A while back, I was having some beers with the founder of a small atheist publishing house. I’d recently savaged one of his writers in print, and I started laying out a pretty standard critique of the New Atheists — that they caricature religion, they’re elitist, they’re too aggressive and so forth.

The publisher listened for a while, and then told me, politely, that I was being young, harsh and stupid. Until not very long ago, this kind of vocal, proud atheism just didn’t have a solid place in the public eye. These writers had carved out some space for freethinkers to thrive. And that alone was an achievement.

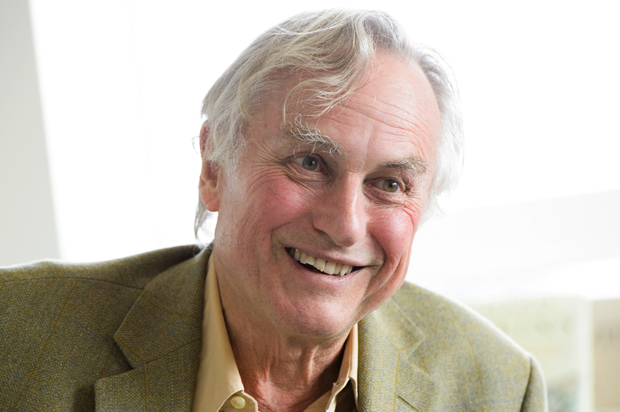

So, say what you will about Richard Dawkins, but give him credit for this: the man’s a pathbreaking iconoclast. In 1976, as a young evolutionary biologist at Oxford, Dawkins wrote “The Selfish Gene,” one of those rare books that’s accessible to lay readers, even as it shapes an academic field. The book established Dawkins’ reputation as one of the more elegant public explainers of Darwin’s theory. Then, in 2006, Dawkins’ “The God Delusion” hit bestseller lists, and made his name synonymous with a certain kind of hardline atheism.

“Brief Candle in the Dark,” released last week, is the second installment of Dawkins’ autobiography (the first, “An Appetite for Wonder,” came out in 2013). A loose collection of reminiscences, the book ranges from Oxford lecture halls to far-flung research stations. The picture that emerges is of an agile thinker who delights more in collaboration than confrontation.

Reached by phone during a visit to New York, Dawkins spoke with Salon about Twitter, pluralism, his love of computer programming and why he thinks Ahmed Mohamed is a fraud.

You’re looking back at your career. Do you think you’ve been a success?

I’ve written a dozen books or so, and they’ve all sold very well. They’re all still in print. I get a lot of fan mail. I guess from that point of view, objectively measured, yes.

Do you feel like you’ve influenced people?

I think those who read my books seem to be mostly convinced.

When it comes to convincing people about big science issues, like evolution or climate change, there’s a split between those who favor a diplomatic approach, and those who are more open to confrontation. Do you worry that you’ve alienated as many people you’ve convinced?

I think both methods are worth pursuing. It’s good that some people pursue the more conciliatory approach. Some people, perhaps Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and me, have pursued the combative approach, which I think works for some people. I may have alienated some people, but I’m hoping that I won over more.

As part of my reporting work, I’ve interviewed evangelical Christian scientists who think that evolution is real, and who do science outreach within evangelical communities. More than one has said something along the lines of “Richard Dawkins makes my life a lot harder.”

Yes, they do say that. I’m a bit skeptical. If the audience thinks they have to abandon their religion in order to accept evolution, it is possible that I alienate them and make the job harder for those scientists whose only concern is to convince people of the truth of evolution.

For me, you haven’t won if you’ve done that. I’m concerned about the whole rationalist exercise. If what you aim at is not just science education, but a complete rational explanation of the world, then I think that I can defend what I do, because my agenda is a broader agenda.

Do you think it’s worth pursuing those halfway agendas, though?

I do think it’s worth it. I applaud and laud the National Center for Science Education for doing that, but I have a somewhat different agenda.

What would victory look like for you?

It would be a complete abolition of supernaturalism and superstition of all kinds. So, it would be the abandonment of things like homeopathy in the medical field. The abandonment of religion as well.

To play the devil’s advocate here for a moment, is there some need for cognitive pluralism — a mix of approaches to reality? Is there something anti-pluralist about your approach?

