By the time August rolls around, we’ve already sated ourselves on the junk reading of summer, while book publishers are saving their best stuff for the fall. No wonder they call these the dog days. Nevertheless, Salon’s fiction scouts roused ourselves from our torpor and set out in quest of that most elusive of trophies: the good August novel. Much to our delight, we managed to rustle up a handful of real gems. What’s notable about many of this month’s selections is that some of us began to read our books with low expectations — another thriller, another family drama, another AIDS novel and, oh no, could this be an Oprah book? — only to find our flip-flops knocked off. So lament not, summer readers: There’s just enough here to stock your bedside table before the September rush, from a humid Southern drama of race and destiny to the story of a woman grappling with “a true maternal monster.” Dig in.

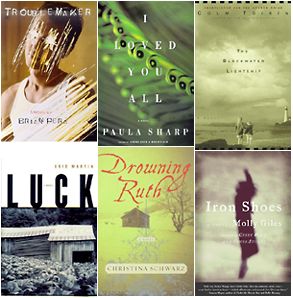

Drowning Ruth

By Christina Schwarz

Doubleday, 400 pages

Like a master chef who can transform a few simple ingredients into a delectable meal, first-time novelist Christina Schwarz starts with some basic, not to say old-fashioned, fictional elements. She begins with two sisters, one vivacious, pretty and married, and the other overshadowed and single; an isolated lakefront community in rural Wisconsin during the early 20th century; a mysterious baby; a bitter winter night that ends with one sister drowned. Then she follows the family until, years later, the love, renunciation and envy that shape this story rumble to their final resolution.

The result is an absorbing tale in which, remarkably, the suspense comes from the unfolding of its characters — people as complex and surprising as anyone you might actually know. Schwarz keeps her reader guessing without resorting to cheap tricks. Mattie Starkey is captivating and bold as she wins the heart of Carl — a meatpacker who doesn’t take easily to working Mattie’s father’s farm and so enlists to fight in World War I, leaving his wife behind with a small child, Ruth. But in her recklessness and insensitivity to her hardworking sister, Amanda, Mattie also shows the blithe narcissism of the innately charming. Amanda — possessive, tart, diligent — fumes inwardly to see her beloved sister taken away by a man she dismisses as “nothing special.” With her crabbed spirit and her occasional bouts of mental illness, is she capable of serious wrong? If not, then how did she acquire the bite-shaped scar on her hand the night Mattie died?

Amanda shoulders the task of raising Ruth and, eventually, the care of her war-wounded brother-in-law, but their peaceful household suffers some fissures when an old flame of Amanda’s moves to the town and the teenage Ruth befriends a glamorous classmate. All this is set amid a palpable Great Lakes landscape of sheep meadows, country stores, potato fields, 1920s boating parties and treacherous winter ice. When the cracks in Amanda’s fiercely protected life begin to widen, the secrets that seep through defy expectations, and most readers will be entirely under Schwarz’s spell.

— Laura Miller

Luck

By Eric Martin

W.W. Norton, 288 pages

As to the plot of this humid and turbulent first novel, I’ll leave the summary to Mike Olive, the protagonist, who tells himself the story in an effort to make sense of his life’s recently skewed arc: “A boy returns home, cranes his head around, and with his new inside-out eyes says, Something is wrong here. Some believe him. Some suspect him. He ignores everyone and everything he knows. He turns on his friends, his family, his enemies. He falls in love despite them all.”

Mike, of course, is the boy, a collegiate do-gooder home for the summer from Duke University. Home is Cottesville, N.C., a fictionalized little town with not much more to its shabby domain than a barbecue joint, a Stop ‘N’ Go and a thick wreath of tobacco fields. The “something wrong” is the ugly exploitation of Mexican migrant workers in those fields. And, finally, the despite-them-all love interest is an impudent teenage girl named Hermelinda, the daughter of a migrant worker newly arrived in Cottesville.

Mike hasn’t come home to bask between semesters: Armed with tape recorders, cameras and a tiny team of fellow Duke students, he sets out to document the ills being visited upon the Mexican workers, and hopefully, with a glint of youthful idealism in his eye, to fix those ills. But as so often happens in the South, applied idealism leads to violence, and as Mike burrows further into his cause (discovering in the meantime the “amazing difference between theory and practice”) Cottesville begins a violent unraveling.

