Sitting next to Bahrain Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, who stared ahead awkwardly, President Donald Trump carried on with one of his wandering soliloquies in front of reporters on July 16 in the Oval Office. With his typical bravado, Trump emphasized his suspiciously instant positive effect on the U.S. economy, telling the media, “Everyone would say we are the hottest country anywhere in the world. We were a dead country a year ago, and now we have the hottest country.”

Two weeks later, after the release of the latest gross domestic product readings, Trump continued his blitz messaging campaign on Truth Social: “2Q GDP JUST OUT: 3%, WAY BETTER THAN EXPECTED!” Yet despite his unrivaled self-promotional marketing skills, the president has left many wondering whether we really are better off than a year ago.

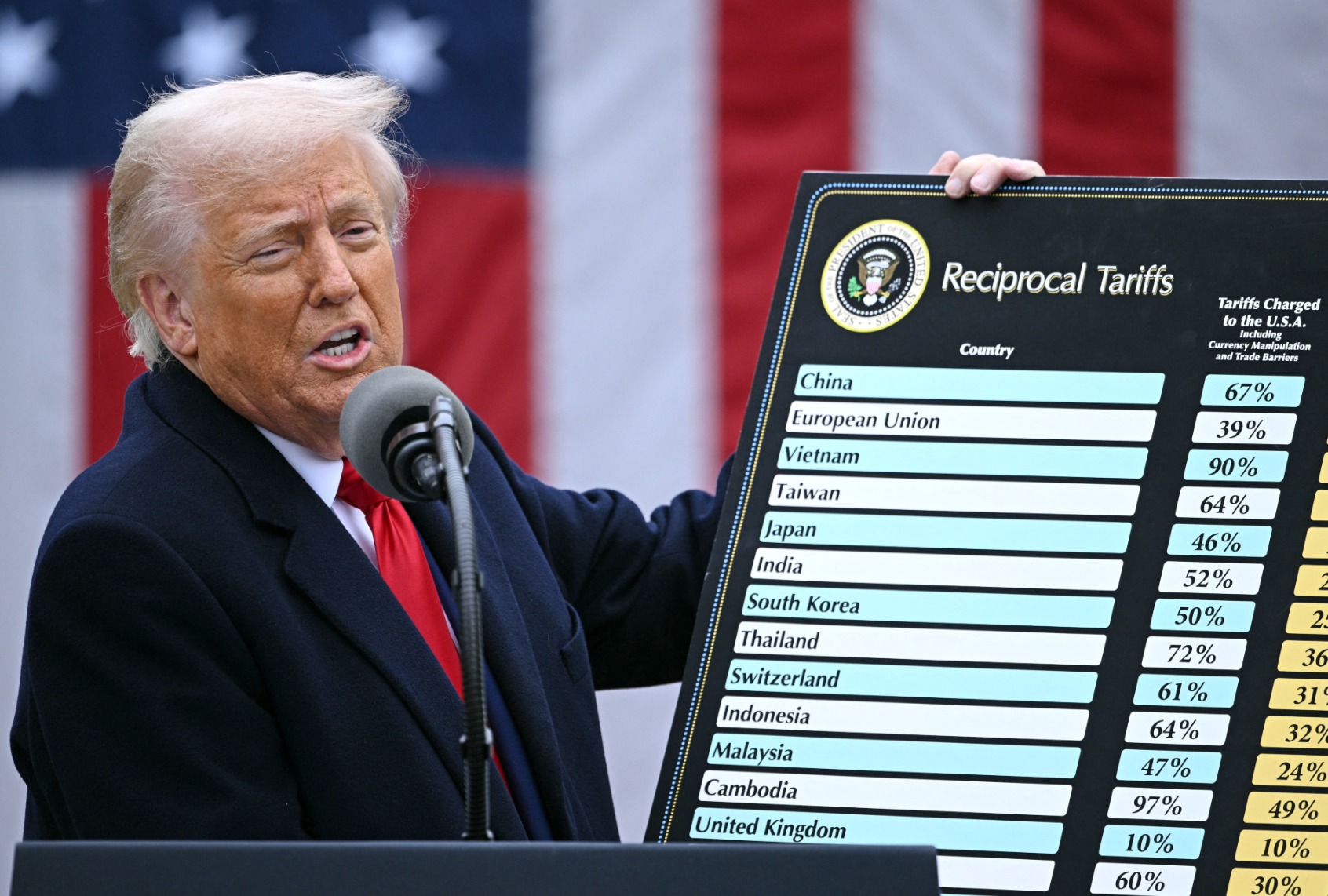

Since Trump’s so-called Liberation Day on April 2, many economists have revised their GDP growth estimates downward for the years ahead and kept them well below the U.S. historical average, even after the president’s much-ballyhooed trade deals have been announced.

GDP growth came in strong for the quarter, but only after contracting by one-half of a percentage point in the prior three-month period, leading to an economy that grew by a meager 1.2% on an annualized basis.

Trump’s sporadic tariff policies are to blame for the volatile first half of the year, and his erratic announcements have earned him the sobriquet “TACO Trump” — as in Trump Always Chickens Out. He continued this practice on Thursday, when he announced he was postponing raising tariffs on Mexico for 90 days. (He also raised tariffs on Canada ahead of an arbitrary midnight deadline.)

In the longer term, the tariffs leave projections looking weaker all around. Growth estimates for 2025 are coming in at 1.4%, compared to 2.8% in 2024. Since Trump’s so-called Liberation Day on April 2, many economists have revised their GDP growth estimates downward for the years ahead and kept them well below the U.S. historical average, even after the president’s much-ballyhooed trade deals have been announced.

