The warning came over the radio just as tanks rumbled into Prijedor in northwestern Bosnia on a gray April morning in 1992. All Muslim men and boys aged 12 and older were ordered to leave their homes and line up in the street. Enesa Krupić’s mother, calling from another city, told her Serbian soldiers, following orders from then-president Slobodan Milošević, were moving block by block — tanks in front, troops behind and empty buses in between. The buses weren’t just for show.

One by one, men and boys were being loaded into the buses and taken away from the town in northwestern Bosnia and Herzegovnia to concentration camps.

Krupić was four months pregnant. Her husband Nijaz had just been fired, along with every other Muslim man at his workplace. Her father-in-law’s pension had stopped arriving. Food was running low. And now, the soldiers were at her door.

“My husband turned around and said, ‘Be safe,’” Krupić, now 55, said. “My brother-in-law — he knew. He told me, ‘If my wife calls, don’t tell her we are gone.’”

The soldiers entered, checked the men’s IDs and searched their rooms for weapons. Despite finding nothing, the army took her husband and his four brothers. The five men were loaded onto a waiting bus.

Three decades have passed since that morning in Prijedor. But for survivors like Krupić, the memory remains sharp, intimate and unresolved.

Three decades have passed since that morning in Prijedor. But for survivors like Krupić, the memory remains sharp, intimate and unresolved. That was the last time she ever saw her brother-in-law Fehim. He was later killed in a camp. She would see Nijaz again — but months later, after risking everything to try to bring him home.

July 11 marked the 30th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre and, more broadly, the Bosnian genocide, one of Europe’s most brutal — and often overlooked — atrocities of the 20th century. The massacre was one of the most horrific chapters in a war that began after Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia.

The former Yugoslavia had been a fragile, polyglot federation cobbled together after World War I and reconstituted under communist rule following World War II. For decades, it maintained a delicate balance among its six republics — Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Macedonia — and its patchwork of ethnic and religious groups. That balance began to unravel in the late 1980s, as nationalist tensions surged across Eastern Europe.

In Serbia, Slobodan Milošević rose to power by exploiting ethnic grievances and consolidating control over key institutions. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia began to splinter. Slovenia and Croatia broke away in 1991; Bosnia followed in 1992. Milošević decided to carve out a “Greater Serbia” — a campaign to unify all Serb-inhabited territories, even those outside Serbia’s official borders — and backed Serbian forces in Croatia and Bosnia in a campaign of ethnic cleansing that culminated in the 1995 genocide at Srebrenica.

According to the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the war, which lasted from April 1992 to November 1995, displaced more than 2 million people — accounting for half of Bosnia’s population — and resulted in at least 100,000 deaths. Driven by ethnic nationalism and the vision of a “Greater Serbia,” Bosnian Serb forces launched a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing, targeting Bosniak Muslims and Croats. In Prijedor alone, an estimated 30,000 people were detained, and more than 3,000 were killed, most of them Bosniak civilians, as documented by the U.N. Refugee Agency.

Tens of thousands of others were displaced, seeking asylum in countries throughout the European Union, such as Sweden and Austria, and in the United States. In 1991, before the conflict, there were about 15,000 Bosniaks living in the U.S. Today, according to the Congress of North American Bosniaks, an estimated 350,000 people of Bosnian descent live in North America. Of those, the vast majority are either genocide survivors or the descendants of those who fled because of it. While not all arrived as refugees themselves, most came to live in the U.S. as a direct consequence of the war.

“The damage was lasting”

After soldiers arrested Krupić’s husband and brother-in-law, she had no idea where the men were taken. It wasn’t until whispers began circulating that Muslim men were being held in a ceramics factory on the edge of town that she got on a bicycle and rode across Prijedor.

“Whoever went there didn’t come back,” Krupić said.

