The economy is robust. We are flush with conveniences and gadgets to make our lives easier, and entertainments and toys to make our lives fun. But we are bored and soft. And we're silly, too, in our giant SUVs, patrolling the suburbs as if we're crossing the Outback, not merely dropping the kids off at soccer practice. We wonder: If the bottom fell out and we were thrust into a catastrophic economic depression, could we make ourselves eat rats and caterpillars, like the castaways on "Survivor"? Would we know how to build a lean-to out of tree branches, or start a fire by rubbing two sticks together?

Of course, we could just ask the homeless for tips on finding the choicest sleeping spots under the freeway or the best dumpsters to rummage. Or we could go to the working poor for advice on feeding and housing a family on minimum wage. But that's not nearly as titillating as watching CBS's castaways eat rats for $1 million. Is it any surprise that "Survivor" pulls in its highest Nielsen ratings in households with incomes over $80,000 and its lowest in households with incomes under $30,000?

Middle-class Americans fear hardship, yet crave it, because it's been bred out of most of us -- which was why there was such a festive air to all that pre-Y2K stocking of the larder. And which is why "Survivor" is the perfect show for our times: It's all about facing contrived hardship. The castaways may have to forage for food, but there's a medical team standing by; the show also provides them with all the sunblock, Band-Aids, iodine, anti-diarrheal medicine, tampons, aspirin, condoms and contact-lens cleaning solution they need to rough it in relative comfort. Let's face it: "Survivor" is so popular with well-off viewers because it offers a vicarious respite from the privileges of modern life we're always complaining about. How long could we go without cell phones, hot showers, e-mail, microwave popcorn and TV? Would we just die without our DVD players and fruit smoothies?

A year ago, Britain's Channel 4 asked a similar question in "The 1900 House," a reality TV series that held British viewers in thrall the way "Survivor" is gripping American viewers now. Channel 4 held auditions to find a family who would be willing to live for three months as a middle-class family would have in 1900 London. The family would move into a turn-of-the-century Victorian house that had been stripped of all modern amenities -- goodbye electricity, indoor toilets, central heating -- and restored back to the days of gaslit lamps, outhouses and coal-burning stoves. The family would have to observe Victorian modes of dress and entertainment, and eat and use only those foods and products that would have been available to a middle-class family in Britain in 1900. A camera crew would be there every day to record the experiment, and there would also be a "video diary" camera set up in a closet where the family members could confess things they didn't want the others to hear.

A psychologist was invited to review the hundreds of audition tapes, in hopes of finding a family who would be able to put up with one another for three months without any of the modern distractions that make family life bearable. A pudgy dandy named Daru Rooke, who curates a museum about Victorian life, oversaw the restoration of the house with a kind of sadistic glee, making sure that every article of furniture and clothing, every bit of food and medicine, every household implement, was authentic. The resulting series, the four-part "1900 House," began its first American run on PBS last week; it's an intimate, eye-opening and completely fascinating look at how radically domestic life has changed over the past 100 years.