There’s evidence aplenty of a Faulknerian curse-destiny here (“the violence of this land that roams unchecked in the August darkness”). The white tobacco farmers are entangled in a racial vortex not so different from that which ensnared their grandfathers, the distinction being as slender as the workers’ lighter-hued skin and their silkier-voweled language. But Martin’s purview, as suggested by his title, seems more existentialist, less aligned with Faulkner than with, say, Robert Penn Warren. As Hermelinda’s father tells her: “I think there isn’t any why, there’s only luck.” The South’s old and new troubles, Martin’s affecting debut seems to say, were built upon accidents of circumstance, of bad luck meeting bad luck on darkened dirt roads.

— Jonathan Miles

Iron Shoes

By Molly Giles

Simon & Schuster, 208 pages

Honestly, I was prepared to be bored and exasperated by this novel about a 40-year-old woman who is an emotional wreck and still at the mercy of her tyrannical, narcissistic parents. The book’s protagonist, Kay Sorenson, is a classic doormat, a klutzy, rumpled Northern California librarian and frustrated musician who is unhappily married to Neal, the vague, gray-ponytailed owner of a frame shop. Ida, Kay’s imperious, dying but still glamorous mother, pushes her daughter around, while Kay angles pathetically for scraps of attention from Francis, her distracted, equally hard-to-please father. Did I really want to spend a couple of evenings with this crowd?

As it turns out, I definitely did. “Iron Shoes,” Molly Giles’ first novel after two well-received story collections, is funny and intelligent, and when I finished it I was sad to see its characters go. Well, most of them, anyway: In Ida, Giles has created a true maternal monster, the kind of mother who brazenly steals the spotlight from her daughter by arriving late to her concert and coughing loudly throughout. Yet somehow Ida is a believable monster: a witty, beautiful, thoughtless force field of a woman so unprepared to surrender the advantages of youth that she seems to destroy her own body, as if to spite it. Drinking and smoking furiously, tossing off casual insults between lipstick applications, she bangs herself around and then refuses medical treatment until she has lost both her legs to gangrene.

While she’s still alive, Ida sucks up a lot of the novel’s oxygen, but she’s outrageously entertaining. After her mother’s demise, Kay has to figure out how to occupy the center of her own life without becoming as self-obsessed as Ida was. Even when the supposed problem is eliminated, Giles never pretends that such a thing is straightforward. “Iron Shoes” may be the story of Kay’s lurching steps toward a belated independence, but as a novel it’s always light on its feet — smoothly and gracefully written, and full of sly humor and wickedly good dialogue.

— Maria Russo

The Blackwater Lightship

By Colm Toibin

Scribner, 273 pages

A good novelist takes you to places in the imagination that are surprising and new. A very good one can lead you down roads you think you already know, and show you the power and poignancy of the familiar. In his fourth novel, Colm Toibin blends two of modern fiction’s most repeated motifs — the dysfunctional family brought together by AIDS and the wild, changeable landscape of Ireland as a metaphor for its people. But the commonness of the setup isn’t a sign of complacency on the part of the author: It’s an indication of someone so at ease with the everyday he has no need of theatrics.

At the heart of the novel is Helen, a loving wife and mother but an indifferent daughter and sister, who’s jolted out of her selective altruism by the specter of mortality. Her semiestranged brother, Declan, drops the bombshell that he’s dying of AIDS, setting in motion a series of events that gather an unlikely set of caretakers under the same roof. As they tend to the feverish, vomiting husk of the man Declan used to be, Helen, her mother, Lily, her grandmother and Declan’s gay best friends swap stories of growing up and coming out. They bicker among themselves, and they alternate between insight and misunderstanding. Declan is falling apart: Can the rest of them figure out how to come together?

Toibin captures his characters in the flickering moments that make up a day or a life: brushing hair or pouring tea. A life-and-death drama may be unfolding, but it’s in the quiet details that he reveals what’s starkly individual about the characters and reassuringly universal about the human condition.This is how we are, he says, gay or straight, sick or well, as we make sense of our families or just make breakfast.

Unlike any number of recent tear-jerkers, too eager to sanctify the sick and their loved ones, “The Blackwater Lightship” allows its characters to be flawed: frequently petty, controlling, fretful and resentful. Yet the story never strays too far in the opposite direction either: This is not yet another literary gathering of multigenerational bad mothers and neurotic men. Instead, this is a tale of regular folk, contradictory as hell, just like most of us. In the end, you can substitute AIDS for any crisis that might visit a family, and the windswept shores of Ireland for your own backyard. Because this is a story of the kind of people who rarely get to be the heroes of novels. They show themselves, when their story is told right, to fit the role just fine.