The factory was called Keraterm, an abandoned ceramics plant surrounded by barbed wire, cement walls and guard patrols. Staffed not only by soldiers but, in some cases, even by armed children, it had been converted into one of three major concentration camps established by Bosnian Serb forces in the Prijedor region in the spring of 1992. Along with Omarska and Trnopolje, the camps formed part of a coordinated system of ethnic cleansing by Milošević’s regime.

While the brothers were imprisoned in Keraterm, prisoners were not only starved and beaten, they were also systematically humiliated for their faith. “They would force-feed them pork and make them curse Allah,” said Krupić’s daughter, Amila Tutundžić. “They made them sing nationalist songs — songs about Greater Serbia and against Muslims. It was all about breaking them down.”

Some of the most disturbing acts were designed to psychologically destroy prisoners. Guards would identify fathers and sons held together, hand them metal rods and force them to fight to the death while soldiers watched and laughed. In other horrific instances, Krupić said, detainees, including family members, were coerced into sexually violating each other under threat of execution.

“My dad doesn’t like to talk about it much,” Tutundžić said. (In a later text message, she clarified that he had experienced “too much PTSD and trauma.”) “But I remember one thing he mentioned — that they would sexually assault men with bottles. What he went through was even more traumatic than what my mom experienced.”

Nijaz was eventually transferred to Trnopolje, a different type of detention center three to four miles southeast of Prijedor. Trnopolje functioned less as a killing camp and more as a transit site, used to detain civilians before expelling them or redistributing their homes.

Fehim was left behind at Keraterm and forced to help bury corpses. When he was no longer needed, Krupić learned, he was buried alive with the other victims.

Tutundžić said that, unlike her mother, who often spoke about the war, her father rarely shared his memories. The trauma, however, was impossible to hide.

“Even after he came home he wasn’t the same,” she said, “You could see it in his eyes. Something inside him never came back.”

The damage was lasting.

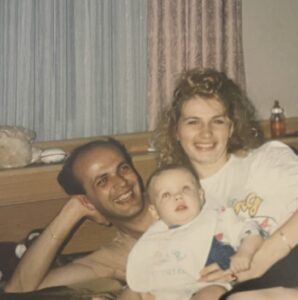

(Courtesy of Amila Tutundžić) Krupić with her husband, Nijaz, and daughter, Amila, in Germany after fleeing Bosnia.

“I remember vividly my dad waking up in the middle of the night for years, screaming in terror because he was having nightmares,” she said. “That part was hard to navigate, because nobody really understood it.”

Krupić believed she and her husband would be safe after she was forced to sign over all their family property to Serb authorities to secure his release — an act so common across Prijedor that, by war’s end, an estimated 50,000 Bosniak homes had been seized, with many still occupied by Serbs decades later.

The couple’s reunion was short-lived.

Deceived by promises of safe passage by authorities, they were instead taken together to Trnopolje — the second time for Nijaz — at some point in the late summer or autumn of 1992. Like many survivors of trauma, their memories of exact dates are hazy. There, in a detention center, they slept on a school stairwell and survived on sporadic deliveries of powdered milk.

A staged photograph of Krupić, nine months pregnant with Amila, was later published by Serb media as propaganda, meant to suggest that prisoners were safe and cared for. “They came in with cameras,” she said. “Told me to smile.” In her time during the detention center, she did not receive any medical care.

After about a month, she and Nijaz were finally released from the detention camp in December 1992. The very next day, she went into labor and gave birth to their daughter. Less than a month later, the family fled Bosnia by illegally crossing into Slovenia — Krupić with newborn Amila and her elderly parents, while Nijaz went alone through forests and rivers — and little more than hope. From there, they went to Germany, where they were granted asylum alongside an estimated 320,000 other Bosniaks. After several years there, they boarded a plane to St. Louis, Missouri, and never looked back.

But the past always had a way of resurfacing.