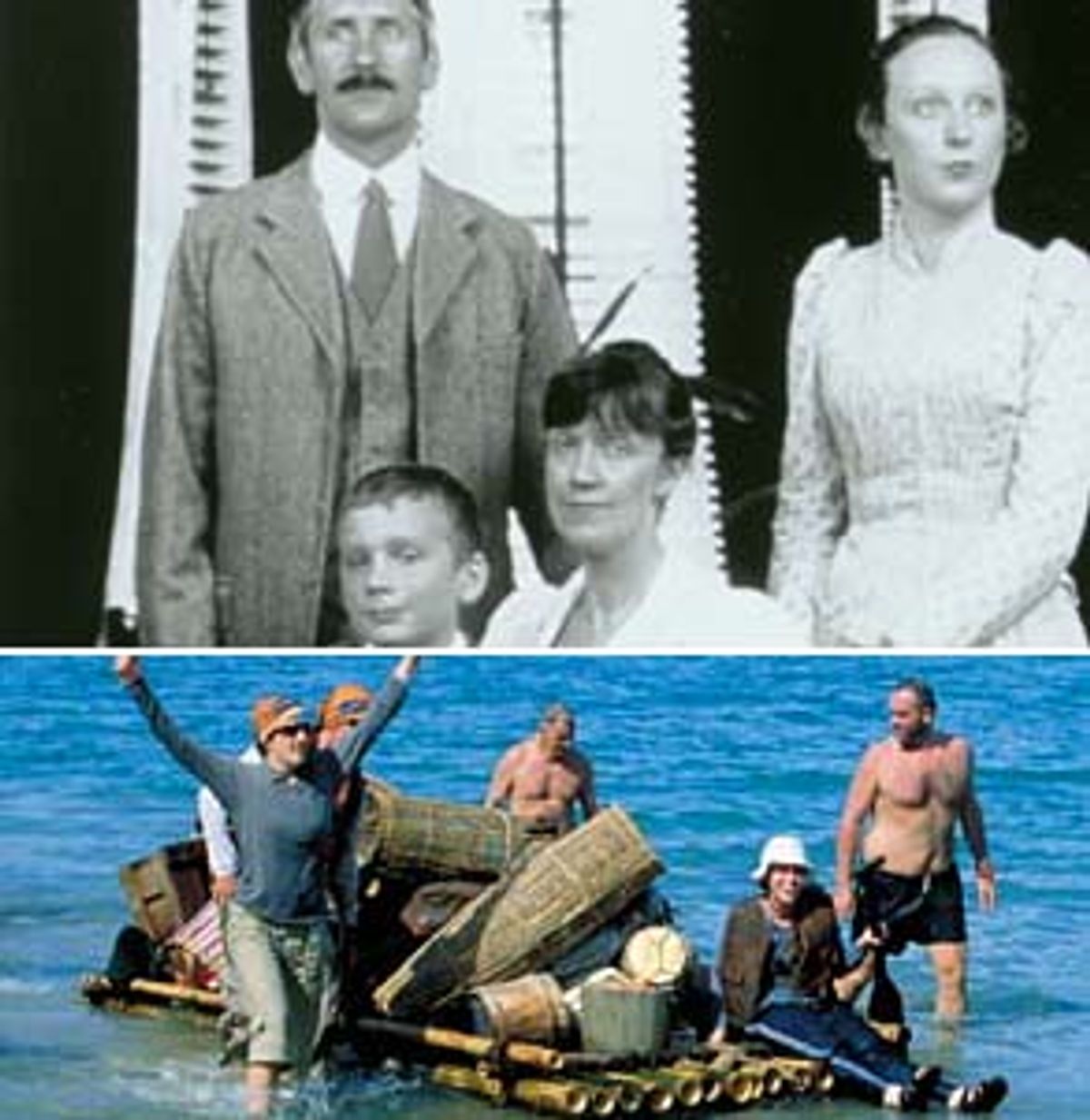

They weren't marooned on a desert island, but the plucky Bowler family -- Paul, Joyce, 17-year-old Kathryn, 11-year-old twins Hilary and Ruth and 9-year-old Joe -- may as well have been. They had no phone (except for one in a locked room, to be used only in case of fire or medical emergency), no car, no TV, no fast food, no computer, no emollients. They did have whalebone corsets, chamber pots, toy soldiers made out of lead, bicarbonate of soda instead of toothpaste, a straight razor instead of a Gillette and a lovely, dusty sitting room.

In the first episode, the house was restored and the Bowlers were plucked from suburban obscurity and given instructions in how to light gas lamps, lace up corsets and keep the combination kitchen stove/boiler going. In episode two, "A Rude Awakening" (running Monday at 9 p.m.; check local PBS listings), the Bowlers move in, brought to their new home in a horse-drawn carriage while their curious neighbors line the sidewalk. After the giddiness wears off, reality hits. As the series unfolds, Paul cuts his face to ribbons with the straight razor, Joe refuses to eat the bland, gloppy food and the stove doesn't make enough heat to provide hot water for baths or to cook food all the way through. Joyce and Kathryn have to make their own sanitary napkins out of cloth "folded like nappies," because tampons weren't invented until the 1920s. A Maytag-less laundry day is a harrowing affair that involves boiling the clothes, agitating them by hand and putting them through a ringer; Joyce's hands are rubbed raw when it's done. (Take that, you "Survivor" panty-waists!)

