan’s destruction of PATCO, the air traffic controllers’ union, was rewarded in opinion polls that showed the public, perhaps inconvenienced by the cancellation of 7,000 flights, sided with the president. One poll suggested that only 28 percent of the public thought the air traffic controllers should even have the right to strike.

That’s a universe away from polling today, which shows that 71 percent of Americans support labor unions, the highest approval level since 1965. All it took was decades of flat or declining wages, accompanied by a dramatic concentration of wealth at the top that created vast wealth inequality. That great upward shift came along with U.S. multinational corporations shifting their production offshore and, thanks to the U.S. tax code, shifting their tax burden onto American households.

Ironically, the issues that caused the PATCO strike almost a half-century ago have only gotten worse. Like today’s UAW under the leadership of Shawn Fain, the stressed-out controllers were looking for a four-day work week. They wanted a $10,000 raise, a better retirement package and an upgrade of the antiquated equipment that put the flying public at risk. At the time, annual salaries for those sensitive and crucial jobs were in the $20,000 to $50,000 range.

The New York Times recently found that the “nation’s air traffic control facilities are chronically understaffed” and that current “shortages are more severe and are leading to more dangerous situations than previously known.”

“As of May, only three of the 313 air traffic facilities nationwide had enough controllers to meet targets set by the F.A.A. and the union representing controllers,” the newspaper reported. “Many controllers are required to work six-day weeks and a schedule so fatiguing that multiple federal agencies have warned that it can impede controllers’ abilities to do their jobs properly.”

We need your help to stay independent

Decades ago the air traffic controllers were trying to do something about it and were punished.

“PATCO was also concerned about on-the-job stress for its members, as it reported 89 percent of those who left air traffic controller jobs in 1981 were either retiring early and seeking medical benefits or leaving the profession entirely,” according to Michael Barera, labor archivist at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Ironically enough, PATCO had endorsed Reagan in his 1980 presidential campaign. Less than a year later it became the first federal workforce union to be decertified by the Federal Labor Relations Authority.

As the role of organized labor declined, the power of capital and corporations ran the table in city halls, state capitals and on Capitol Hill, as both political parties fell into line with business interests that filled their campaign war chests. It was in the 1970s that the historic linkage between increased productivity and workers’ wages was severed, ensuring that only the owner class would see the wealth generated by technological advances.

“Starting in the late 1970s policy makers began dismantling all the policy bulwarks helping to ensure that typical workers’ wages grew with productivity,” wrote Josh Bivens and Ben Zipperer for the Economic Policy Institute in 2018. “Excess unemployment was tolerated to keep any chance of inflation in check. Raises in the federal minimum wage became smaller and rarer. Labor law failed to keep pace with growing employer hostility toward unions. Tax rates on top incomes were lowered. And anti-worker deregulatory pushes — from the deregulation of the trucking and airline industries to the retreat of anti-trust policy to the dismantling of financial regulations and more — succeeded again and again.”

From 1973 until 2016, the Economic Policy Institute reports, productivity increased by over 73 percent but actual hourly pay for workers only went up by 11 percent — that is, productivity grew more than six times faster than the wages earned by workers.

During COVID, a mass death event that killed 1.1 million Americans, including thousands upon thousands of essential workers, wealth concentration continued to accelerate here and around the world. In response to union organizing drives, major employers like Amazon and Starbucks dug in, regularly running afoul of U.S. labor law.

“The pandemic’s most significant outcome will be a worsening of inequality, both within the U.S. and between developed and developing countries,” wrote economist Joseph Stiglitz in Scientific American. “Global billionaire wealth grew by $4.4 trillion between 2020 and 2021, and at the same time more than 100 million people fell below the poverty line.”

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

During that same period there was a profound, almost existential re-evaluation of work by Americans. In 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 47.4 million Americans left their current jobs. To get a sense of the scale of this upheaval, consider the AFL-CIO, with its 57 constituent unions has a current enrollment of 12.5 million members.

Republicans in Washington, joined by Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., felt Washington had extended the safety net too widely during COVID and they blocked the extension of the Expanded Child Tax Credit, which in just six months had lifted millions of children out of poverty. Their agenda was transparent: Give capital more leverage against the working poor. It was time to crack the whip.

Their lash hit the mark: Childhood poverty skyrocketed from 5.2 percent in 2021, a record low, to 12.4 percent — almost a 140 percent increase in a single year.

And while Americans were increasingly coming back to full-time work, they were financially worse off for doing so, for two years running. “Real median household income fell by 2.3 percent from $76,330 in 2021 to $74,580 in 2022,” the Census Bureau reported. “Between 2021 and 2022, inflation rose 7.8 percent; this is the largest annual increase in the cost-of-living adjustment since 1981.”

The annual Federal Reserve analysis of what proportion of Americans could cover a $400 emergency expense “with cash or its equivalent” dropped from 68 percent in 2021 to 63 percent last year. For Black Americans, that number fell from 48 percent in 2021 to 43 percent. For Latinos, it was an even steeper drop off, going from 54 percent in 2021 to 47 percent.”

The saddest part of the American labor movement’s decline has been the role played by internal corruption. Just a few years ago, at least 15 UAW officials were convicted in a massive corruption scandal.

Perhaps the saddest part of the American labor movement’s decline has been the role that its internal corruption has played, to varying degrees. It’s impossible to grasp the full historical significance of the current UAW strike unless you know that just a few years ago a massive criminal corruption prosecution resulted in at least 15 felony convictions of national and regional union officials.

As it turned out, UAW union officials had actually sold their members out to Fiat Chrysler, as the No. 3 U.S. automaker was then known. (After a subsequent corporate merger, it is now called Stellantis.) It was cheap enough: The company spread $3.5 million around to get the UAW leadership to betray the membership from 2009 through 2016.

Fiat Chrysler “conspired to make improper labor payments to high-ranking UAW officials, which were used for personal mortgage expenses, lavish parties, and entertainment expenses,” said Irene Lindow, a special agent with the Department of Labor Office of Inspector General, in March 2021, when the company was hit with a $30 million fine. “Instead of negotiating in good faith, [the company] corrupted the collective bargaining process and the UAW members’ rights to fair representation.”

Thanks to a court-appointed special master and a referendum, all of the UAW’s active and retired workers got to vote for a new president. Shawn Fain, an electrician who formerly worked at the Chrysler transmission plant in Kokomo, Indiana, won in a runoff election, beating incumbent Ray Curry by less than 500 votes out of almost 140,000 cast.

In an online candidates’ forum, Fain blasted the UAW’s incumbent leaders. “I am running because I am sick of the complacency of our top leaders,” who he claimed had viewed the auto companies “as our partners rather than our adversaries” and had feathered their own nests with “wage increases, early retirement bonuses and pensions,” even as rank-and-file members were never made whole after making major concessions during the Great Recession of the late 2000s.

Fain has described the current labor action against the big three as much larger than one union and the auto industry. “If they’ve got money for Wall Street, they sure as hell have money for the workers making the product,” he said. “We fight for the good of the entire working class and the poor.”