Years later, as a teenager in the United States and a curious daughter of survivors, Tutundžić began searching for answers about Fahim, the uncle she had never met. That quest led her to a war crimes tribunal transcript. In it, she found his name listed among the detainees of Room Two in the notorious Keraterm camp — where men were forced to bury the dead before being executed themselves.

“Even decades later,” she said, “We live with the echoes.”

A war correspondent reflects

(Courtesy of Carol J. Williams) Carol J. Williams, a war journalist, documented stories like Enesa’s for her entire career.

Horrors like those experienced by Nijaz and Enisa Krupić, along with their families, were the very ones Carol J. Williams spent years as a foreign correspondent covering the Balkans and other war zones for the Los Angeles Times and the Associated Press.

Now 69, Williams was stationed in the region throughout the 1990s, bearing witness to what she now calls some of the darkest scenes of her career.

In all her years reporting from war zones, she said she will never forget a little boy in one of Sarajevo’s overrun hospitals.

“His face was missing because part of the shrapnel from the bombing at the school had taken out an eye, about half of his face, his nasal passages,” Williams said. “Part of the kid was just laying there shaking. He just kept asking for his parents.”

The boy had survived a Serb artillery strike on his school — part of a broader campaign of terror during the nearly four-year siege of Sarajevo. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), more than 50% of the city’s 240 schools were damaged or destroyed during the war. Schools, hospitals and marketplaces were frequently targeted, despite international prohibitions against attacking civilian infrastructure.

Williams had brought a couple of chocolate bars with her to the hospital, rare luxuries in a city surviving on flour, water and rationed aid. She gave one to the boy. “To him,” she said, “it was like giving a million dollars to an adult.”

Later, with temperatures plummeting to six degrees below zero in the cruel Bosnian winter, she climbed nine flights of stairs to find the boy’s family. The father bore the same injuries as his son — his eye and face were shattered by shrapnel. The family had been displaced from their home and were squatting in an abandoned apartment, its former Serbian residents having long since fled. The only heat came from blankets and shared body warmth. Williams gave the second chocolate bar to the family’s three-year-old daughter, Edina. Malnourished, with bulging eyes and a skeletal frame, she unwrapped the foil slowly, took a few small bites and then paused.

“I have to save the other half for my brother, because he’s sick,” she said through a translator.

To Williams, the little girl’s humanity was overwhelming.

In Bosnia, even journalists weren’t spared the cold and danger. Williams and other foreign correspondents were based at the Sarajevo Holiday Inn, a once-glamorous hotel built for the 1984 Winter Olympics, which had since been turned into a shell-scarred outpost that was routinely targeted by Serb artillery. Not a single room had intact windows.

“Bosnian winters are brutal — minus 20,” Williams said. “You’re in a hotel room with no electricity, no water and a sheet of plastic flapping where your window used to be.”

The U.N. eventually sent rolls of thick plastic to replace the shattered glass, but it offered little insulation against the bitter cold and relentless shelling.

Night after night, reporters calculated the odds of mortar fire hitting their room.

The U.N. eventually sent rolls of thick plastic to replace the shattered glass, but it offered little insulation against the bitter cold and relentless shelling. Night after night, reporters calculated the odds of mortar fire hitting their room.

At least 21 journalists were killed covering the Bosnian War, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Many more were injured or psychologically scarred by what they saw.

“I can’t tell these stories without breaking down,” Williams said.“[Bosnians] were the wronged party — driven out of their homes simply because another ethnic group wanted that territory.”

As the violence escalated, the U.N. declared six “safe zones” in Bosnia — including Sarajevo, Srebrenica and Žepa — but those enclaves were repeatedly violated by Serb forces. The most notorious failure came in July 1995, when thousands of Bosniak males were massacred in the Srebrenica safe zone, despite the presence of U.N. peacekeepers. Bosniak men and boys — some barefoot, others gripping ID papers — were separated from their families. Blindfolded and bound, they were herded into gyms, warehouses and fields, and then executed en masse. While some were killed with single shots, others were gunned down in groups. Those who fled were hunted through the woods by dogs and soldiers with night-vision scopes.

