The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs knows exactly how many men served in Vietnam (2,594,200) and how many were killed in action (58,188). It can furnish all kinds of stats about those soldiers, like the percentage of men who worked in supply (between 60 and 70 percent) as opposed to combat (30 to 40 percent). But ask about the women who served in Vietnam — women other than nurses — and the numbers disappear. The records are muddled, they say; the files don’t work that way. Yes, the armed forces sent women to Vietnam, but an official record of their presence there doesn’t really exist.

At least 1,200 female soldiers were stationed in Vietnam in various branches of the military as photojournalists, clerks, typists, intelligence officers, translators, flight controllers, even band leaders. They served prominently in Saigon, in the Mekong Delta and at Long Binh, which was, for a time, the largest Army headquarters in the world.

They could not fight, nor were they allowed to carry weapons to defend themselves. Most were part of the pioneering Women’s Army Corps (WAC), created in 1942 to integrate the armed forces. All of them enlisted for service in Vietnam, mostly in the early part of the war.

Like a lot of Vietnam veterans, these women have been dogged by their experiences in country; unlike many veterans, they do not feel officially recognized and have been reluctant to seek help. Some have been plagued by symptoms of post-traumatic stress syndrome and exposure to chemicals. Others have harbored the fact of their service like a shameful secret.

“For eight years, my husband didn’t know I was a vet,” says Agnes Feak, who participated in an air evacuation of Amerasian children called Operation Baby Lift. “I kept my mouth shut when I came home. He found a photo of me in fatigues and said, ‘Who’s that?’ And I said, ‘That’s me.'”

Linda Watson, who was a private first class, says, “I didn’t think I qualified for benefits, because I didn’t consider myself a Vietnam vet. It’s just recently I came to the realization I am. I didn’t see all the atrocities. But I saw enough for me.”

This week, the WAC women who served in Vietnam are having their first reunion, a three-day “homecoming” in Olympia, Wash. For some of them, it will be the first time they have talked about the war. Some won’t go, because they still can’t.

“I’m looking forward to [the reunion] with trepidation,” says Karen Offutt, who served as an administrator in Vietnam. “I don’t know what memories will come out. On the other hand, I’m hoping that it will put closure to it.

“People keep saying, Why don’t you forget Vietnam? I don’t think I’ll forget Vietnam, because it changed my trust in people — it isolated me. I seem like a very sociable person. But I’m very much a recluse. It just changed me. The babies that I took care of — babies with their legs blown off and shrapnel wounds, I felt so helpless and the guilt of having seen what I had.

“I’d like to forget about it, but I think about it every day.”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

[Editor’s note: Reporter Austin Bunn conducted dozens of interviews with WAC veterans of Vietnam for Salon Mothers Who Think. Their memories and reflections follow.]

+ ARRIVAL IN VIETNAM

Name: Marion C. Crawford

In country: Tan Son Nuht, Long Binh, October 1966 to June 1968

Rank: First sergeant, in charge of all enlisted personnel (works with commander)

Age in Vietnam: 36

Current age: 69

Current home: Eustis, Fla.

When I first got there, it was like nothing I had ever experienced. The minute the plane went nosing into the airport in Tan Son Nhut — they have to come in at such a steep angle because of ground fire — we were hanging on by our toenails. It was a real quick landing with a jerk stop.

When I first got there, it was like nothing I had ever experienced. The minute the plane went nosing into the airport in Tan Son Nhut — they have to come in at such a steep angle because of ground fire — we were hanging on by our toenails. It was a real quick landing with a jerk stop.

When you got out of the plane, it was all guys with heavy weapons walking around. And, of course, I was a novelty being a female soldier with a diamond [for sergeant] on my arm. All the guys looked at me and said, “She’s got a diamond, that means there are women coming!” And they all kept yelling at me, “When are the women coming? When are the women coming?” I laughed.

That’s one of the reasons why there was a fence around the WAC detachment, because there were 50,000 guys and I was getting in 109 women.

Name: Karen Offutt

In country: Long Binh, Saigon, July 1969 to June 1970

Rank: E5

Age in Vietnam: 19

Job: Stenographer, office of the chief of staff

Current age: 50

Current home: Wesley Chapel, Fla.

I didn’t have a clue about where Southeast Asia was. When I got off the plane, these guys were cheering and I thought they were cheering for us. But then I looked at them and I realized they were cheering because they were getting to leave. They looked just so old. It was depressing.