Some argue that a little economic pain is necessary as Trump cleans up “the mess” left by former President Joe Biden, pointing to large budget deficits, regulatory overreach and industrial policy interference. Unfortunately, the projected budget deficit is expected to be even worse than it was a year ago, and the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” has only made the 10-year debt outlook more ominous. While the previous regulatory regime froze nearly all mergers and acquisitions deal flow, championed pro-union labor laws and increased environmental protections, the new one requires veiled monetary and non-monetary contributions, mandates ideological concessions and directs predatory harassment towards disfavored parties. If the Biden administration can be blamed for picking favorite industries, what about the Trump administration’s sectoral tariffs and generous posture toward cryptocurrencies and fossil fuels?

Admittedly, Trump’s bullying tactics may provide some temporary cosmetic benefits to the U.S., as he threatened far worse than he executed. Still, the harm to America’s credibility and its relations with international partners is far more costly over the long run. The use of tariffs against countries, such as Brazil and Canada, to advance personal political agendas certainly looks like an abuse of power. Such actions might be acceptable in authoritarian regimes, but not in democratic countries. These moves are just another example of the president crossing lines previously never considered. His invocation of wartime powers through the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 to employ many of his tariffs has rightly been called into question by federal courts.

However, damage from the Trump tariffs extends beyond international relations and basic concerns about the federal government subtly interfering in the free market. Tariffs have fundamentally disrupted markets, leaving businesses vulnerable to the double threat of uncertainty and cost inflation.

Certainty does not appear to be coming anytime soon for business leaders. Of the more than 180 countries affected by the tariffs, only nine deals have been announced. And any possibility of a long-term deal with China, Mexico and Canada — the U.S.’s largest trade partners — continues to evade the administration. Despite financial markets oddly rallying to all-time highs on the news of trade deals that increase effective tariff rates by more than fivefold, it is worth noting that the announcements are only “frameworks” of a deal.

Many of the critical details remain to be agreed upon. For instance, the proposed pact with the European Union still requires both sides to draft a legally binding document. In addition, members of the bloc must reach consensus to approve the legal text, a process that often takes years. Notably absent from the framework was the future of the contested digital services tax on U.S. tech companies.

Other aspects of the trade deals are also less firm than markets may like to believe. The $600 billion investment by the European Union is simply a collection of soft pledges — or vague “frameworks” by European companies. The $550 billion investment commitment from Japan was quickly touted by the administration but soon became a source of concern among many after each side offered different accounts of the commitment.

Direct tariffs on steel, aluminum, automobiles, automobile parts and copper, with more expected on pharmaceuticals, timber, lumber and semiconductors, disincentivize growth and investment in the very industries that Trump is attempting to attract. Many have significantly reduced their expected growth in fixed capital investment. Moreover, they put U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage against their international rivals.

The most glaring example is the disparity in tariff rates between foreign and domestic auto manufacturers. Trade deals with Germany, Japan and South Korea now place their automakers at an advantage for all cars imported into the U.S. Even though a greater share of their cars are made in America, Ford, General Motors and Stellantis are paying a full 10 percentage points more than the likes of Mercedes-Benz, Toyota and Kia. The Big Three U.S. automakers expect to pay almost $10 billion collectively in additional costs due to tariffs.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only, written by Amanda Marcotte, now also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

This punishment of American automakers is hardly making our trading partners pay to the advantage of U.S. consumers and workers. Other industries with iconic American brands, like Dow, American Airlines, Nike, Gap and Procter & Gamble, have also reported the steep prices paid as a result of the Trump tariffs. Many of those companies are now being penalized by the same president who pushed them during his first term to diversify their supply chains away from China and into other countries. Most have not yet passed on the costs to consumers, but tight margins will ultimately require them to do so once they have a better understanding of the tariff costs and drawdown on inventories. Economists from J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs expect that move to occur in the second half of the year.

Some industries, however, do not have time to wait to adjust prices. As Trump continues to chide Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on rate cuts and their impact on home prices, the president forgets to mention that he needs Powell to help him offset the costs of building a home because of his tariffs. According to the April NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index, suppliers immediately increased prices by more than 6% in response to Trump’s tariffs. The average cost increase per home was expected to be $10,900.

Ultimately, most companies substantially impacted by the tariffs will need to share the cost burden with consumers. The average direct cost to consumer households is approximately $2,400, according to estimates. Other costs are more indirect, such as a slowdown in hiring plans, particularly among small businesses. The actual effects of Trump’s economic agenda are becoming more evident in the latest economic reading. A marked slowdown in private business investment and consumer spending occurred, with growth dropping to 1.2% from 1.9% last quarter. But both figures are still lower than the 2.9% seen under Biden’s final quarter in office.

We need your help to stay independent

As with any news story, artificial intelligence has and will continue to be an essential factor in the economic trajectory. For Trump, this technology has been his saving grace. The economy has been buoyed by the trillions of dollars invested in the AI arms race, along with early productivity gains from its applications. While Trump may consider himself lucky, American exuberance can only look past so much. Over time, more businesses and consumers will start to realize how much better off they would be without the tariffs.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and Special Trade Representative Jamieson Greer are sophisticated professionals with no bravado or threats. When they have stepped in after initial assaults, they have shown keen recognition of the economic sensitivities and have played a moderating role in the Trump administration. But the unconventional Trump negotiating style is not anchored in building long-term trust. Rather, it relies on beginning with a punch in the nose so that an outstretched hand, offering little but not a slap, is received with relief. As skilled professionals like Bessent and Greer step in, they mop up the blood rather than adding a “one-two punch” follow-up like Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick.

But their efforts to clean up in Trump’s wake are often too little, too late for our allies, who are tired of being abused. While America’s relationships with them remain strained, our adversaries are making consequential inroads.

Read more

about this topic