I think it’s a need for a mixture of approaches from a purely political and practical point of view.

Wait, I don’t mean a mix in terms of science communication styles. I mean that, if we arrive at a world where everyone’s part of this rationalist project, is that a world where pluralism still exists?

Well, pluralism is a funny word to use, in a way. There’s great plurality in the rationalistic approach. We’re pluralists in the sense that we still appreciate art and music and poetry and love. Science itself is immensely pluralist.

In what way?

There are many different sciences. No one person can grasp it all, but we are advancing on a broad front with science. We are, every year, every decade, every week, advancing our scientific knowledge of the universe and of life.

I don’t think pluralism of topics and pluralism of worldviews is the same thing.

No, they’re not. I don’t think I want to embrace a pluralism of worldviews. I think that naturalism is a big enough worldview to cover everything.

In your book, you’re celebrating collaborations and interactions with other scientists and thinkers. At the same time, you have this public reputation for combativeness. Do you feel misunderstood?

Yes, I think that if you read either of these biographies, ‘An Appetite for Wonder’ or ‘Brief Candle in the Dark’, what you find there is a rather mild-mannered, friendly, genial, humorous person, I would like to think. I don’t think I’d call myself combative. I think I’d call myself a lover of truth. I’m intolerant of bullshit. I’m intolerant of obscurantism. I hope I’m always polite about it. I hope I cut through obscurantism with clarity. I think it’s probably true, clarity can sound aggressive.

Why does that clarity make people uncomfortable?

I’m not sure. I think when you’re used to hearing a lot of waffle, when somebody suddenly cuts through that with clarity, that does sound threatening to some people.

In the book you describe “The God Delusion” as being satirical in a way that’s not often appreciated. How does satire relate to this clarity?

Satire is a valuable, and often humorous, weapon. It helps people see what they didn’t see before.

In your autobiographies, you come across as a curious guy. When you approach a scientific phenomenon that you don’t understand, you seem to say, “Let’s try to figure this out.” But when you approach a religious phenomenon you don’t understand, your reaction seems to be more along the lines of “Let’s satirize this.” Is there an inconsistency in your curiosity?

Well, I am curious, and, as you say, scientifically, I’m just plain curious and interested in getting the evidence. In terms of religion, I’m definitely curious as to why people are moved in the way they are to be religious.

I’m not sure what else I could be curious about. I’m curious about people’s motivation in being religious. I don’t sympathize with it because I looked at the arguments and found them wanting.

In your writing, and that of other New Atheists, there’s a lot of engagement with theology, and with arguments for God. There’s much less discussion about how anthropologists, sociologists and religious studies scholars understand the motivations for religion. It’s as if a whole branch of academic work just doesn’t factor in.

Well, I think that’s interesting, I just don’t happen to have written much about it. But other people have done that. I can’t write a book about everything.

I need to stress that the autobiography is really very little about religion, it’s much more these digressive, anecdotal, funny stories.

Do you go into interviews and wish people would ask you about science, and then you just get questions about religion?

[laughs] Yes, that’s very true, I do. Sometimes, it seems that the only book I’ve ever written is “The God Delusion.”

Why do you think evolution has become such a flashpoint in religion/science conversations? It seems like neuroscience, or physics, or many other areas could just as well be seen as challenging the Bible or religious orthodoxies.

That is a bit of a puzzle, and that’s something, perhaps, you need to ask the religious fundamentalists themselves. My guess would be two-fold. One is that [evolution] very clearly complicates the literal text of Genesis and other holy books.

The other is that there’s a kind of revulsion to the idea that humanity is related to apes, who have long been regarded as figures of fun. I think this was particularly the case in Victorian times when Darwin first came up with the idea. People were actually revolted, physically revolted, of the idea that they were cousins of chimpanzees.

It’s interesting that evolution tends to be described in these terms of ugliness or degradation. A lot of your work celebrates the aesthetics, the beauty, of evolution.

Very much so. I see science in general, and evolution in particular, as a deeply poetic and aesthetic experience. It is wonderful that we have a purely naturalistic explanation for the astonishing, astounding variety of life, the complexity of life, the beauty of life, the elegance of life and the powerful illusion of design that life carries. That is all wonderful and marvelous and poetic. The people who miss that are missing something very substantial.