I didn’t have a clue about where Southeast Asia was. When I got off the plane, these guys were cheering and I thought they were cheering for us. But then I looked at them and I realized they were cheering because they were getting to leave. They looked just so old. It was depressing.

They put me on this bus and I thought I was going to Saigon, but I went to Long Binh [Army headquarters]. On the bus, there was chicken wire on the window and I asked the guy next to me and he mumbled something. And I said, “What’s that?” And he said it was to deflect the grenades. And I just thought, Oh, my God. I looked back at the plane to see if I could get back on it.

My first night they started hitting us with mortar rounds. The whole building shook. It was a horrible night. I just laid there. I was paralyzed. And I figured I wasn’t going to make it out. There were four or five of us in the room. And they were saying don’t worry about it — the Vietnamese are bad shots. I thought, Yeah, right.

+ LIFE IN LONG BINH

Name: Precilla Wilkewitz

In country: Long Binh, January 1968 to September 1969

Rank: E5

Job: Administrative assistant for U.S. Army Vietnam (USARV) inspector general’s office

Age in Vietnam: 19

Current Age: 51

Current Home: Zachary, La.

They didn’t issue us weapons in Vietnam. At basic training in Fort Benning, Ga., we trained with M-16s, M-14s. We had to do marksmanship and be in foxholes and we had to do mounted and dismounted attacks. But they didn’t issue women weapons [in country].

They didn’t issue us weapons in Vietnam. At basic training in Fort Benning, Ga., we trained with M-16s, M-14s. We had to do marksmanship and be in foxholes and we had to do mounted and dismounted attacks. But they didn’t issue women weapons [in country].

One night we had a human mass attack on all four corners at Long Binh. We had mortar attacks that could have landed on our compound and killed all of us. Did we have anything to protect us? No, all we had was prayer. And I did a lot of that.

Name: Claire Starnes (the organizer of the reunion)

In country: Long Binh, February to July 1969; Saigon, July 1969 to February 1971

Rank: Staff sergeant (E6)

Age in Vietnam: 25

Job: Translator, Army Engineer Construction Agency Vietnam (USAECAV); photojournalist, Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) Observer newspaper

Current age: 55

Current home: Conowingo, Md.

The biggest fear was to be taken prisoner. Can you imagine what kind of nightmare in terms of public relations it would have been? What a coup for the NV? Apparently in 1968 military intelligence had gotten a document off a North Vietnamese that they were offering a $25,000 reward for a white American female. Our own government gave us life insurance which was worth only $10,000. We laughed about it, because, boy, we were worth more to the NV.

The biggest fear was to be taken prisoner. Can you imagine what kind of nightmare in terms of public relations it would have been? What a coup for the NV? Apparently in 1968 military intelligence had gotten a document off a North Vietnamese that they were offering a $25,000 reward for a white American female. Our own government gave us life insurance which was worth only $10,000. We laughed about it, because, boy, we were worth more to the NV.

Precilla Wilkewitz: All women had to eat at the 24th Evac Hospital. So when we went there we had to eat with the patients. Some of them had missing arms, legs, eyes, and had IVs sticking out and all these little gadgets hanging from that walking thing.

There were only two redheads there in the first place. And I would sit down with the patients and they would start crying. And many, many of them asked me if they could touch my hair, because they saw very few round-eyes and everybody who was there had an aunt or a friend or schoolmate who was redheaded.

It was so traumatic that I quit going. I don’t think I ate 20 times in the mess hall because they would cry. How can you sit there and eat while these soldiers are crying?

+ WORK

Name: Priscilla Mosby

In country: Long Binh, Mekong Delta, March to June 1970, August 1971 to April 1972

Rank: E4

Job: Stenographer, bandleader

Age in Vietnam: 20

Current age: 48

Current home: Cleveland, Ohio

In Vietnam, first they had the USO tour shows coming through, but they weren’t cutting it because they only would send them so far into the bush. So they tried a command military touring show which consisted of all military personnel that could go out and entertain the troops and build the morale.

In Vietnam, first they had the USO tour shows coming through, but they weren’t cutting it because they only would send them so far into the bush. So they tried a command military touring show which consisted of all military personnel that could go out and entertain the troops and build the morale.

