FACTS

Jude Law was born at the tail end of 1972, one of the most sexed-up years in popular movie history: "Deliverance," "Cabaret," "Deep Throat," "Last Tango in Paris." As a young man, he starred in a popular British soap opera before finding fame on Broadway opposite Kathleen Turner in Jean Cocteau's "Indiscretions." He spent most of the first scene of the second act naked in a bathtub. Obviously, he was nominated for a Tony.

Throughout the 1990s he gave notable performances in films of various quality: "Wilde," "Gattaca," "Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil," "Existenz," "The Talented Mr. Ripley." One of these, "Existenz," is a masterpiece, but it was "Ripley" that nudged him onto the Hollywood A-list, and earned him an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor. (Sheer madness that Miramax didn't secure him a win over Michael Caine in "The Cider House Rules.")

At the start of the new millennium, he played a gangster ("Love, Honor, and Obey"), a sniper ("Enemy at the Gates"), and a robot built for sex ("A.I.: Artificial Intelligence"). Now he is ubiquitous. Six major movies in 2004 -- "Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow," "I Heart Huckabees," "Alfie" and the upcoming "Closer," "The Aviator" and the animated "Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events," in which he contributes the voice of Lemony Snicket -- cover stories on all the big glossies, a ranking (his second) on People magazine's "50 Most Beautiful People" list.

"He has beauty with an edge," said Anthony Minghella, the man who made him a superstar. "He's unbearably handsome."

PHYSIQUE

Jude Law is lithe, agile, quick at the ankle; in "A.I.," he is consciously imitating both Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire. Excepting his creepy baldness in "Road to Perdition," his hair is a dense mass of dirty gold curls. In "Existenz," the passage from mundane reality to the excitements of virtual reality is signaled by an increased buoyancy of his coif.

Beneath two perfect parabolic eyebrows sit the virtuoso eyes, ready with fire or ice. His eye work in "Ripley" is a bright metamorphic tour de force -- from sparklers to sponges to a Medusa stone curse. Under the eyes, however, there are always bags, often dark -- a flaw! As early as "Wilde" they are prominent, lending a smear of the louche, a hint of the hangover, a possible sign of depleted dopamine (from last night's exertions?). The "A.I." makeup department managed to take all the color out of them, but the puffiness can still be detected. His eyelids have a tendency to rapidly flutter under stress or excitement.

When enraged or singing, his mouth becomes weirdly too large and round -- a distortion of his otherwise immaculate proportions.

He is of average height. His torso is unusually hirsute for a pinup of his kind.

FLAIR

In the biopic "Wilde," Jude Law plays Lord Alfred Douglas as a piece of erotic statuary that occasionally explodes into petulance, and his introduction to Oscar (Stephen Fry) is the most dazzling entrance of his career. The premiere of his "Lady Windermere's Fan" has just brought down the house. Oscar (and the camera) are drawn toward the mesmeric lad, who responds with a nearly imperceptible tilt of the head. Otherwise he stands firm, blazing challenge from his sapphire eyes.

"You draw blood," he compliments the chubby wit. "It's magnificent." (Law's three most commanding verbal acts in the film are his pronunciations of "superb," "delightful" and "magnificent.") Then comes a spellbinding monologue made of flattery, harangue and narcissistic fit. He spins through a rapid pinwheel of effects, a brilliant burst of moods: avid, caustic, impudent, enthusiastic, dismissive, impish, smug, self-pitying, vulnerable, aloof, more -- all at once. Both Wilde and "Wilde" never quite recover.

Here, in a film so middlebrow it's unibrow, Jude Law establishes the parameters of his future personae: the fusion of narcissus, Peter Pan and the Dionysian dandy; the whiplash shifts in register, from fury to glee; a rare talent for pregnant immobility (c.f. "A.I." and Rilke's "Archaic Torso of Apollo"); arresting physical beauty; sly sexual ambiguity.

WILDE AT HEART

In "Bent," a fantasia on the persecution of homosexuals during the Holocaust, Jude Law is among the revelers at a transsexual performance art disco orgy. Above his head, Mick Jagger in drag croons from a trapeze. Across the room, Clive Owen is doing bumps of cocaine with a hot blond übermensch. Law is on-screen for less than three seconds. He wears an eye patch.

Butch Clint Eastwood casts him as the (one-eyed) serpent in his "Garden of Good and Evil" -- the hothead hustler who undoes paradise.

