Rick Perlstein’s three-part history of modern American politics has been one long cautionary tale about liberals writing off the right. “Before the Storm,” his extraordinary account of the rise of Barry Goldwater, opened with New York Times columnist James Reston writing Goldwater’s political obituary, after the GOP’s 1964 humiliation by Lyndon Johnson. “He has wrecked his party for a long time to come and is not even likely to control the wreckage.” Four years later, of course, Republicans took back the White House, and thanks to the fire on the right Goldwater ignited, they held it for 20 of the next 24 years.

“The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan” ends much the way “Before the Storm” began: with the Times writing the last chapter of Ronald Reagan’s career – in 1976, after he lost the GOP nomination to Gerald Ford. “At sixty-five years of age,” Reagan was “too old to consider seriously another run at the Presidency,” the paper editorialized. We know how that story really ended.

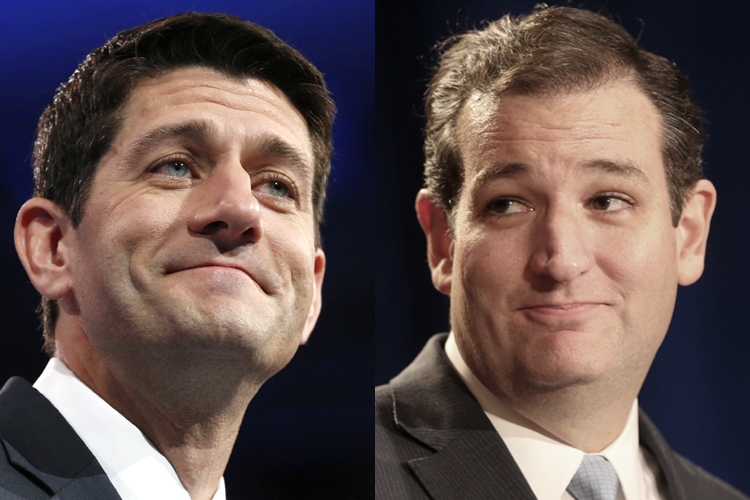

I always think of Perlstein when I’m tempted to predict the coming end of the GOP, when I’m sure demography will doom it, or when I believe its Tea Party fringe has done something so awful and destructive that this time, the American people will finally rise up, and send the haters and the know-nothings and the fear-mongers packing. Like, let’s say, Sen. Ted Cruz cynically blowing up the possibility of a House GOP border-crisis bill. That’s gotta wake people up, right?

But liberals like me have waited for that great rising up day many times in history, and just as it seems ready to arrive, the right rises up again, instead. People like me thought Goldwater, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were too extreme and divisive to lead their parties, let alone the nation, and Perlstein lives to show us in cringe-making detail how wrong we were. Read “The Invisible Bridge,” and you won’t be able to write off the idea of President Ted Cruz entirely. (I do nonetheless, but not blithely.)

Perlstein’s new book picks up where “Nixonland” left off. Having fractured the New Deal coalition and won over white working-class voters on issues of race, culture and the Vietnam War, to achieve a landslide over George McGovern, the president is inaugurated a second time – and just four days later, he announces an end to the war. He calls it “peace with honor,” but deep down, Americans knew we’d lost. Then things really fall apart.

Then the Watergate crisis escalates, an unthinkable Arab oil embargo escalates an energy crisis, and even meat prices skyrocket, leading to the shame of a once-great nation forced to eat organ meats. “Liver, kidney, brains and heart can be made into gourmet meals with seasoning, imagination and more cooking time,” Nixon’s consumer adviser told anxious housewives. A horrified nation learns that the president talks like a mafia don and will seemingly do and say anything to keep his job.

When he resigns, Americans have a choice: face up to the nation’s shortcomings that have been revealed so cruelly, and embrace “a new definition of patriotism, one built upon questioning authority and unsettling ossified norms,” in Perlstein’s words – or run away. They ran away, led by Ronald Reagan.

* * *

“Invisible Bridge” captures the genius of Reagan and his impeccable timing, coming after Nixon: He refuted the cynicism that Watergate inspired about America, while capitalizing on the cynicism it fostered about government. Perlstein makes a lot of the country’s fascination with the horror movie “The Exorcist” in the winter of 1974, as Watergate revelations unfurled. In it, Ellen Burstyn’s secular Georgetown career lady finds that her 12-year-old daughter has been possessed by a masturbating demon who swears like Richard Nixon. Her name is Regan, one of those androgynous names suddenly in vogue in the gender-bending ‘70s (which also, weirdly, sounds a lot like the name of the 40th president). Burstyn turns to a priest for help: “I’m telling you that thing upstairs isn’t my daughter!” she cries, echoing lots of parents of daughters in that era.