So I went to Saigon and auditioned. I sing and play the keyboards. I used to go down to Louisville and volunteer to sing at the churches — gospel singing was my hobby. [In Saigon], I sang “Summertime” [at the audition] and I had to do it a cappella. When I opened my eyes, I asked the gentleman who was overseeing the program, “Did I pass?” and he said, “Lord, yes.” He told me, “I’m going to put you together a really good band.”

I had a nine-piece band, one helluva band. There was this singer named Johnny Taylor who made “Who’s Making Love.” His lead guitarist was my guitar player. My organist, he played for James Cleveland in the Angelic Choir. My sax player was a guy named Danny Hall, he played with a group named Cold Blood. He was very versatile.

We wrote most all of the songs — love songs, country, jazz, ballads. We did Frank Sinatra and Barbra Streisand, because I never knew where I was going to go — and there was no guarantee that it was going to be a predominately minority crowd. My first band was called “Phase 3,” because there are four phases before you die. If you’re out in the field, you’re in phase 3. You’re hanging on — you may make it and you may not.

I went from the Mekong Delta and DMZ [the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam]. I played fire bases. I had to sign a disclaimer because I was a female and I wasn’t supposed to be out of Long Binh. I stayed out in the field for eight months.

Half the time we couldn’t hook up the electrical instruments that we had, because there was no electricity. So we had to just rough it, and that was even more fun. I was the show leader and I said, “The show must go on.” If you played bass, you would stand up there and go “Da-Dom-Dom-Dom” and make the sound with your mouth. It was beautiful.

We performed for three hours. I was the only female out there in the field. We had some wild times. The main thing I kept in mind was to be decent and dedicated and determined and to let them know that it was going to be all right. They could let off steam, singing and dancing and pouring beer on me, whatever — [my bottom line was] just don’t rape me. And nobody tried.

The American Consulate was using us for all kinds of experimental things, trying to develop a diplomatic friendliness between the countries. We did some music for Vietnamese soap operas over there and our role was … the music. It was strange — I didn’t understand a word they were saying.

[Then], we were in Bihn Thuy which is in Mekong Delta. I was in the little city Bien Simoa, where I was doing some shopping. I heard that we were getting hit. When there is incoming you know — bombs are flying and people are running and scrambling. I knew it was going to be a little dangerous to walk right into the firefight. I took refuge in a restaurant. I went through the procedure of coming out of military clothes — stripping down to my pants. I took my top shirt off and tied it around my waist. I had my T-shirt on. They had black people over there [who were] Cambodian. And I could speak Vietnamese pretty well, so sometimes I could pass. That helped me.

I stayed there until my instincts told me to move. When I came out, I saw a couple of guys that I knew who were Navy SEALs and I went with them. It was like an unspoken procedure, and you just act like it’s no big deal.

So, I got back to the base and someone tells me that the bunker has been hit. My guys — the barracks they were in — were totally demolished. My entire band had been killed.

I remembered something that one of the guys told me and we laughed about it. He said, “If I ever croak, make sure they don’t cremate me because I don’t want to burn twice because I know I’m going to hell.” I thought about it and started laughing. I laughed. Someone said to me it’s not a laughing matter. But that’s the only way that I knew how to handle it.

Name: Doris I. “Lucki” Allen

In country: Long Binh, Saigon 1967 to 1970

Job: Intelligence, Army Operations Center

Rank: E7

Age in Vietnam: 40

Current age: “7thank you2”

Current home: Oakland, Calif.

I worked in the operations center. There were 300 men to every one women on the Long Binh post. Run that around in your mind.

I worked in the operations center. There were 300 men to every one women on the Long Binh post. Run that around in your mind.

I started [doing] intelligence analysis in USRV, the Army Operations Center. Every intelligence report, every information report that had to be written down from all over Vietnam, came across my desk. Usually they would throw them out. [The report] would say Charlie crossed the street last night. Another report, way down, would say Charlie walked down the street and he went into the third house … I was the one who sat there and said, “Hmm hmmm,” and put it together.

The reports would come in saying Allies had five killed and 20 wounded and three enemy killed and 81 wounded. Most of the time we did better than they did, because all you can say is I think I killed them. It got so bad that down in My Toh one of the commanders told his troops, “When you come back here you bring an ear and I will know that he’s dead.” And that’s when they started calling them “apricots” in order to prove that somebody had died.