In the vaguely homoerotic "Gattaca," he represents genetic perfection: "IQ off the register, better than 20/20 in both eyes, and the heart of an ox." Unable to cope with the pressure of being flawless, he has thrown himself in front of a moving vehicle and landed bitterly in a wheelchair. The joke of the movie, an overdesigned cautionary sci-fi parable, is that Ethan Hawke is his genetic inferior, and must borrow Law's skin flakes, stray pubes and urine samples to sneak his way into a superselective astronaut program. Chilly Uma Thurman plays the nominal love interest, but the real intimacy is between Hawke and Law, bonding over the byproducts of superior male physique.

In "Existenz," his character becomes actively (hetero)sexual only after allowing a pseudo-anal "bioport" to be installed in his lower back. This allows for the insertion of a fleshy, nub-tipped umbilical cord, necessary for playing Existenz, an avant-garde virtual reality game (otherwise known as "cinema"). "I have this phobia about having my body penetrated -- surgically -- you know what I mean," he says. But, "Once you've ported," says costar Jennifer Jason Leigh, "there's no end to the games you can play." She sticks a finger in her mouth, covering it with saliva, and inserts it in his bioport for lubrication.

CHEEK

Like the baboon, Jude Law often presents his hindquarters during courtship. When John Cusack first spies him in "Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil," he is hunched over his Camaro, ass offered up in tight jeans (the entire movie is thick with queer sizing up). In "Cold Mountain," Nicole Kidman discovers him up in the rafters of a church. As he climbs down to accept her glass of iced tea, he does so, naturally enough, ass first. Director Minghella sneaks in a distinct shot of her checking out his butt before averting her eyes.

