With President Obama on the cusp of implementing some (as-yet-unspecified) executive actions to curb deportations and grant work permits for undocumented immigrants, we’re barreling toward what looks to be another knock-down, drag-out fight over immigration. And whenever immigration moves to the forefront of national politics, the very worst nativist instincts of the conservative movement reassert themselves and add a bit of old-timey, anti-immigrant flavor to the debate.

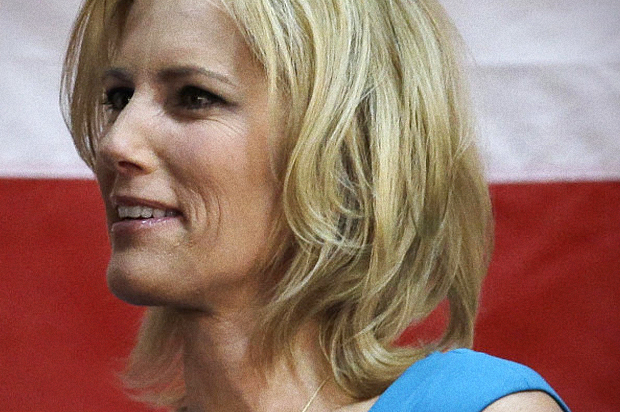

Radio host Laura Ingraham is one of the more influential anti-immigrant voices on the right, owing in large part to her sweet gig as a contributor for ABC News. She was a key figure in Eric Cantor’s stunning primary defeat this summer, lending her voice and influence to Cantor’s challenger as they painted the former House majority leader as a pro-“amnesty” squish. Her positions on immigration are so repellent that she makes Bill O’Reilly, the thought-leader for scared old white conservatives, seem reasonable by comparison. She’s a real feather in your cap, ABC!

Anyway, with immigration back in the news Ingraham was back on the radio offering her unique solutions for how to deal with the issue. One of her key policy recommendations is to amend the Constitution to prohibit birthright citizenship, “which is opening the door to all sorts of fraud and gaming the system,” she explains. You might remember from a few years back the hullabaloo over “anchor babies” – pregnant women who were supposedly entering the country illegally just so they could give birth and then somehow cash in on their offspring’s citizenship status. The phenomenon was driven almost exclusively by conservative hysteria, and birthright citizenship was at the center of it.

Birthright citizenship is a fairly straightforward principle: If you are born within the territorial boundaries of the United States and your parents are not in the service of a foreign government (i.e., diplomats, soldiers, etc.), then you are citizen of the United States. Your parents don’t have to be citizens, nor do they have to be legal residents. That’s been U.S. policy ever since the 14th Amendment was ratified, and it’s enjoyed Supreme Court affirmation stretching all the way back to 1898. Birthright citizenship is one of the great democratizing principles of American law: If you’re born here, you’re afforded the same rights and privileges as anyone else, regardless of who your parents are.

The nativists of the conservative movement, however, don’t think this should be the case. Not only that, they believe that birthright citizenship was never intended to be U.S. policy, and that the courts and the government have been misinterpreting the 14th Amendment these past 150 years. As you might have guessed, this is a radical idea that has little to no precedent or legal theory to back it up.

Their argument boils down to one phrase in the amendment: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” Supreme Court justices, lower court judges, legal scholars and the drafters of the amendment all agreed that the phrase was meant to exclude only those people whose parents were actively serving a foreign government. People like Ingraham, however, insist that “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” means your parents can’t be citizens of a foreign nation. It’s the sort of tendentious, bad-faith legal reasoning that would make the Halbig folks proud.

All the dispositive legal history wasn’t enough to dissuade the anti-immigrant movement, and the notion that the 14th Amendment is being wrongly applied to the children of undocumented immigrants became an article of faith and an activist cause. In 2011, a group called the Immigration Reform Law Institute unveiled state-level model legislation that redefined citizenship to conform to the nativists’ boutique interpretation of “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The group’s stated intent was to provoke a lawsuit and trust that the conservatives on the Supreme Court would throw out over a century of precedent and rule in their favor.

The push to end birthright citizenship also reached some of the highest levels of the Republican Party. In 2010, Lindsey Graham called for birthright citizenship to be reexamined: “We ought to have a logical discussion. Is this the way to award American citizenship, sell it to somebody who’s rich, reward somebody who breaks the law?” Mitch McConnell and John Boehner, who will lead both houses of Congress come January, thought the idea was at least worth considering. “There is a problem,” Boehner said at the time. “To provide an incentive for illegal immigrants to come here so that their children can be U.S. citizens does, in fact, draw more people to our country.” One of the first things likely 2016 Republican presidential candidate Rand Paul did when he made it to the Senate in 2011 was to introduce a resolution ending birthright citizenship.

As Republicans became more sensitive to the fact that they needed to improve their standing with Hispanic voters, calls for ending birthright citizenship were replaced with calls to pass comprehensive immigration reform. But the cause still has adherents in the GOP – Iowa Rep. Steve King, unofficial leader of the House anti-immigrant caucus, introduced legislation at the beginning of this session of Congress to redefine citizenship.

But the fact that this grossly nativist and legally dubious argument remains so popular among hard-line conservatives helps to explain why meaningful immigration reform legislation remains so elusive. To address the problem of undocumented immigration, the base of the Republican Party and its loudest megaphone – talk radio – want to change the Constitution, dismantle a century and a half of citizenship policy, and alter one of the fundamental notions of American identity. This, in their minds, is a practical thing to do. When pundits and centrist concern trolls ask why President Obama and the Democrats just can’t reach an immigration compromise with the Republicans, this is part of the answer. The people who vote the Republicans into power (or, in Cantor’s case, out of power) have some radical ideas when it comes to immigration reform.