I got there in October of 1967. Tet Offensive was January 30th of 1968. Thirty days prior to that happening, I turned in a report called “50,000 Chinese.” I knew a major offensive was coming from all that I had read. There couldn’t have been that many Viet Cong in the world. The report was a page and half. I took it to my supervising officer and he said, “Take it to Saigon.” It was that important — he believed in me. I took it to Saigon. I took it to MACV (Military Assistance Command in Vietnam). I talked to the bigwigs. I was thinking, You better disseminate this. They said, “No. I don’t think we can do this.”

I asked myself why they weren’t listening. I just came up recently with the reason they didn’t believe me: They weren’t prepared for me. They didn’t know how to look beyond the WAC, black woman in military intelligence. I can’t blame them. I don’t feel bitter. That’s just people, baby. When you aren’t prepared for something, you just aren’t prepared.

I came back to the states with no guilt. I had sadness, I saw those names on the wall, but I kept doing my job.

+ WOMEN IN COMMAND

Name: Peggy E. Ready

In country: Tan Son Nhut, Long Binh, 1966 to 1969

Rank: First lieutenant

Job: first WAC commander of the first WAC detachment

Age in Vietnam: 29

Current age: 61

Current home: St. Augustine, Fla.

If a man had problems with me, I mostly ignored it. I tried not to take an abrasive approach to anything. But I do recall one funny incident when we were still down at Tan Son Nhut.

If a man had problems with me, I mostly ignored it. I tried not to take an abrasive approach to anything. But I do recall one funny incident when we were still down at Tan Son Nhut.

We were in a briefing with my commander’s staff one morning and they had come up with a plan for what everyone was supposed to do if we were under attack. Everybody had all these opportunities to go hide here or go do that, and what they wanted the women to do was rally around the flagpole in front of the headquarters.

So, I’m thinking, This is the most absurd thing I have ever heard in my life. The flagpole was right outside of headquarters. I let the S3 — the operations guy — go through his speech. When he finished, I raised my hand and said, “I really don’t know much about tactics and strategy of war, but if it would seem that if the enemy were trying to get our headquarters, they would aim right at the flagpole, no?”

People just started falling out of their chairs, laughing. And he turned beet red. He had not thought of that. And the next day, they started building the first sandbag bunker for us women.

Karen Offutt: I remember feeling like I should be out there fighting. I really wished that they would have let us, even though I guess there are some problems about women and men fighting. I felt guilty about that.

Towards the end, I felt something snapped in my head. We worked 12-to-15-hour days. We didn’t get a lot of time off. I remember they called us in for special times at night after we worked all day. One day they were giving the dictation about where they were going to hit that night. It hit me right then that I was helping to kill people. And I started thinking about how many villagers, how many kids would be killed that night. And I started having a lot of conflicts.

I worked for several generals — they just treated me like a daughter. One was especially concerned — he would never let me ride with him. He would never get any hint of impropriety. The rest were pretty nice. I was a hard worker.

There were some people putting their arms around me. I was always such a weak little thing. I remember near the end this one colonel put his arms around me and kept putting his arms around me and I spun around and said, “I’ll knock you flat if you do that again.” I was 123 pounds! I didn’t put up with anything after I was there for a while.

+ RELATIONSHIPS IN VIETNAM

Name: Marilyn Roth

In country: Long Binh, April 1968 to April 1969

Rank: E4

Job: Clerk typist

Age in Vietnam: 25

Current age: 56

Current home: Melbourne, Fla.

“I weighed over 200 pounds and I had dates every night. Thank God I have the memories because I haven’t had a date in five years. I had a lot of action, because these guys didn’t care what you looked like as long as you had round eyes. They stood in line at my door.

“I weighed over 200 pounds and I had dates every night. Thank God I have the memories because I haven’t had a date in five years. I had a lot of action, because these guys didn’t care what you looked like as long as you had round eyes. They stood in line at my door.

I made everybody laugh. I was fat and bubbly. I had a wonderful time in Vietnam. I did. We partied every night. It was a year of just bliss for me. I had a great time. Best year of my life in Vietnam.

Karen Offutt: I was 19 when I went. I went over in July and came back [to the United States] in October because my grandfather passed away. When I came back [to Vietnam], I was an emotional wreck from the funeral. I was determined to live my life — all my poetry showed that I was thinking that I was going to die.

When I turned 20, I thought I had respected my parents’ wishes and that I had lived a moral life. I was introduced to somebody [in Saigon] and it turned out that that was the first person I was intimate with.