Once exorcised, a calm young Regan wears a lovely coat of red, white and blue. “She doesn’t remember any of it,” her relieved mother tells a friend. Perlstein doesn’t go on to make the obvious point, but I will: Ronald Reagan was the country’s exorcist, driving out the demons of suspicion and self-doubt (while also taming unruly daughters), so the pure, innocent country could reemerge from the humiliations of Vietnam and Watergate and thrive again. We wouldn’t remember any of it. Or so many hoped.

While pundits and even some party elders, including Barry Goldwater, insisted Republicans must cut Nixon loose, Reagan supported him to the end. He shamelessly appropriated civil rights language along the way: Nixon’s congressional inquisitors were “night riders” out for a “lynching.” When a spending cap ballot measure he backed fails in California, Reagan compares himself to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. What if King had given up on his dreams after a few disappointments? Well, Reagan won’t give up either.

Over and over, the media underestimates him. As Reagan leaves the governor’s office in Sacramento in 1974 (the office reporters hadn’t expected him to win eight years earlier), Joseph Kraft declares “the end of backlash politics.” The rise of liberal Jerry Brown meant “Reaganism has had it,” Kraft wrote. Politicians on both sides were giving up the angry politics of George Wallace and, yes, Reagan.

It was a tough time to be a Republican generally. Reince Priebus thinks he’s got a hard job: In the wake of Watergate, only 18 percent of the country identified as Republican, and the party resorted to buying airtime for a television special gamely titled “Republicans are people, too.” As they did after the Goldwater defeat, pundits and establishment Republicans insisted that moderation and tolerance were the key to a GOP revival, but Reagan disagreed, and he was proven right.

Perlstein shows how the divorced Hollywood playboy became the unlikely tribune of family values. The man who set back the women’s movement might have been motivated by payback: He had suffered as “Jane Wyman’s husband,” playing a supporting role to her rising star. Left by Wyman, he beds everyone he can, then he takes up with Nancy Davis, and adopts her father’s far-right politics. Their daughter Patti was conceived before they were married.

Yet this was the man who was able to unite evangelical Protestants and blue-collar Catholics who were in revolt against the pro-choice, pro-ERA, pro-busing, anti-family elites. A new outfit called the Heritage Foundation hired some folks to work with parents rebelling against the inclusion of “liberal” books in West Virginia’s curriculum. Their job was “finding little clusters of Evangelical, fundamentalist Mom’s groups” and helping them grow. Conservatives would have called them “outside agitators” if they’d been on the other side.

Up in Boston, some Irish Catholic “Moms” became the public face of the backlash against busing, and the two groups of moms begin to make common cause: The women of South Boston’s ROAR, Restore Our Alienated Rights, turn up to protest a pro-ERA hearing at Faneuil Hall and take it over. The building of this unlikely New Right coalition mostly goes unnoticed by media and the Republican establishment. As primary season began in 1976, President Ford’s forces were blindsided by the “unexpected Reagan success in certain caucus states,” one internal memo reported. Reagan was turning out voters who were “unknown and have not been involved in the Republican political system before” and seemed “alienated from both parties.”

* * *

If Reagan is the man who sold us the “invisible bridge” of the title, Ford represented the visible bridge to our post-Watergate, post-Vietnam future — and he all but collapsed. After Nixon resigns, Ford enjoys a brief honeymoon; the media tell us that he made his own English muffins. He’s a kindly ’50s sitcom dad with a pipe, but he has a wife perfect for the ’70s – Betty Ford could have been a friend of Maude or Mary Tyler Moore. It might have worked: A bridge needs a landing on both sides of the divide.

But Nixon left Ford holding the bag – the truth about lies and loss in Vietnam, the criminality of Watergate and the CIA/FBI scandals that preceded it, the quick fall of Saigon; an energy crisis, an inflation crisis, and a backlash against feminism and liberalism as embodied by his own wife, the abortion- and ERA-supporting Betty, who was popular with the country, but not so much with the right. The highlights of Perlstein’s chapters on the 1976 Republican convention in Kansas City are the accounts of how Ford and Reagan competed via the pageantry of dueling convention entrances by Betty and Nancy.

