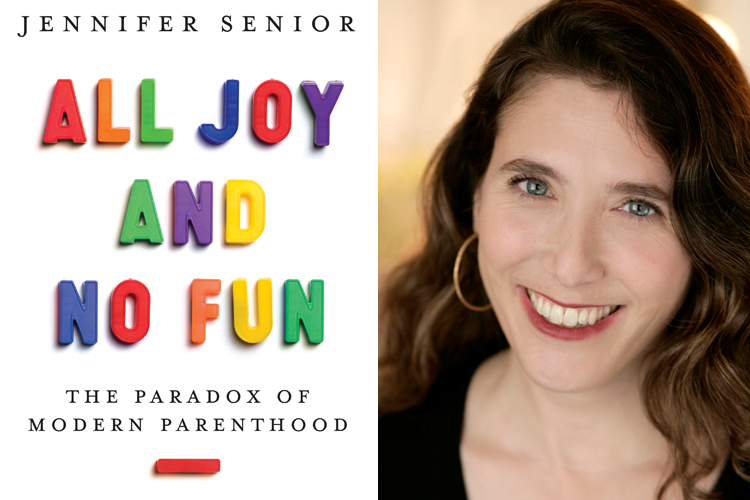

Jennifer Senior made a splash in 2010 with a New York magazine story provocatively titled, “Why Parents Hate Parenting.” In it she dropped the bombshell (or non-bombshell, depending on whom you talk to) that many parents don’t actually find taking care of kids particularly fun: A now-famous study found that moms ranked it as less pleasurable than housework. She expands on that sobering thesis in the just-released “All Joy and No Fun,” which follows a variety of middle-class American parents to find out what makes raising kids so stressful — and why people do it anyway.

Senior makes a persuasive case that middle-class children have been placed in a strange and unprecedented social position: at the top of the family hierarchy, with no responsibilities of their own. This position leaves parents overextended and may even make kids unhappy — though as Senior explains, explicitly trying to raise a “happy” child may be a fool’s errand.

At the same time, she notes that the news may not be all bad — or, rather, that the way social scientists study parenting may be ill-equipped to deliver good news. As her title suggests, the parents she talks to experience moments of transcendent joy. And their kids also provide them with moments of hilarity and introspection, as when one boy asked his father, “Can you break water?” (or when another boy opined, “Maybe when we’re squirrels, we’ll be up in that tree”). Senior spoke to Salon about chores, overscheduling, and the only thing she and “Tiger Mom” Amy Chua agree on.

I don’t have children, but I might someday, and I found your book’s depiction of parenthood a little scary. Should I be scared?

That’s the first response like that I’ve gotten. I mean, from time to time I hear that people find the article that it was based on scary, but usually the “joy” chapters were enough to make people feel very deeply what both sides are. Should you be scared? No, that’s silly. Nor is it my intention to scare anybody. I think when parents look at it they’re just kind of like, yup. My intention was to write something about the way we live now. If the way we live now is scary, then that’s sad, I guess. But now I want to know what parts you found scary.

Well, I was a little scared by your interviews with parents who felt their lives were totally overscheduled, who were constantly stressed out by driving their kids to different activities. But there’s been lots of coverage of this problem among middle- and upper-middle-class parents, and I wonder if you’ve seen it changing at all. Have parents been pushing back against this kind of overscheduling?

Here’s the part where I tell you, I don’t read about parenting, so I don’t know. My chapter about that was about the origins of that, where it came from. What I was trying to do was sort of explain that this mania can be chalked up to [the fact] that we now have no identifiable role or script. So when a kid ceases to be like a laborer in the household economy, and is an emotionally priceless person, our sole job becomes to make the child happy and prepare the child for a future that increasingly looks very bleak economically, and that’s changing too rapidly for us to have a bead on. The pace of technological change is so great that we feel we’re just going to do anything we can for our kids because we can’t imagine what the future looks like.

My own instinct about this is that of course it’s not good for parents or children. And just to give a concrete example, our attempts to fathom the future tend to be wrong. In the ’80s, when I was growing up, I was told that it was really important to learn Japanese. That I wouldn’t be able to cope without learning Japanese. And similarly now, people are like, well, we’ve got to teach our kids Mandarin. You don’t want to sit here and say that’s wrong — maybe it’ll be right. But often our attempts at these things are hilariously wrongheaded.