We had a dayroom across the hall from my room. It had a couch and a TV, I would go in there and do my tapes home for my parents. That’s where the dastardly deed was done. There wasn’t a lock on the door. It lasted two minutes. I waited 20 years for two minutes.

Then, a couple of weeks later, they told me that they had all lied to me, that he was married. So not only did I sleep with somebody, but it was a married somebody. And I was raised really Christian. It affected me really deeply. I felt that not only was I going to die in Vietnam, I was going to go to hell.

I found him four years ago and called him. He was a soldier and he’s now a deputy sheriff in Arizona. I just said, “Do you remember me? Do you remember that you took my virginity?” And he said, “Yeah.” And that was the end of the conversation basically. It was all a long time ago. I got some kind of closure.

Priscilla Mosby: One guy, Jessie Montague, he got killed on Valentine’s Day. That was in 1972. He and I were stationed together at Fort Knox before I went. When I volunteered to go, he decided that he was going to sign up to take care of me. He was a military police and he got a job as an escort with my band.

We were on our way back to Saigon, from the last show that I had done. I was going home in April and I wasn’t going to perform anymore. We were sitting around the camp and we wanted to bed down for the night because it was monsoon and it was raining so hard you couldn’t see anything.

We got under sniper fire — that’s when they just start shooting at you. Jessie put me in the bushes, in a rice paddy behind some bamboo shoots. He said, “Stay here.” And he gave me the .45 and said, “If you think you’re going to get captured, take this, and blow your brains out.” And I said, “Got it.”

I stayed there all night. I still have leech marks on my legs where they got me. I wasn’t going to say nothing. I know what happens when you open your mouth. A couple of times I heard splashes behind me. That was Viet Cong that somebody in our camp had spotted. And all I did I was pray, “Lord. Please. Help me.”

Eleven hours later, when all the smoke cleared, Jessie was the only one who got hit. He got killed from the sniper fire.

Name: Donna Loring

Rank: E2, E3, then E2

Location: Long Binh

In country: November 1967 to November 1968

Job: Communications center specialist

Age in Vietnam: 19

Current age: 51

Current home: Richmond, Maine

I had one real good friend, an Australian guy. The Australians had troops there, too. We would go out on our off-time — we would go to the NCO (non-commissioned officers club) and meet up. His name was Spook. He was reported killed in action. Somebody told me that.

I had one real good friend, an Australian guy. The Australians had troops there, too. We would go out on our off-time — we would go to the NCO (non-commissioned officers club) and meet up. His name was Spook. He was reported killed in action. Somebody told me that.

And then one night, a little after 10, somebody came in and said, “Spook’s outside and he really wants to see you.” And I went outside and the duty officer said, “You can’t go out there. I’m giving you a direct order you can’t go out there.” And I said, “I’m sorry. I have to go.” And so I went out. And he was there and I talked to him. And when I came back I got busted for that. I got demoted to E2.

+ COPING

Name: Camilla Wagner

In country: January 1968 to January 1969

Age in Vietnam: 25

Rank: Lieutenant, Women’s Air Force (WAF)

Job: Supply

Current age: 56

Current home: Lawrence, Kan.

“We were in a hotel over there in Saigon and almost all of them have a wall around them. A bus came around at 6:30 a.m. and picked everybody up. And as we were walking out of the gate toward the bus, somebody threw a grenade.

There were Chinese guards for our hotel and one of them was killed. I had three or four pieces of shrapnel in my leg, and some in my back. Not much, but if you’re wounded at all from enemy fire, you can get a Purple Heart. A lot of people ask about it, like, “Were you braving gunfire?” but it isn’t really that way.

Peggy Ready: I was in Saigon November through June, during Tet. It was scary. I learned real quick that you tried not to get in a crowd, and if you did, that you watched out for things like anybody who had anything in their hands. You don’t get near that person. If you’ve driving down the street, you never did anything so foolish as run over a crumpled bag, because too often it had a bomb in it.

And to this day I find myself, if I’m driving down the street, and there is trash on the road like a crumpled bag or a box, no matter how small, I will do with practically everything to get away from it, before I realize that it probably doesn’t have a bomb in it these days.

Name: Jeanne Bell

In country: Saigon, March 1968 to October 1969

Age in Vietnam: 19

Rank: E5

Job in Vietnam: Administrative services

Current age: 51

Current home: Thonotosassa, Fla.

