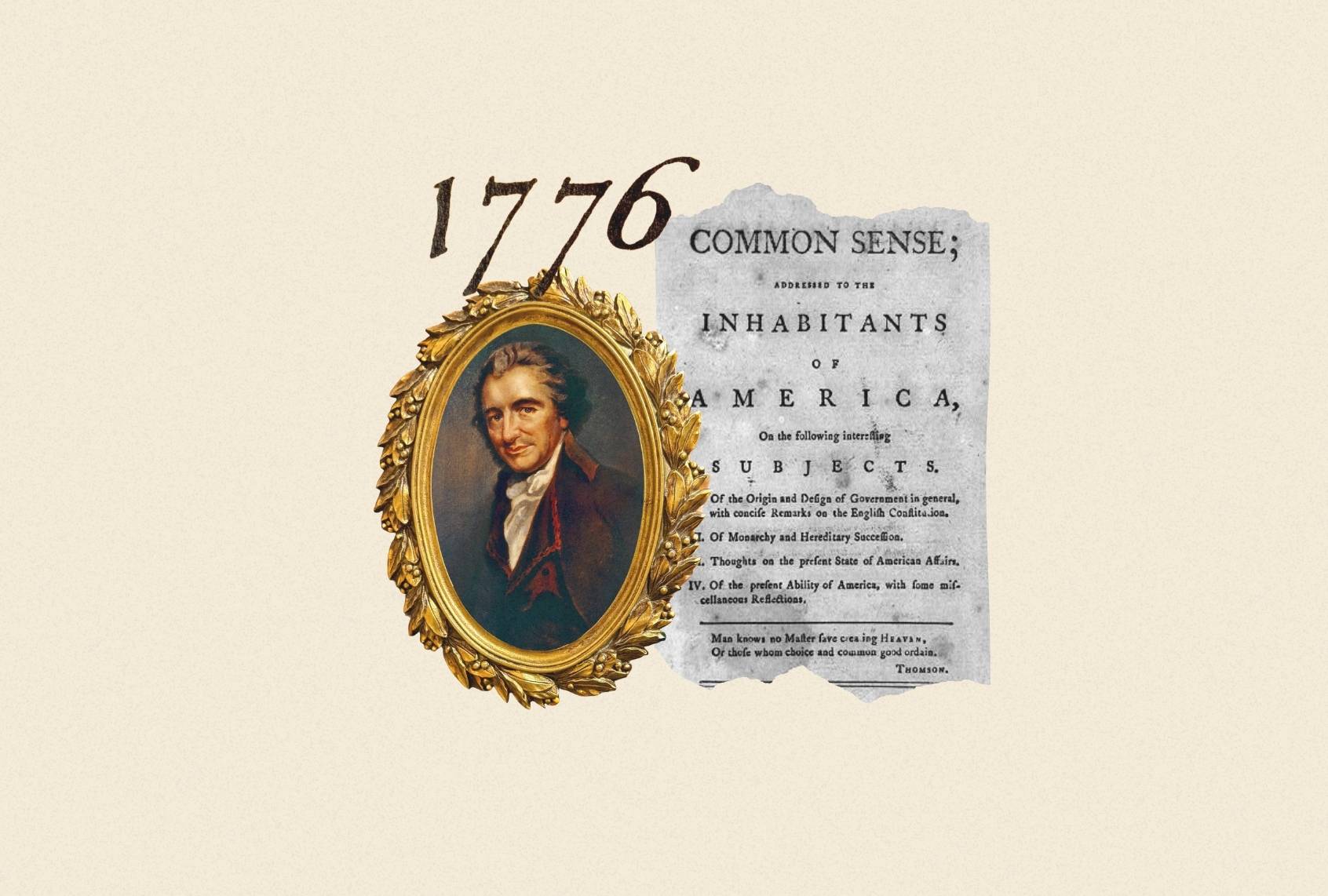

Two hundred-and-fifty years ago, on Jan. 10, 1776, Thomas Paine published words that changed the course of history: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” Characterized by Paine as “nothing more than simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense,” his words transformed a colonial fight for rights under royal rule into a globally significant revolution for liberty under representative government.