After reading my book, I think one can reasonably conclude that a kinder thing for both of you would be to ease up, because it’s not rational to overschedule kids. It seems rational but it’s not rational. Just the way any sci-fi movie seems rational, but is very much the product of your present imagination and neurosis and preoccupations. But is that the part that made you anxious, about my book, the overscheduling stuff?

That made me anxious, and the studies about people getting less happy once they have kids, and about the toll kids take on relationships. But I’m curious what other people’s reactions have been.

People ask a lot about the joy stuff. Parents fixate on the joy stuff. One of the things that the happiness studies did not seem to do is, you measure your well-being, on a scale of one to five, and sometimes you have feelings that are really off the charts, but they’re still registered as a 5. So if you have one of these crazy magical mysterious moments with your kid — and I’m not religious at all, but the closest thing to moments of awe that I’ve had in my life have been with my child. And in studies nobody’s going out and measuring awe in people. They’re not measuring transcendent experiences, they’re measuring positive experiences. So if you have a really good night with your spouse, and a transcendent experience with your kid, you give them both a 5. But they’re obviously very different. So people have been really appreciative of that.

What was the biggest surprise for you as you reported this book?

I found a lot of the stuff about adolescents surprising; even though I had adolescent stepkids when I started my relationship with my husband, I still think I didn’t recognize the profound effect they had on folks and the way they were reconsidering their identities. Also, there is a stray tidbit that I found surprising, that adolescent girls express the wish to hurt their mothers more than adolescent boys do. I never thought that girls were these adorable pink passive puffy creatures or anything, but I really was struck by that. I don’t know if that study had been replicated — it may have been a one-off — but it was nevertheless surprising to see, because it wasn’t ambiguous. It wasn’t a tie.

And I was surprised that those compliance studies [about kids obeying or failing to obey their parents] existed, as a category. It was interesting that they thought to sit in a room for a while and see how often the mother was barking off orders at the kids. I also thought it was interesting that almost none of those had any dads in them. And I thought it was interesting that nobody thought to compare response rates, because there were such implicit sexist assumptions in those days, about who had greater authoritative power in the home, that I was very surprised that no one had bothered doing this.

When did those kinds of studies start looking at dads?

I think in the ‘80s, when women started going to work, they were suddenly looking at the effect of kids on both [moms and dads] with more aggression, but they were looking at everything with more aggression. There was generally a lot more social science in the ’80s anyway — the fields were growing. But you know, it’s funny, [psychologist Daniel] Kahneman’s iconic study was on women. That was in 2004, the study that looked at the 909 Texas women and what they were enjoying, and found that children ranked lower than laundry. A lot of these things still do focus on women.

One thing I found really interesting about the book was how you interrogated the goal of raising a happy child. You make a pretty convincing case that this might not be a very good goal — that parents might not actually be able to ensure their children are happy. What’s a better goal?

What I think is a more achievable goal is invoking a little bit of, you know, a productive kid. I mean, kids did used to work, and you do not want to go back to the Dickensian days with sweatshops with children in them, but you do want your kids to take a more active role in what the house is, because you want the kids to be more familiar with what the household economy is. I’ve been giving this a ton of thought. I think kids have almost no responsibility, and I find that unnatural. It makes the family this very strange place where you’ve got this awkward hierarchy where you’re working for and servicing this kid, but the kid is not the right person to sit at the top of that hierarchy. So it should be rebalanced in some way. And if what we’re going for is a sense of confidence and self-mastery in children, I think it’s much better for happiness and self-confidence to be a byproduct of something — that’s the only real thing that you can count on. It might be a slim area of overlap of agreement that I have with Amy Chua. At the very least she says that confidence has to come from self-mastery, and that’s not in principle a dumb idea.