I got there right after Tet. I had several incidents when I was afraid for my life. In Saigon, it was more of a psychological warfare — you never knew when you were going to get mortared.

One time, I was coming downstairs into the hotel lobby to get my ride to work. We took machine gun fire and everybody hit the floor. We just got into the elevator and went up to the eighth floor, because we didn’t have any weapons.

Another time, I left my office to go to lunch and we had two gray station wagons. I took one and left. I was about three blocks away when I heard an explosion. That’s not uncommon and you just look around and you kind of hit the gas and keep going. But shortly after I had left, the other station wagon had blown up. Somebody had planted plastics on it. The people in my office thought I was dead. When I came back, everybody was white-faced and they grabbed me and hugged me and they told me what happened.

+ OPERATION BABY LIFT

Name: Agnes Feak

In country: Tan Son Nhut Airport, 4 flights of Operation Baby Lift, April 1975

Age in Vietnam: 17

Rank: E4

Job: Nurse

Current age: 46

Current home: Jupiter, Fla.

Operation Baby Lift was a humanitarian project to get the Amerasian children out. This was the children of the American men. They had blue eyes and blond hair, plus you had African-American kids. If they stayed around in Vietnam, they would be murdered by the North Viet Cong.

They were in different orphanages in South Vietnam, run by Catholic South Vietnamese nurses. Usually the mothers put them there, or left them at the front door.

We flew into Saigon. You just did your job, which was to pull kids into the plane. They were just loading them as fast as we could so we could get the hell out of there. We were just grabbing kids. You felt shock. Civilians were grabbing the planes just to get out. We were called “lap holders.” The children were extremely young. We had to hold them during the flight.

We brought out 10,000 to 15,000 children. We estimate as many as 40,000 kids were left behind.

One flight went down. That one had Capt. Mary Klinker on it — she was the last nurse to die in Vietnam. The back door blew open and it crashed into the rice paddy. She was in the back and she blew out. Some people say it was sabotage. Some people say it was an accident. That was in April 1975. It was right when I started.

One baby, I don’t know if she survived, I’ll never forget her. She was so sick — so sick, we couldn’t get her fever down. And she just smiled. She had the most beautiful blue eyes. And she just smiled. She never cried. Sometimes she was so sick that I rocked her just to see if she was OK. She was 6 months old but she looked more like 3 months. She was undernourished.

Her little hands would cling to my uniform. When I had to hand her over to the doctors [in the United States], I left crying because I had gotten so attached to her. These kids were heroes. They went through hell. People have to understand, war is not John Wayne. It is about death, destruction and it means civilian death. These children were casualties.

+ COMING HOME

Claire Starnes: It was the trip from hell. There were some parts that I don’t remember because of the stress. I was in the northern part of Vietnam. I walked into the hotel and I was in the fatigues from the day before. Mama-san came up to me and said, “The chaplain’s downstairs.” And I knew just what it was. I went downstairs and I said to the chaplain, “My mother died, right?” And he said, “You need to leave right away, we’ve started the paperwork.”

I went up to headquarters and my roommate was packing my stuff. They told me that I had to get down to the International Airport in Saigon, which was in Tan Son Nhut. They said, “You’ll have time to change in Fort Travis when you get back to the States.” I’m two days now without showering.

So I get on the plane and now we’ve got a 22-hour flight. I get to Travis and they say your flight is leaving out of San Francisco. I say, “I’ve got to change,” and they say, “No, your bus is leaving.” I get to Frisco and they are holding the plane up. I haven’t slept, I was really tired. I looked like hell and probably smelled like hell too.

And now I’m in Frisco and now I’m running to the plane. And all of the sudden I hear, “Hey Sarge, how’s the war going, kill any babies lately?” And I looked back at these guys and I said, “Screw ’em.” I kept on going, but they kept following me. I saw the gate and they kept on and at that point, my blood was boiling. I said, “That’s it, I’ve had enough.” I turned around. I said, “You want a piece of me? Come on, let’s go.” The attendant at the gate, he’s yelling at me, he’s closing the doors and he’s yelling at me. So I headed straight for the door. I sat down and thought, “Jesus I don’t want to be here.”