By the middle of the second episode, the usually cool-headed and dryly witty Joyce is having a meltdown; she storms out into the garden after fixing another disastrous dinner (it's very hard to be a 1990s vegetarian in Victorian Britain) and screams at Paul about her "three rotten days" in the 1900 House. Then one of the twins sneaks off to tell the video camera that "Mum and Dad are shouting at each other ... If they don't just grow up, I don't know what we're going to do!" And comely Kathryn reaches her breaking point, too, over the lack of hot water and the disgusting, waxy, homemade shampoo she has to use. "I'm fed up with being dirty and smelly and greasy and skanky!" she whines to the video diary camera. Indeed, it's not long before the Bowler women sneak one unauthorized purchase -- a bottle of shampoo -- into their basket at the grocery store.

"The 1900 House" is classy voyeurism; it owes less to "Survivor" than it does to that seminal PBS reality series "An American Family" -- in which the social upheaval of the early '70s quietly tore an upper-middle-class suburban family apart before we even realized what was happening. Watching "The 1900 House," you get a vivid sense of the drudgery of life at the turn-of-the-century and the desperation that launched a thousand modern inventions. But more than that, you're transfixed by the Bowler family dynamics, by the mood swings of a family under pressure from without and within. They start out a nice, cheery, close-knit bunch, full of good humor and adventurous spirit. School inspector Joyce volunteered them for the project because she wanted to "time travel" back to her great-grandmothers' era, and Paul, a telecommunications specialist with the Royal Marines, went along like a good sport as "payback" for Joyce's putting up with the constant relocating his career demands.

But as Joyce bears the brunt of the domestic hardship in the 1900 House, she comes to realize what it means to be "stuck in a boring, mind-numbingly boring existence," and her frustration casts a pall over the household. Having agreed to take a leave of absence from her job for the duration of the series (because a turn-of-the-century woman of her class would not have worked outside the home), Joyce laments the "wasted talent and brainpower" of Victorian women. "This whole experience has just taken me up and it's shaken me right to the core of my being!," she cries.

Joyce snaps at Paul, begins researching the women's suffrage movement, buys a bicycle to gain some freedom and admits that she resents her husband for being able to leave the house and go to work every day (albeit, in a Victorian-era Royal Marine uniform). She also finds a small but satisfying way to rebel against the constraints of her prim and proper clothing. "I'm not wearing any drawers," she tells the video camera matter-of-factly. "I don't think Victorian women would have worn them every day. It would have been too much to wash."

Paul, for his part, seems to enjoy his role as master of the house. He's too much of a modern nice guy to lord over his wife and children, but he scarily role-plays the class superiority thing in his dealings with Elizabeth, the scrappy "maid of all work" Joyce has hired (in keeping with the practices of middle-class women of the time). Elizabeth is a saucy supporting player and tells the camera in no uncertain terms that she thinks Paul is a big jerk.

The most affecting part of "The 1900 House" is watching the Bowlers come together and make the best of their stay. Paul gives Joyce a sweet birthday surprise, the twins throw themselves into Victorian girl activities, like making puppet shows and taking photographs with a turn-of-the-century camera, and Kathryn, forced into the tedium of being an ornamental young lady of 1900, eventually learns to laugh at her imprisonment, becoming her mother's confidante and a budding suffragette. "We didn't realize our children were this confident or this resourceful," says Joyce, with pride and wonder. "I'm seeing them in a completely different light."

But in this summer of "Survivor," what really stays with you about "The 1900 House" is the lesson the Bowlers learn about the difference between true hardship and mere artifice. The Bowlers were not actors playing around on a set decorated with Martha Stewart Victoriana. They slipped into their ancestors' skins and felt Victorian society literally suffocating and chafing them, and their experience makes you understand why life, particularly for women, had to change. "It's not romantic. It's dirty. It's hard work," says Joyce. What did the Bowlers win for their three months of "primitive" living? Not a million dollars. Not anything material at all. But something else: "We take so much for granted these days, we don't actually realize how much has happened in the last hundred years," Joyce says. "For me, nothing will ever be the same again."

Shares