The book’s one shortcoming is the excessive attention it paid to that convention showdown; I learned entirely too much about amendment 16c, and other delegate-rule arcana. The reason to soldier through Perlstein’s convention-tick tock is to see Ford’s forces utterly sell out Republican feminists, accepting antiabortion and anti-ERA platform planks without a fight, while trying to block an attack on Ford’s foreign policy. In the end, Ford would throw women under the bus, but not Henry Kissinger. So today, when you hear establishment Republicans bemoan the misogynist crazies who threaten their hopes of winning back the White House and the Senate, remember how that same establishment appeased those crazies on women’s issues starting with the 1976 convention, and try to withhold your sympathy.

Ford’s biggest sin to the right, Perlstein writes, was having to preside over a world where “the rules must apply to America as well.” When Saigon becomes Ho Chi Minh City and the Khmer Rouge take over Cambodia, Ford is easily portrayed as the dupe who’s advancing Nixon’s policy of détente with the Soviet Union – of course it would turn out to be a French word — which came to be translated as “surrender” on the right. After a fairly polite beginning to what became an ugly primary challenge, Reagan goes after Ford hard over the Panama Canal treaty in a Memorial Day 1976 campaign speech. “Have we stopped to think that young Americans have seldom if ever in their lives seen America act as a great nation?” he asked. That’s trademark Reagan, and here Perlstein interjects the obvious: Clearly, the civil rights movement hadn’t counted.

The release of “Invisible Bridge” is timed to the 40th anniversary of Nixon’s Aug. 9 resignation, but it comes out the week of two other important anniversaries. Aug. 6 marks 49 years since LBJ signed the Voting Rights Act, which he admitted to Bill Moyers would hand the South to the GOP indefinitely. Five days later, the Watts riots broke out in Los Angeles, and the country began to say “Enough” to civil rights liberalism. This is the history Perlstein chronicled so well in “Nixonland,” and he picks it up again, a little less surely, in “Bridge.” Race runs through the backlash to modern liberalism first channeled by Goldwater, then Nixon and then Reagan – and it runs back to the Civil War.

Throughout the book he refers darkly to the “suspicious circles” of liberal elites and journalists who believed the lost war in Vietnam, the shame of Watergate and the revelations of CIA and FBI wrongdoing revealed something important and deeply troubling about the state of our union. Perlstein takes the term “suspicious circles” from a Reconstruction-era New York Times editorial deriding people like abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison who were warning that the post-Civil War South was slipping back into racist tyranny. “Does he really imagine,” the Times wrote of Garrison, “that outside of small and suspicious circles, any real interest attaches to the old forms of the Southern question?”

Of course the “suspicious circles” were right about the post-Reconstruction South, and they were right about Nixon, Watergate and Reagan, too. But harking quietly back to the period after the Civil War helps Perlstein remind us that the backlash to the civil rights movement was connected to that earlier backlash. This country does great things, albeit a little late, like fighting a war to end slavery, and then going back 100 years later to abolish Jim Crow. And then it’s finished for a while. After the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, there would be no second Reconstruction, there would be only recrimination.

Perlstein also wants us to remember: Backlash is usually abetted by journalists, who too easily succumb to outrage fatigue. The post-Watergate conservative uprising marked the beginning of the “both sides do it” narrative that degrades political reporting to this day. Nixon was a victim of a media establishment that conservatives denounced as “liberal” – and then we learned media darling Jack Kennedy was responsible for some of the worst domestic and foreign plotting, spying, espionage and coverups in history, only nobody cared. From behind enemy lines at the New York Times, Nixon speechwriter turned columnist William Safire railed at his colleagues for acting as though his old boss had invented presidential wrongdoing, when their beloved Kennedy had plotted to assassinate Fidel Castro while cavorting with the former mistress of Mafioso Sam Giancana, Judith Exner.

Working the refs worked for the right. Suddenly, the media didn’t have much appetite for revealing wrongdoing, on either side. Frank Church thought he could ride his CIA investigation into the White House, but he found himself the victim of outrage fatigue. “To see a conspiracy and coverup in everything is as myopic as to believe that no conspiracies or coverups exist,” the Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham told a publishing trade group in 1975. Now when the CIA complained about a story, the great William Greider lamented, the once “adversarial” media “rolled over on its back to have its belly rubbed.”

