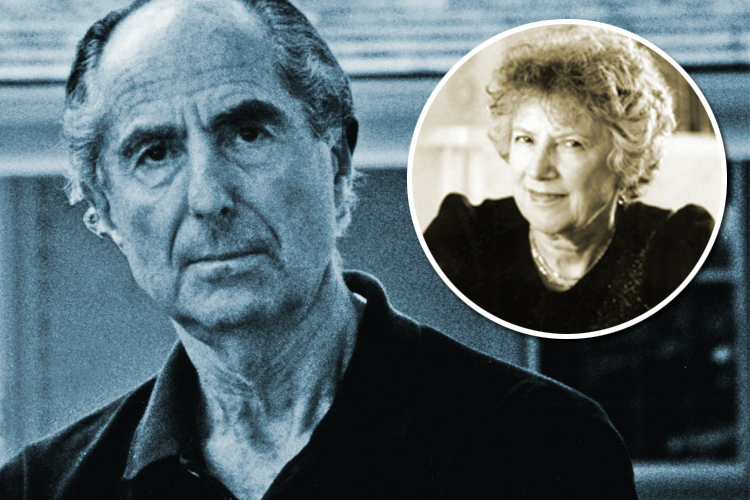

Last week, Carmen Callil resigned as a judge for the Man Booker International Prize because she disagreed with the other two judges’ choice for the winner: Philip Roth. The prize, which is awarded every two years, commends a single author for a body of work making an “overall contribution to fiction on the world stage.” When she announced her departure, Callil was reported saying of Roth that she didn’t “rate him as a writer at all” and that “he goes on and on and on about the same subject in almost every single book. It’s as though he’s sitting on your face and you can’t breathe.”

It took Callil a few days to present a fuller explanation. In the meantime, it was fascinating to watch various commenters respond to the kerfuffle. “I’m discouraged by what I assume is her ideologically inspired illiteracy,” Wendy Kaminer assumed for the Atlantic Online. “Is there a terrible scar of monotonous male sexuality in these inventions that limits their power or makes Roth deserve Callil’s dismissal?” fulminated Jonathan Jones in the Guardian. “To claim that,” he went on, “is to misunderstand what a novel is.” Eileen Battersby, in the Irish Times, sniffed, “The sexism and ego of Roth can certainly offend, and obviously bothers the irate Booker judge Carmen Callil.”

Not so obviously, in fact. Nothing in Callil’s initial statements about the affair indicated that her opposition to Roth’s work had anything to do with sexism or raunch. When she published a full account of her objections in the Guardian on Saturday, she expanded on a complaint that she’d mentioned from the start: Roth is the second North American (after Alice Munro) to receive the prize in its four-year history. Given that this variation on the Booker Prize is labeled “International,” and that it provides an additional grant that the winner may use to fund further English-language translations of his or her work, Callil had hoped that it would go to a less usual suspect.

She also doesn’t like Roth’s work very much, as she made abundantly clear. For the record, while I’m more or less in Callil’s camp when it comes to Roth’s fiction (particularly the face-sitting bit), her first remarks were thoughtless and high-handed. Perhaps Callil believed she was acting in the hallowed tradition of British literary prize judges who have aired their dirty laundry in the press, but insulting an author (any author) by name in such a context is uncalled for. There are enough readers who love Roth’s work to make him a reasonable choice for an important award, even if Callil can’t personally endorse that choice.

However, the really interesting aspect of the story is the straw woman erected by pro-Roth commenters like Kaminer, Jones and Battersby (among others) before Callil explained herself at length: the dour feminist scold who’s incapable of separating art from “ideology.” Instead, it turned out that Callil finds Roth’s fiction “narrow. Not in the Austen, Bellow or Updike sense, because they use a narrow canvas to convey the widest concepts and ideas. Roth digs brilliantly into himself, but little else is there. His self-involvement and self-regard restrict him as a novelist.”

These are legitimate aesthetic reservations, even if not everyone agrees with them. Yet if you do agree with them, and you happen to be a woman, chances are excellent that — no matter what you say — Roth proponents will assume your aversion is based in politics. This is as frustrating as telling the chef you don’t care for lamb chops and getting a self-righteous lecture on his supplier’s humane farming practices.

As recently as 30 years ago, subjecting a work of art to a political litmus test — is it racist, sexist, classist, homophobic? — was considered the supreme critical method, but fortunately times have changed. Unfortunately, they have changed with a vengeance. Now, in many circles, critiques that can be labeled as “politically correct” can also be summarily dismissed as “not literary arguments but emotional or ideological ones,” to quote Kaminer.

Presumably, literary arguments can also sometimes be emotional and ideological (this one certainly is!), but the point seems to be that if you’re a female reader who hates Roth novels, you must be motivated by (irrational) passion and doctrinaire political animus, whether you realize it or not. Your taste could not possibly arise from anything but “illiteracy” and an inability to understand “what a novel is.” Patronizing? You bet. Why, it’s enough to turn a girl into a feminist.

Further reading

Judge withdraws over Philip Roth’s Booker win: The initial story in the Guardian

Wendy Kaminer’s appreciation of Philip Roth in the Atlantic Online

Jonathan Jones on why Philip Roth deserves the Man Booker International Prize

Eileen Battersby defends Philip Roth in the Irish Times

Carmen Callil on why she resigned from the Man Booker International panel