I think moral instruction is underrated. I think it’s better for you to try and make your kid good. I don’t care how you do it. Whether you send your kid to Sunday school or sit there are tell them a hundred times what’s right and what’s wrong, I think that’s a much more realistic goal than trying to make them happy. They can know the pleasure of having done nice things for people. I do have strong feelings about productivity and morality and the value of hard work. It sort of tracks with what Freud said, that teaching somebody how to love and teaching somebody how to work, in principle — he said those are our two life goals, to know how to love and to know how to work. I think that in some ways those are spot on. And I think a kid feels such pain, knowing that a parent is trying really hard to make them happy.

You chose to focus on middle-class parents rather than on those living in poverty or those who are very wealthy. Can you talk a little bit about that decision?

I read some of the books about poor mothers — there’s a really good one called “Promises I Can Keep” by a pair of sociologists called Kathryn Edin and Maria J. Kefalas. I’ve read “Random Family,” and Annette Lareau’s “Unequal Childhoods” has a lot of great stuff also about poor families and working-class families. And what you learn really quickly when you read about poor families is that there is no way to write about parenting without also writing about the problems of poverty. And there is one point in “Unequal Childhoods” that seemed like such a good metaphor for the entire problem. She was talking about this one extremely poor family, and [the mother] needed quarters to do the laundry. And she didn’t have a bank account because it costs money to have a bank account, she never had enough quarters, and she exhausted the patience of every small business on her block, asking for quarters. She’d show up every week with $10 and go to the bodega and they would be sick of her and tell her no. I mean, is that a story about parenting or about poverty? I mean, you’re trying to do your damn laundry. That deserves its own book, that deserves thousands of books. So I didn’t think I could speak to that, it just wasn’t fair.

And the upper-middle-class mom problem has been done to death; there have been tons of books out there. And I was much more interested in aiming for the genuine middle. I mean there are some upper-middle-class people, but there aren’t a whole lot of people with nannies there, for instance.

What policies do you think would help parents?

You mean if it was me and I were king? And if there was no such thing as Congress? I would create subsidized childcare — and really rigorous, monitored childcare. There would be paid maternity leave, not the Family Medical Leave Act, which in all its benevolence allows for 12 weeks of unpaid leave if you work for a company of 50 people or more. I would make six paid months minimum, guaranteed sending parents back to where they came. I mean, in some countries you can actually keep your place at work, and it’s illegal to demote you when you return. People don’t lose traction and there’s no penalty. And parents are actually happier than non-parents in countries where there are generous benefits.

On a local level it’s nice to get someone like DeBlasio trying to get pre-K going. I think that’s a more modest goal and God bless him, I hope it works. Ironically I think Oklahoma has some sort of subsidized pre-K? I’m pretty sure it does, and it came about by a political fluke. I don’t think I have very imaginative solutions to this; my wish list looks like every other civilized country.

Did working on the book change your approach to parenting at all?

It did. If you read a lot about the parents of adolescent children, and what really makes them ache, you start to appreciate a lot of what having a 6-year-old is like. I mean, I have a 6-year-old, and he comes bounding home to me at night. And a lot of that physical contact is something I luxuriate in, because there will come a time when my kid will flinch if I try to touch him. And if you interview parent after parent about that, you can feel the kind of melancholy welling up in you, like, I really better self-consciously enjoy this.

I read a lot of social science, and that was great, and very helpful. I try and give my kid stuff to do around the house, I try and give him chores. I’m very aggressive about assigning that stuff now. And I try to tell my husband ahead of time if I need three hours on a weekend. This was very interesting, the idea that if husbands and wives hash out ahead of time in detail what the division of labour should look like before the kid is born, it would be helpful. And my husband and I didn’t do that; we just had this vague idea that we would both try as hard as we could. But now we do it, and it’s better to hash it out ahead of time no matter when you do that.

But I learned stuff from families too: The differences between the parents who dropped down while talking to their kids so that they were eyeball to eyeball with their kids, versus parents who didn’t, was sort of interesting, because you forget that it’s scary to be small. They were getting better results because their kid felt better understood. The cool thing about doing a book like this is that you get to hang out with all these parents and see how they handle periods of stress, and so it was interesting to see what they did in those moments when things get tough.

And I try to focus on the joy stuff more. That sounds cheesy, it sounds dopey, but when my kid says something magnificent, I try to write it down because it’s a nice dopamine hit later. And so much of the pleasure of parenthood is the memory of it, so it’s nice to be a documentarian.