How do you help people see evolution as beautiful?

I hope that most, if not all, of my books do that. I try to write in a style that verges on prose poetry, sometimes. I try to open people’s eyes to see how astonishing it is that we are here and we have brains big enough to understand why we are here.

You’ve written beautiful books diving into these large questions. But in the last few years, it seems like you’ve become best known for the things you say on Twitter. Are your friends trying to drag you off of there?

I think that is unfortunate. I would rather people concentrated on my books. Some of the things I’ve done on Twitter have been jokes. There’s not much you can do in a 140 characters. It isn’t a sort of art form.

In the book, you defend your tweet comparing the number of Nobel Prizes won by Muslims with the number won by affiliates of Trinity College, Cambridge.

I first wrote a tweet calling attention to the remarkable fact that the number of Nobel Prizes won by Muslim societies is, I believe, one — possibly two — compared with hundreds by Jews. And yet the number of Muslims in the world is in the billions. Well, that’s an interesting comparison.

But then I thought to myself, oh dear, I can’t compare Jews with Muslims because that will arouse all the hostility, because of Israel and Palestine. So I impulsively changed Jews to Trinity College, Cambridge. That was a mistake. I should have stuck with Jews because that’s the really important point that needs to get a conversation going.

We need to ask ourselves why these two cultural traditions, Judaism and Islam, have produced such a fantastic imbalance in the number of scientific achievement.

If you took most largely non-European groups of people, they would have very few Nobel Prizes. Even more so when you look at the dynamics of colonialism, such as the wrecking of Muslim societies and empires.

I implied that by saying, in the very same tweet, that in the Middle Ages Muslims are at the forefront of science, and I’ve said, “What has changed?” And you’ve just given the answer.

I guess that, in light of your recent set of tweets, which I know you backed off about, concerning Ahmed Mohamed —

I didn’t back off.

Oh, my apologies. But you qualified it a bit, right?

Well, this has nothing to do with “Brief Candle in the Dark” and I would like to stress that. But yes, I don’t mind talking about Ahmed Mohamed if you want to.

I think there is a connection. You defend this earlier tweet about Muslims in your book, and now you have another contentious tweet about Muslims, this time involving Ahmed Mohamed.

I’m not interested in the fact that he’s a Muslim. He’s a fourteen-year-old boy who pretended to have made a clock which he didn’t make; so he was a deceiver. On the other hand, he’s only fourteen. There are other fourteen-year-old boys who really do make things like clocks, who really are creative, and they don’t get invitations to the White House. He got an invitation to the White House by what is, without any doubt now, a hoax.

If you think about when any of us go into an airport, any security-conscious situation — airports are among them, schools are among them — you must not, you dare not make a joke about a bomb. You make a joke about a bomb, however much you laugh and however much obviously it’s a joke, you will get arrested. That’s the zero tolerance policy of the United States’ Homeland Security system.

Sure.

Ahmed made a joke. He took the guts out of a clock, put them in a box with wire dangling all over the place. I can’t begin to guess at his motive, but this was the kind of thing which will get you arrested in any airport security or any high-security situation.

What motive could he possibly have had for doing it? I don’t know, but I do know that he has garnered an enormous amount of support and adulation, scholarships.

Is there a dynamic of profiling or prejudice in his arrest?

Imagine if you went into an airport with a box that was electronics and wires and batteries and god-knows-what. You couldn’t have a hope of getting that through the airport security.

That’s probably true.

You don’t have to be profiled for that.

But he was in school, not at an airport.

But a school is a highly sensitive place. There’ve been so many acts of terrorism in American schools that schools are like airports, subject to the same kind of rather ugly security inspectors.

I’m at a loss to think of what his motive was, in taking the guts out of a clock and putting them into a box. I can see that he’s crowing with delight at all the attention he’s getting.

There’s a perception that New Atheist writers — including you — have a harder time seeing bigotry and prejudice when it’s directed against Muslims than when it’s directed against another group.

My opposition is to all religions, but if there is one religion which is more prone to violence and more prone to a stated ambition to take over the world, then I will naturally focus a certain amount of attention on that one religion.

OK.

But I am against all religion.