And I sat down next to this girl, and I thought, “Oh, no.” We had the idea of what a peacenik looks like, and this girl had long, matty-type hair and she had large, horn-rimmed glasses and I thought, “She’s one of those hippies from Frisco.” But it turned out she was very interested in what was happening in Vietnam. But I thought, “I want to be back in Vietnam. There, you were on pins and needles all the time but at least you knew you had to be.” Here, we thought, “I’m home, I’m supposed to be safe.”

+ AFTERMATH

Marilyn Roth: I was Claire Starnes’ and Precilla’s roommate … [but] I have a lot of Vietnam that is blocked out. Precilla would tell me stories about things we used to do and places we used to go and I don’t remember anything.

I really didn’t think about Vietnam until much later in years. I just put it in the back of my mind. The only time I would mention Vietnam is when I was in uniform. And people would say, “How come you’re wearing a Vietnam patch?” And I would say, “Look at my records, I was in Vietnam.” And that would bring back some memories, but then I would forget until next time.

Precilla Wilkowitz: When I got back, I had lost 40 pounds by nerves and improper diet. My sister used to say, “You just ignore things.” Petty things didn’t mean anything to me. People would say to me, “Don’t you think [that woman’s] dress is short?” and I thought that was ignorant. I had been to Vietnam. Those were not things that you thought about. If you did not have hot water that night, that was not important.

What I couldn’t get over was color. In ‘Nam, everything was brown and dirty and there wasn’t any color. I came home for Christmas. And that first night when I came home, my mother found me asleep underneath the Christmas tree. Because of the lights. I couldn’t get enough.

Karen Offutt: I got married and the husband I married, he wouldn’t let me talk about Vietnam. He hated it because he had graduated from USC and he had orders for Vietnam, [but] he had a friend change them. I made him feel chicken and cowardly.

Nobody talked to me for all those years about Vietnam. It was until I divorced [my husband] in 1986. I had nightmares and I would wake up, sweating and fighting. I was always wounded or captured in my dreams, I guess it was to make up for the fact that I wasn’t a real soldier. Then I started having anxiety attacks.

Before Vietnam, I was a sociable person, and when I came back, I just didn’t want to socialize really. I didn’t talk about anything. I was different. I would go to the store and I would be dressed up and someone would drop a can and I would hit the floor. If I was in a dressing room and someone slammed the door, I screamed. I was totally humiliated.

I had twins 15 months after I married my husband. One was born with cancer of the kidney and one was born with ADHD (attention deficient hyperactivity disorder). As soon as he could walk, he was diagnosed. He had some bone defects too. Then I had a daughter who had epilepsy.

In the late ’70s, I went to a meeting they had in town for the Veterans of Foreign Wars. They were talking about all their kids’ birth defects. And this one guy was talking about Agent Orange sprayings. And I said, “My kids are all messed up but it’s not from Agent Orange because I was in Saigon.”

He pulled out this aerial spraying map and he said, “Where were you?” I showed him. And he said, “Which year?” And I told him. He said, “That was the heaviest spraying year in the war in the area you were in.” Many of us have memories of them spraying overhead and by trucks in the road, but it’s just a hazy thing.

I don’t know hardly anybody who doesn’t have cancer. One of my friends was a nurse in Pleiku — she had stomach cancer, thyroid cancer, breast cancer and breasts removed. She has it in her liver now.

My twins are 27 now. My son was just here from Oregon and we talked about it. I have these lumps on my body that just appear sometimes — and he was showing me on his chest and under his arm where he has those too. My daughter and other son have them as well. I’ve had 11 pre-malignant polyps removed out of my colon. I’ve had two breast lumps that they’ve removed. I’ve got four more they are following right now.

My grandmother is 92 and is still really healthy and my parents are like Jack LaLanne. They are still working a three-and-a-half-acre place in California. They all live until their 90s.

Doris Allen: Good God. I still dream about [Vietnam]. I have PTSD — post-traumatic stress disorder. I have trouble in crowded situations. I used to go to the jazz festivals. I can’t go now. I don’t go where there are a lot of people like that. I can’t do that. The noises trigger it. I get nervous. Something in me just turns over in a big fear sort of thing. I still hit the floor sometimes when I hear loud bangs. And I have nightmares. I’m getting a little bit over that. I’m jumpy.

Jeanne Bell: I was married to a Vietnam vet. But we never talked about Vietnam. We were stationed in the same place, married for 14 years, but we never talked about Vietnam.