Such terror tactics and violence were routine for Bosnian Serb forces under Milošević’s leadership, reflecting a broader campaign of ethnic cleansing that would later extend beyond Bosnia. In the late 1990s, his forces carried out a brutal crackdown in Kosovo against ethnic Albanians, drawing international condemnation and eventually leading to NATO intervention.

Milošević, the first European head of state to be prosecuted for genocide and crimes against humanity, died of a heart attack in 2006 before his trial at The Hague could conclude — but he is still widely held responsible for orchestrating the ethnic violence against Bosnians.

“It wasn’t a civil war”

(Pool Photo/Getty Images) Former President Slobodan Milosevic is surrounded by guards as he sits before the U.N.’s International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague on February 13, 2002.

In 1992, after the fall of the Soviet Union the previous year, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence from Yugoslavia and established a multi-ethnic government led by its first president, Alija Izetbegović, a Muslim intellectual and longtime advocate for a sovereign Bosnia. But the move was violently opposed by Bosnian Serb leaders.

David L. Phillips, who served as an adviser to Izetbegović during the war — and as a senior adviser to the State Department Bureau for European Affairs from 1999 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton — has spent decades studying and writing about genocide prevention. For him, the failure to stop the mass killing remains one of the most damning indictments of international diplomacy since the Holocaust.

“There were 63 U.N. Security Council resolutions on Bosnia,” he said. “None of them were effective in stopping the bloodshed.”

This failure has a modern parallel: Since October 7, 2023, the U.N. has passed at least 14 resolutions related to the Gaza conflict. However, much like during the Bosnian war, these resolutions have largely failed to halt the violence or alleviate the humanitarian crisis on the ground in Gaza, where aid groups say the most vulnerable will soon be facing famine.

“What I remember most [about Bosnia] was the ineptitude of the international community to stop the genocide from happening,” Phillips said.

Among the most crippling procedural flaws, Phillips said, was the “dual key” policy; both the U.N. and NATO had to authorize any military action before it could be taken. This system made it nearly impossible to respond swiftly to atrocities on the ground. Even when genocide was unfolding in real time — through mass killings, systematic rape and forced deportations — international forces were hamstrung.

Meanwhile, Bosnia’s government was not allowed to adequately defend itself, he said. A U.N.-imposed arms embargo, which was initially intended to prevent escalation, instead ultimately disarmed the victims while their aggressors remained heavily equipped.

In Washington, the Clinton administration, wary of committing American troops to another Somalia-like fiasco, resisted direct military involvement until after the 1995 Srebrenica massacre. Only then did the U.S. lead a decisive NATO air campaign that finally forced Bosnian-Serb leaders to the negotiating table, setting the stage for the Dayton Peace Accords in 1995 that ultimately ended the conflict.

“It wasn’t a civil war,” Phillips said. “It was an act of Serbian aggression, and the Bosnians were defending themselves — without adequate arms, under an embargo, abandoned by the world.”

While there is broad scholarly consensus that the Bosnian genocide occurred, only the massacre in Srebrenica — a town in eastern Bosnia — has been legally recognized as genocide by the ICTY in 2004, a designation later affirmed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2007.

Despite clear evidence of ethnic cleansing as early as 1992, including detention camps, mass graves and widespread sexual violence, decisive action by the international community was delayed. It wasn’t until NATO launched airstrikes in 1995, after years of stalling, that the conflict began to shift. By then, most of the damage had already been done.

In July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces overran Srebrenica and executed over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys, despite the presence of Dutch U.N. peacekeepers, who failed to intervene. This was regarded as the final horrific act, adding to the over 100,000 people who had already died, according to widely cited research by the Research and Documentation Center (RDC) in Sarajevo, published in “The Bosnian Book of the Dead“ in 2007.

