In her late twenties, Sophie Fontanel decided to stop having sex. This wasn’t a typical case of a young heterosexual woman renouncing the opposite sex after a bad breakup only to reactivate her OKCupid profile a couple months later. Her abstinence lasted for over a decade. Twelve whole years, to be exact.

She chronicles these sexless years in “The Art of Sleeping Alone,” a memoir originally published two years ago in French. Fontanel’s reasons for abstaining are never explicitly spelled out. She vaguely references the previous “matchless scouring performed by sex.” In the opening chapter, she explains, “I’d had it with being taken and rattled around. I’d had it with handing myself over. I’d said yes too much. I hadn’t taken into account the tranqility that my body required.” There is also a disturbing encounter at the age of 13 with a man 20 years her senior who doesn’t heed her request to stop. She doesn’t explicitly call the encounter a sexual assault, but it certainly reads as one.

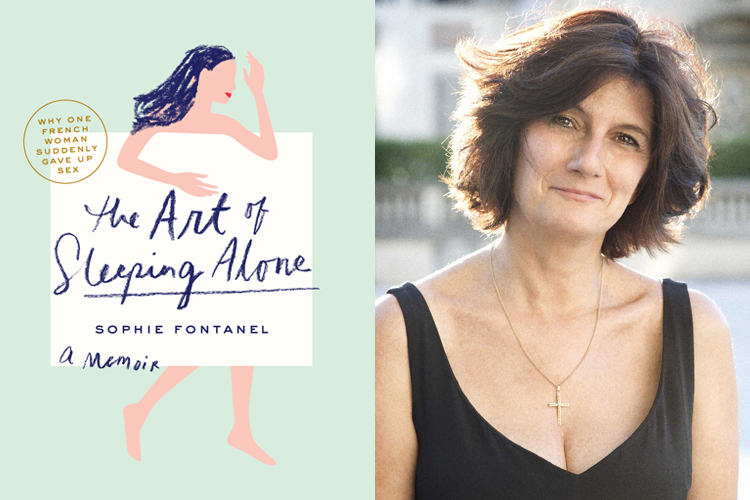

The book’s title and Crayola-esque coverscript suggest that it is prescriptive chick lit, a cultural polemic wrapped in pastels. I fully expected to encounter self-righteous prudery and an air of ascetic superiority. “The Art of Sleeping Alone” is surprisingly lacking in advice and judgments, though — and that is to its great credit. Instead, the book reads as a series of literary vignettes in which Fontanel finds herself the only single person at dinner parties and getaways with friends. She constantly encounters people’s questioning confusion over her celibacy and their ultimate disapproval and even anger toward it. “If there was a party, everyone in turn would come sit next to me to regale me with how he or she thought I should live and what I deserved to have,” she writes. “What it boiled down to was that I should live like them.”

Instead of trying to fix her, some friends fetishized her. An old pal admitted to her that she and her husband fantasized about having a threesome wth her, aroused in large part by imagining her “modesty” and “timid refusal.” Others tried to diagnose her problem: A good male friend questioned whether she might be gay. A female friend came on to her, because, as Fontanel writes, “She had thought that since I wasn’t seeing men anymore, I would go for a woman.” The real trick is that Fontanel manages to write about these travails of sexless singledom without coming off as a kicky chick-lit heroine or self-mocking Bridget Jones.

It’s easy to notice all of the ways that sex is proscribed and restricted, but Fontanel shows the other, less acknowledged extreme. She writes about listening to a radio program in which a doctor insists that “the more someone makes love, the better that person will become in every domain.” Upon hearing this, she says, “I cracked up.” Fontanel calls in to the show to argue, “No word can encompass the absence of a sex life for people who are simply waiting hopefully. We say ‘chastity’; that’s not the right word. We say ‘abstinence’; that’s not the right word. ‘Asexuality’ is not the right word. So stop. Enough of this nonsense.”

I called Fontanel while she vacationed in Greece to talk about the taboo of sexlessness, the erotics of abstinence and what American women have to learn from the French.