* * *

Of course everything Perlstein covers in “Invisible Bridge” feels eerily current and familiar. The parallels to the backlash to President Obama are obvious.

The revolt against the Equal Rights Amendment and Roe v. Wade that began in the mid-1970s continue, in the renewed attacks on abortion rights and even contraception today. The conservative backlash against Common Core has its roots in the right-wing uprising against ’70s curriculum standards abetted by those early Heritage Foundation staffers. When Joni Ernst talks about “nullification” of laws passed under our first black president, she represents the enduring Goldwater alliance between anti-Washington Northerners and states’ rights Southerners that powered the presidencies of Nixon, Reagan and both Bushes, too.

When Sen. John McCain calls President Obama “cowardly” for not castrating Vladimir Putin over meddling in Ukraine, or neocons bray that the president has “abandoned” Iraq, we are living with the results of refusing to face up to the limits of American power, even as the lone remaining “superpower.” They’ve been screaming about this since Jerry Ford had to go out and attack Cambodia to “rescue” the SS Mayaguez – unnecessarily killing 49 American servicemen because Henry Kissinger believed “the United States must carry out some act somewhere in the world which shows its determination to continue to be a world power.”

Again the media are complicit, covering the Tea Party as though it was something new and novel and tailored to the times, rather than the Goldwater-Nixon-Reagan coalition dressed up in funny costumes, many of them still animated by an abiding racism. In fact, the American right has lost some of the authentic anti-Wall Street, anti-crony capitalism energy that powered Goldwater’s rise. But Perlstein shows how Democrats have been complicit too, from Jimmy Carter to Barack Obama.

Carter was the Democrats’ Reagan, in a way, smiling and reassuring like Reagan was, but shorn of ideology. The Georgia governor made us feel better about America’s racist past, like maybe we had overcome – as long as we didn’t look too closely at his earlier efforts to court George Wallace and his supporters, or hold it against him when he defended white neighborhoods seeking to preserve their “ethnic purity.”

In fact, many of the Democratic Watergate babies swept into power in ’74 and ’76 were like Carter, as much a rejection of George McGovern as of Richard Nixon. Gary Hart famously declared “the end of the New Deal,” insisting “we’re not a bunch of Hubert Humphreys.” He and much of his cohort had no strong ties to the party’s historic labor base. Nor did they offer much of an economic alternative to pro-business Reaganomics and the fetishizing of the free market.

Likewise, Barack Obama told supporters he aspired to the “transformative” presidency of the “optimistic” Ronald Reagan, not the crabbed, partisan battling of Bill Clinton, the Democrats’ only two-term president since Harry Truman (although, to be fair, Clinton delivered his party’s final rebuke to McGovern, even though he cut his teeth working for the liberal Democrat’s 1972 campaign). Obama inherited the McGovern coalition of minorities, women and liberal whites when it had grown into a majority of the country, but he channeled a vague but powerful longing for “hope” and “change,” while hoping to avoid the ideological conflict genuine change would require.

The remnants of the Nixon-Reagan coalition made that impossible. But as a centrist corporate Democrat who is also conflict-averse, Obama took too long to articulate why the nation must break from the anti-government, pro-free market approach Reagan pioneered. He found his inner FDR in time to beat Mitt Romney in 2012, but the damage to his two mandates, and his presidency, had been done, by Tea Party reaction and, yes, racism. And by the Democrats’ recurrent belief that their inner righteousness will redeem them.

In all three of his books Perlstein rubs liberals’ noses in the difference between the way we face adversity, and the way the right does. We trust in our own moral superiority – and lately, in our moral superiority tied to demographic destiny, which seems unbeatable. But they just get busy trying to out-organize the other side – whether the other side is Ford Republicans or Obama Democrats – and after a few setbacks, they beat us anyway. Over and over since the rise of Barry Goldwater, Democrats and much of the media have concluded that the Republican Party is dead if it won’t court new voters, and over and over they don’t do that – and they win.

This time, Democrats seem to have a little more genuine electoral ballast on their side, given the rising power of Latino voters and younger, single women, two groups Republicans can’t and won’t court if they want to hold onto their fearful older, white Christian base. So maybe this time the Perlstein formula won’t work. Maybe he, or some historian who comes after, won’t be able to rely on quoting self-congratulatory Democrats along with smug pundits writing off Mitt Romney as they miss the rise of President Cruz.

Democrats ought to hope that’s true – while they work at least as hard as Republicans do, to make sure of it.