It seems that if you were approaching, say, an organism’s adaptation, you’d be looking for a lot of possible routes through which natural selection shaped that trait. I know it’s different, but looking at the evolution of cultures, it seems like you’re focusing pretty exclusively on religious belief as the driver of this particular phenomenon. But there are a lot of different routes through which violence can come about.

Human culture is not my subject. I’m not setting out to explain human culture. Evolutionary biology is my subject. If an aspect of human culture sets itself up in opposition to the science that I do, then I naturally tend to react to that.

I’m not sure that I quite get your point about different routes. What would you have me do?

There’s obviously a connection between violence and some Muslim cultures right now.

But does violence come from specific beliefs? From political battles? From environmental pressures? Something else? There are all these different sources of violence, which can then become entangled with religious belief. It seems like you’re focusing on one possible cause pretty insistently.

I recognize that the vast majority of Muslims in the world are peaceful, law-abiding, wouldn’t-hurt-a-fly. But nevertheless, the minority who are violent are very violent: beheadings, stoning, chopping people’s hands off, lashing them for the crime of apostasy. This is something which, on the whole, is not practiced by Christians or Jews or Hindus or Buddhists, and I don’t think it can be called bigotry to concentrate on those people who are lashing and stoning and beheading, and stopping women from driving and all the other horrific things that are going on.

Of course, most Muslims don’t do that. But the few people who do do that are mostly Muslim.

It’s the same question that comes up with adaptation and debates about adaptationism, right? It’s always about untangling correlation and causation, which seems really hard.

What’s the connection with adaptation?

In both cases, there’s a form of historical extrapolation from the present. To say that something specific about Muslim-ness drives violence is to make certain claims about history as well.

That may be, but I don’t see the connection with adaptation. I mean, it is a fact, isn’t it, that Christianity doesn’t appear to be — I mean, it does motivate people to bomb abortion clinics. But apart from that, if you make a list of death penalty for apostasy, no, Christianity doesn’t do that. Whipping people for adultery: no, Christianity doesn’t do that. Stoning people for adultery: no, Christianity doesn’t do that.

Chopping off people’s hands, chopping off people’s heads — these are simple matters of fact. These things are done by Muslims, and they appeal to their Islamic scriptures when they do it. The vast majority of Muslims do not do that, but the vast majority of the people who do do that are Muslims.

It just seems like the world is a small laboratory in which to test these comparisons.

It’s a small laboratory.

But I’m worried about this harping on about Islam. The book has nothing to do with Islam.

OK, I have a question more specifically about the book. If you hadn’t become a biologist, what would you have done? Do you have another fantasy career?

Yes, I think probably a computer programmer. It became quite a vice for me. I was an addict in the sort of way that I wouldn’t go to bed, I wouldn’t eat, I was so addicted to computer programming. I could imagine that would have been an alternative career.

The genome looks a lot like code, doesn’t it?

Very much so. That is a fascinating fact. I suspect that it had to be that way. I suspect that evolution by natural selection wouldn’t work unless genetics was digital, unless genetics was a kind of branch of computer science. I think it has to be that way to be sufficiently accurate, sufficiently high fidelity, to mediate evolution by natural selection.

What puzzle or what question is getting you most excited right now?

Well, I would love to understand the origin of life. I feel that we Darwinians understand pretty much how life evolved once an accurate genetic code has appeared. But that very first step, the production of the first self-replicating entity is still a mystery, and it’s one that a lot of very clever people are working on.

Another one I suppose is the mystery of subjective consciousness. I’m intrigued by that, and I think that’s a more difficult question. Subjective consciousness is a profoundly difficult question, one which should eventually yield to, probably, a combination of biology and computer science.

It is beautiful that we still have these gigantic questions, right?

Yes. And if I were a physicist, I would add, “Where do the laws of physics come from? Where do the fundamental constants come from?”

Do you think we’ll ever come to the end of the questions?

I love that — I love to think about that. I find equally exciting the thought that science will come to an end and will be fully understood, on the one hand. On the other hand, there will always be another hill to climb once you’ve gotten over this one.

I think scientists are divided by those who think that it will come to an end and will be solved, and those who think that it will never come to an end — that there will always be new distance with questions opened up. I think that both of those possibilities are entrancing.