You don’t say in the book exactly how long you went without sex. Why did you withhold that?

What a good question, you are the first person who has asked that question. Even if I have talked about some very private facts about my life, I’m a very shy person. I thought that some things could remain private, but I was wrong. As soon as the book was published, everybody had that question. In the book, I kept the silence because I had that hope that nobody would ask.

Going into it did you have a goal of remaining abstinent for a certain number of years?

I hadn’t decided anything. I remember I was 27 years old, and I had begun sexual activity very young, and I said to myself, “Am I happy, sexually?” And my answer was “no,” even when I took pleasure. I decided to wait for something better, and for me something better was supposed to come very soon, you know? It was impossible to imagine such a long time. But now, when I’m looking back, it was nothing, those 12 years.

What were you waiting for?

I was not waiting for love. I think it’s a mistake to think that women are always expecting love. We are expecting to be in good hands, even if these good hands are just for two nights or one week. We’re waiting as in the movie “Out of Africa.” We are waiting for a man, maybe his presence will be rare, but it will be a high quality of presence. So I was waiting for something ecstatic.

Why is sexlessness so taboo — especially in a culture in which sex itself can be such a taboo?

We have put sex in a too high position. Of course, for me, the fact of making love in a very good way is incredible, it’s a very good thing, but the idea that the sexual life, that making love regularly is a good thing, for me it’s not true. Sometimes, making love just once, if it’s good, it’s better than making love every day.

Your book has been very differently packaged for sale in the U.S. The title makes it sound like it will be prescriptive. What do you make of the changed title, the new cover for American audiences?

When the decision was made to publish my book in the United States, the title was supposed to be “How to Sleep Alone,” as a guide. It was my idea to add in “the art of” because to me it’s a beautiful thing. I’m not against love or sexual activity but when you sleep alone usually you are complaining about the fact that you are sleeping alone. For me, the first thing you have to do is consider it as an art. In French, the title of my book was, “The Desire.” It’s interesting, because my book seems to be about a lack of desire, but it’s not. It’s about a very big desire, a desire too big for reality.

I noticed that in promotional materials for the book, emphasis is being placed on your being French, and that seems shrewd given the success of “French Women Don’t Get Fat” and the like. Why do American women feel they have something to learn from French women?

First of all you have to learn about me not because I am French but because I am a writer and a very original person, you know? I have learned how to live my own way. The social norms don’t count for me. After that, indeed, I’m French and I’m a very, very French person. The way I dress — my clothes are very French. I was in L.A. last summer and everyone stopped me in the street to say, “You are French!” That’s important, because if you are French, you’re supposed to be well-dressed, well-educated and a very good lover.

What place does sex have in your life now?

After my long-time [celibacy], I met a man and I had a boyfriend for years, but now I’m alone. For me, being alone is not a question. For me, I’m not thinking, “Oh, I am 50 years old, am I young enough to meet a man?” I don’t know what it is to think this way. For me, being alone is freedom. It’s not as if I was walking in the streets and looking at all these handsome men and thinking, “Oh no, they don’t look at me!” I don’t see handsome men. Charming men I don’t see, where are they? It’s very, very rare, so I have made up my mind. I’m sure that because it’s rare you have to live between the love stories.

What did your sexlessness change for you? How did it change you?

It was very important. It has opened my eyes. At the beginning I thought that married people were happy together having sex. I was considering my celibacy as an illness. During all those years I talked to a lot of people and I learned that sometimes when you’re in a couple you don’t make love at all. Sometimes when you’re alone you have a very big libido in your mind; sometimes it’s more rich in your mind than in the real-life bedrooms of married couples. Sometimes my friends with boyfriends were less happy than me. Of course they had someone in their bed, but there was a price to pay, you know? My mother used to say that there’s a price to pay for everything. You don’t want to be with a boring man, so the price to pay is to be alone. I think that married people are very big liars, because if they don’t lie to say that they are happy sexually then they are ridiculous. So when a married couple is next to a single person, it seems that it is the single person who is the more pitiful, but maybe that’s not the case.