Today, Phillips sees Bosnia, which he described as “preventable,” as a warning and symbol of what happens when the international community confuses neutrality with inaction and peacekeeping with passivity.

Today, Phillips sees Bosnia, which he described as “preventable,” as a warning and symbol of what happens when the international community confuses neutrality with inaction and peacekeeping with passivity.

“Genocide prevention is not about trials after the fact,” he said. “It’s about political leadership at the moment of crisis. And in Bosnia, the world failed that test.”

The pain — and power — of remembering

(Pierre Crom/Getty Images) The coffins of seven Srebrenica genocide victims recently identified are carried to the Potocari cemetery by relatives and friends on July 10, 2025 in Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

For survivors like Krupić and her daughter Amila, memory is not confined to the past. It is relived daily through stories passed down, names found in tribunal transcripts and artifacts pulled from mass graves. But individual remembrance is only part of the story. What lingers, even 30 years later, is a broader struggle over whose memory becomes history — and whose trauma is erased.

Douglas Becker, an expert on historical memory and political identity at the University of Southern California, argued that Bosnia remains a case study in the political power of remembering. “You can’t view any sectarian issue in Bosnia without thinking about the genocide,” he said. “It plays such a huge role.”

In Becker’s view, memory does not just reflect the past — it shapes the present. From regional politics to diasporic identity, how history is remembered determines how communities engage with one another.

“Families tell these stories all the time. What happens to those stories then, in context, is what’s really fascinating.” That context, whether defined by justice, denial or silence, can either foster peace or entrench division.

We need your help to stay independent

For many in Bosnia and abroad, forgetting is not an option. “The most powerful form of memory entrepreneurship is recovery of invisible communities,” Becker said.

Survivors become witnesses. Daughters become archivists. The personal, as in Krupić’s case, becomes political. And yet, memory is contested.

(Courtesy of Amila Tutundžić) Three generations of Kuprićs. Mother, daughter and granddaughter.

In Serbia, some political leaders have pushed to reframe the war, positioning Serbs as equal victims. This, Becker noted, is part of a larger pattern. “We want our narratives to have white hats and black hats. But the best you can hope for is a recognition that it’s all traumatic — let’s make sure we never go back to war.”

That reframing is playing out not only in cultural narratives, but also in courtrooms. Just this March, after convicting him of undermining the country’s constitutional order, Bosnia’s state court issued an international arrest warrant for Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik, who had defied international rulings by signing laws weakening the powers of Bosnia’s constitutional court. Since the Dayton Peace Accords brought an official end to the Bosnian war, Interpol declined Bosnia’s request for a red notice — an international alert used to locate and provisionally arrest individuals wanted for prosecution or to serve a sentence — citing concerns the warrant for Dodik’s arrest was politically motivated. The case has heightened regional tensions and underscored the fragility of post-war governance in the nation, where memory and legality remain deeply entangled.

Ultimately, though, memory work is not just about recounting what happened, Becker observed. It’s about building the world that comes after. “Understanding historical memory,” he said, “is about understanding empathy.”

This is why Krupić continues to share her story. She and her family still live in St. Louis. The city, which is home to the largest Bosnian population outside of Europe, estimated at 50,000 to 70,000 people, has come to be known as “Little Bosnia.”

On quiet days, she remembers those she lost. Her brother-in-law, who died in captivity in Keraterm. And then Fehim, whose remains were finally identified nearly 20 years after his death at Keraterm. Krupić pulls out a faded photograph of Fehim and shows it to her daughter, who was born into war and raised in its shadow. She remembers her other brother-in-law who also died in Keraterm. Now, Amila shows it to her own children — four and eight-years-old — who were born in America, thousands of miles from the camps and killing fields of Prijedor.

Through generations, the family keeps the memories close. “They took everything,” Krupić said. “But we kept the truth. You can rebuild homes, but some wounds stay open. That’s why we keep telling the story.”

Read more

about this topic