— Mary Elizabeth Williams

I Loved You All

By Paula Sharp

Hyperion, 384 pages

Barely three pages into Paula Sharp’s new novel, the realization crept in: that I might be holding the next Oprah book in my hands, and that to my horror I was unabashedly enjoying it. But it’s probably not fair to succumb to my own literary snobbishness and put down Oprah’s efforts. And it’s definitely not right to taint Sharp’s book, though it does contain many of the elements — first-person narration, an exotic character name, a Southern female character who leans heavily on her eccentricities — that seem to guarantee an author a flight to Chicago for a chat with the Club.

“I Loved You All” is the story of the Daigle/Molineaux family, by their own description “displaced characters,” transplanted by circumstance from their native New Orleans to the cold climate of a remote upstate New York town whose main business is its state prison. Two sisters, 8-year-old hellion Penny (“Penny has a piece missing,” says one of her teachers. “It’s what other people call a conscience”) and 15-year-old conformist Mahalia (who thinks that the world “should behave the way she [wants] it to because she did what she was told”), are being raised in the turbulent wake of their alcoholic mother, Marguerite.

In the summer of 1977, Marguerite’s drinking problem finally reaches a crisis. She is sent to dry out at a Louisiana clinic, and Penny and Mahalia are watched over by Isabel Flood, a neighbor whose rigid, ascetic ways contrast starkly with Marguerite’s permissive mothering. Isabel is Penny’s worst nightmare and, at first glance, the soul mate Mahalia has been waiting for. Soon Mahalia is drawn into Isabel’s evangelical right-to-life world. When Marguerite returns she finds that in the course of a few weeks her family may have changed forever.

Sharp manages to construct deep characters and complex relations with just a few sentences — the sign of a natural storyteller. And she does not shy away from difficult subjects. She portrays the right-to-lifers of the small prison town in a well-balanced, almost loving manner. As Penny’s uncle says of these virulent souls, “the worst things people ever do, they do because they believe they’re fighting what’s wrong. In that way, good introduces evil back into the world and the circle is complete.” That’s what this novel is: complete. Not flawless, but a well-drawn, satisfying circle.

— Ed Neuert

Troublemaker

By Brian Pera

St. Martin’s, 214 pages

Earl, the 22-year-old homeless, gay, trick-turning, drugged-up narrator of Brian Pera’s fine first novel, exists in a state of dim, vaguely discerned longing and expectation — speaking, thinking and perceiving in a mumbled Ozark patois so thickly uneducated that the journal Kirkus Reviews, before the book’s publication, described Pera’s hero as “retarded.” It was news to Pera, who says “Troublemaker” was partly inspired by “Huckleberry Finn” and who detects “an Easterner’s take on a Southerner’s dialect” in the knee-jerk assumption of mental deficiency.

“That’s the crux of the book,” Pera observes. “It’s all about Earl being inarticulate.” It’s also about Earl being lost, abused, exploited, obsessed and driven from pillar to post in a fractured bildungsroman that’s all voice, texture and dulled sensibility. A steady, deadpan humor infuses Pera’s portrait of a born outcast — “just one steady blur of nothing much,” as Earl describes what goes on in his head: “Just flickers of things, and so slow seemed like they couldn’t hurt a flea on their way in or out … None of it fit together any better than it ever done, all of it just as jumbled as always. But floating, just free-floating, and didn’t make no difference to me no more anyways.”

At first you think the voice will overwhelm you, but Pera pulls it off: Earl’s language has a stubborn integrity and innocence and a repetitiveness that quickly become reassuring, hypnotic, as he wanders from Omaha, Neb., to Arkansas to New York and Memphis, Tenn. (where Pera lives), seeking just to get by, to find something to eat, a place to stay, some dope and — could it be? — some affection for himself. Pera writes straight from Earl’s brain, jumping from time to time and place to place, explaining nothing, revealing nothing about Earl, his actions or motivation, until Earl himself happens to think of it. Earl’s father has died; his mother kicks him out of the house, as do both his grandmothers, a New York madam, his Aunt Edna and a string of “johns” who expect and want from him only what they contract to pay for.

“The john laid out on the couch behind me and pulled at my shoulder for me to join him,” Pera writes. “‘I like to lay together like spoons,’ he said, which was more or less okay by me, since that way I could turn my back to him and make whatever kind of face I wanted.” Earl’s obsessive desire to connect emotionally with a fellow hustler, Red, drives “Troublemaker” in fits and circles to its final destination, at the Garden of the Gods in Colorado Springs, Colo., where Earl both finds and loses what he’s looking for. To tell more would spoil both the journey and the point. This is a superb debut.

— Peter Kurth