When we first came back from Vietnam, all we wanted to do was blend in, because people didn’t understand. People called me “baby killer” and people hated the soldiers. It was not a good thing to talk about. There was a lot of rioting. You just didn’t talk about it. When you did talk about it, I used to think about it sometimes at night and I would get very depressed and I would actually cry. I had some mementos that I would look at. So you tried not to think about it more than you absolutely had to.

I used to talk to my dad about it. I knew and understood from him, that when you serve your country, especially in a war zone, there are a lot of unpleasant things that happen and you deal with it the best you can. I didn’t know that they had a name for it.

Today I have counseling and I take medication. Today I have control. But for a lot of years, I lost jobs. I had uncontrollable anger. I would have flashbacks.

When I got so sick. I was already divorced from my husband. But I went to see him and told him what was going on and asked him if he had it too and he said, “Yes.” We sat and talked about it. That was like 18 years after we came back. There were a lot of forces in our marriage that were beyond our control. It was the first time that we had talked about having flashbacks.

+ ADOPTING

Name: Kathy Oatman

In country: Long Binh, February 1969 to May 1972

Rank: E6

Age in Vietnam: 35

Job in Vietnam: Senior administrative sergeant in data processing unit

Current age: 63

Current home: St. Petersburg, Fla.

Most of the groups over there sponsored an orphanage one way or another. And we went into the Tam Mai orphanage. It was a little town. It was right off of Ben Wai Air Force Base.

Most of the groups over there sponsored an orphanage one way or another. And we went into the Tam Mai orphanage. It was a little town. It was right off of Ben Wai Air Force Base.

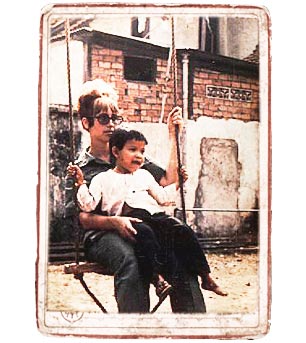

I got attached to one little boy there and I started paying a lot of attention to him. One day we had a staff picnic at the barracks, and we’d go out and get the kids and keep them there in the barracks with us for the day. When it became time for them to go home, my commanding officer asked me, “What are you going to do about Kevin? If you don’t get started you won’t be able to get that baby out of country.”

So I went to work on getting the paperwork going. I got him out of the orphanage and he stayed with me at the barracks for about a month. The orderly room would babysit while I went to work — the rest of the time he was in my room. I always laugh about it because when I had him at Long Binh and I would take him out at night, the other [women] in the barracks would say, “Get him out of the night air.” And if I didn’t take him out, they would say to me, “Take him out. Quit keeping that baby locked up.” He had so many mothers it wasn’t funny.

Then I decided I didn’t want to raise him by himself, so I thought, “I’ll have to go find me another one.” I come from a big family myself and I just couldn’t imagine a kid being raised on its own. I went to World Vision and I found my daughter there, Kimmy. They had a little hospital there. The Vietnamese government would bring their babies with medical problems to World Visions to get help. [But] the orphanages would try to take them back when it came time, [because] the Vietnamese government paid the orphanages by [the number of children they had in their charge].

Well, when I decided on Kim, I asked one of the ladies who worked there, “What are we going to do? When they come to take her back to the orphanage, I’m not going to get her back?” … So I found a Vietnamese lawyer who could speak English, and I got the paperwork and I let him take over. He got the birth certificate and everything. The military changed the rules real quick after that, changed the policy on single parents adopting kids while you’re in the military. Now, you can’t do it.

I extended my time by another six months because it took a while to get this done. So my next step was to go to the American Consulate and get them on the visa list. If I had been married, they could have immediately left country as soon as their paperwork was finished. But because I was single, they had to wait for a visa … I was frustrated.

When I went in with Kevin, to get him on the list, [the vice consul] just fussed over him and she thought it was wonderful that I was doing this. I went back in and said, “I’m taking another one.” And she couldn’t believe it. But what I found out later is that she put Kimmy on the list at the same time she put Kevin. It was so they could leave the country at the same time.

Kevin is now 30 and Kim is 29. I used to wonder about [whether] either of my kids had any desire to go back [to Vietnam]. In the town we used to live in, there was a little Vietnamese lady who used to run the alterations shop. And Kim went in there the one day, and the lady asked her if she ever wanted to see her real mother. And she pointed out to the car to me, and said, “That’s my real mother. That’s the only mother I know.” So I realized I didn’t have anything to worry about.