Paine’s timing for “Common Sense,” the first widely-read pamphlet proposing independence rather than pleading for rights and reconciliation, was perfect. Only a year earlier, his words would have not been taken seriously. Patriots had been fighting for their rights as British subjects since the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765, the result of Parliament imposing taxes on colonists who were not represented in that body, but they had always looked to the king for relief.

Even after adopting the militia forces besieging British troops in Boston following the Battles of Lexington and Concord as a Continental Army in 1775, Congress declared, “We have not raised Armies with the ambitious Designs of separating from Great-Britain” but “in defense of the Freedom that is our Birth-right” as subjects of the king. Reinforcing this point, Congress then sent its Olive Branch Petition to George III declaring the fidelity of colonists “to your Majesty’s person, family, and government” and asking him to rein in Parliament.

The king refused to receive the petition and instead proclaimed “the colonies in open and avowed rebellion,” and he vowed to crush with the largest army and navy Britain had ever dispatched overseas, which included legions of paid German mercenaries. George’s response reached most colonists in early January, along with news that to start the new year, a royal navy squadron had bombarded Norfolk, then Virginia’s principal port, followed by fires that destroyed the city.

Urged on by patriot leader Benjamin Rush and advised by Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Adams, Paine had been working on “Common Sense” for months. The pamphlet changed the way Americans viewed government. Beginning with an origin story that echoed John Locke’s “Second Treatise of Government,” Paine depicted people originally created free and equal in nature and subsequently forming representative governments to better secure their liberty and happiness.

Monarchy, he argued, had upended this natural order. Taxation without representation was but a predictable consequence of placing power in any person or institution other than the people or their freely and fairly elected representatives. “The palaces of Kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of Paradise,” Paine wrote. Through graft, grift and self-serving decrees, authoritarian leaders inevitably serve their own interests rather than the people’s.

Want more sharp takes on politics? Sign up for our free newsletter, Standing Room Only, written by Amanda Marcotte, now also a weekly show on YouTube or wherever you get your podcasts.

At a time when absolutist regimes ruled most of the globe and threatened to engulf the rest, “Common Sense” called for popular governments with frequent elections to assure “their fidelity to the Public will.” Asserting that “monarchy and succession have laid (not this or that kingdom only) but the world in blood and ashes,” Paine wrote that “Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.”

Almost overnight, the king replaced Parliament as the symbol and target of colonial grievance, and gaining independence under popular rule became the patriot aim. Within weeks of its publication, “Common Sense” became the bestselling pamphlet of its era. At a time when even the largest American newspapers rarely had circulations exceeding 2,000, over 100,000 copies of “Common Sense” flew from patriot presses by mid-April and reached some 500,000 by 1778. “It was read by public men, repeated in clubs, spouted in schools and in one instance delivered from the pulpit instead of a sermon,” Rush observed, with other patriot leaders from New England to the Carolinas attesting to its impact. Noting that the pamphlet “is working a powerful change in the minds of many men,” George Washington had it read aloud to the troops besieging Boston.

Paine’s soaring words gave voice to an emerging spirit that lifted colonial resistance to imperial tax policy into a global revolution for liberty under law. “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind,” he proclaimed at the outset. In the 80-odd pages that follow, “Common Sense” eloquently depicted “liberty and security” as the proper “end of government,” lucidly outlining a democratic one calculated to advance “the greatest sum of individual happiness with the least national expense” and glibly assuring readers that, for such a cause, Americans could prevail against all the force that Britain could project against them.

We need your help to stay independent

Life, liberty and happiness stand as founding ideals in “Common Sense,” much as they would in the Declaration of Independence six months later. “The will of the king (or a man) is as much the law of the land in Britain as in France,” Paine stated. Then he turned for emphasis to the fonts available on the printing press of his day. “In America the law is king,” he wrote in all capital letters. “For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King.”

Popular rule became the animating spirit of 1776, and it remains the reason why “Common Sense” still matters. A quintessentially American document that became foundational for the ideals of the emerging republic, it denounced authoritarianism in all its forms, called for radically representative government, embraced an almost libertarian sense of individual liberty and pointed toward political equality for all.

Although rooted in writings of the 18th-century European enlightenment, these ideas sprouted in the American soil of an expanding frontier where economic opportunities fed and were fed by political independence, legal liberties and social equality. To my mind, there is no better way to celebrate the nation’s 250th anniversary than rereading “Common Sense.”

Read more

about this topic