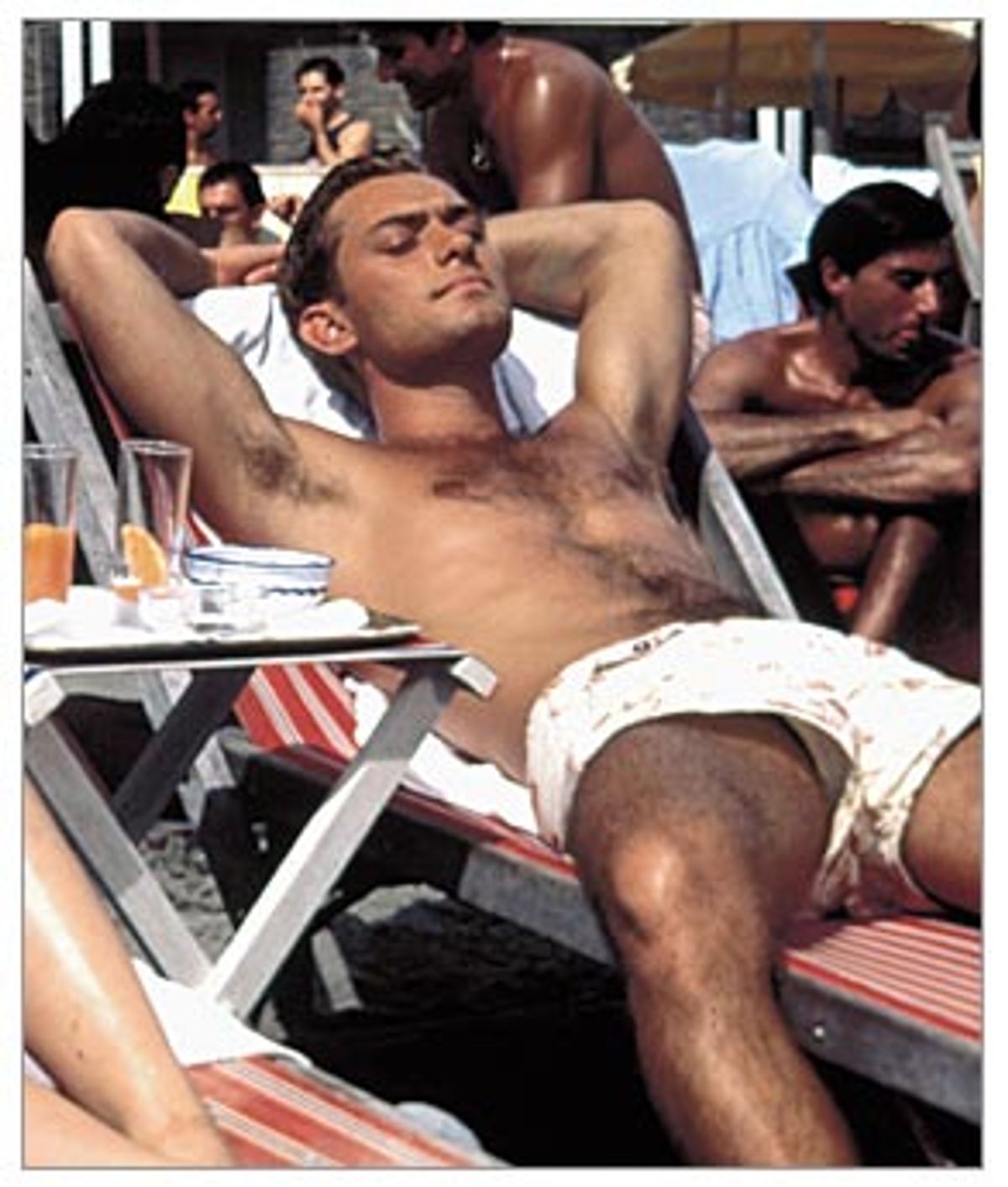

The talented Mr. Ripley (Matt Damon, an audience surrogate) goes utterly agog at the sight of Dickie Greenleaf rising, supple and glistening, from the bathtub -- a vision of Aphrodite rising from the sea, Narcissus reflecting in the bathroom mirrors. (Their first meeting is a warm-up to this encounter: Dickie insouciant on the beach, baring a manly open armpit to pale, timorous Ripley.)

HEY JUDE

The pop-punk band Brand New has recorded a song called "Jude Law and a Semester Abroad." While ostensibly addressed to a girl (androgynously) named "Jess," the lyrics might well have been written by Belle and Sebastian. A man's voice sings:

So here's a present to let you know I still exist

I hope the next boy that you kiss has something terribly

contagious on his lips

...

Tell all the English boys you meet

about the American boy back in the states

The American boy you used to date

who would do anything you say

...

And all this empty space that you create

does nothing for my flawless sense of style

Still, Jude Law claims to have been named after a Beatles song:

"Hey Jude, don't be afraid. You were made to go out and get her. Na na na na na ..."

ONE HECK OF A MECHA

"Is this your first time -- with something like me?" One can imagine Jude Law saying this to almost everyone he takes to bed. In this case, he says it as Gigolo Joe, the synthetic stud who befriends the wee robot hero of "A.I.: Artificial Intelligence." Law refines the talent exhibited in "Wilde" for instantly becoming objectlike, eliminates his tendency to eye flutters; moreover, he (almost?) never blinks in the movie. His DVD commentary explains the concept: "Rather than make a false me, it was to make me false." Spielberg gets to something crucial about Law: He projects an idea of perfection.

Law is truly glamorous, in the etymological sense: He enchants. His spell -- the vital thrust of his pluck, his unassailable élan, his scintillation of eye, his superior wardrobe and makeup crews -- clouds up the mind. Flaws are dwarfed by sheer aplomb.

David Cronenberg (with "Existenz") goes deeper than Spielberg: He uses Law as something indeterminate, a fluctuation, a vibrating potentiality. He first establishes "P.R. nerd" Ted Pikel as a reluctant hero/straight man inadvertently caught up in the machinations of a sci-fi thriller. As the movie becomes a genre head-trip (richening, wonderfully, into a metaphysical comedy about storytelling), Pikel gains confidence in the plot, becomes the self-aware movie star of his own narrative. Law is exceptionally sly in expressing his modulations of self-consciousness, the constant measuring of slippage and gain in the game play of his own heroism. "I feel just like me!" Pikel marvels on his first trip into Existenz. (The movie makes a case for Law as an underestimated comedic actor.)

MINGHELLA THE MERCILESS

In "The Talented Mr. Ripley," Minghella unleashed all of Jude Law's ferocious sex appeal and terrifying confidence; in "Cold Mountain," he smothered these qualities under mangy facial hair and rhetorical (delusions of) grandeur. Both films earned the actor Oscar nominations. For the former, he deserved it.

As Dickie Greenleaf, expat black sheep of the Greenleaf shipping fortune, Jude Law cavorts through an imaginary Italian utopia. Bronzed, shirtless, in pink shorts and white sneakers, he darts over cobblestones on a Vespa, pausing to sip Campari and impregnate the locals. He is the consummate clotheshorse, peacock, cock tease, bon vivant, solipsist. A big prick too, as lady friend Marge (pouty Gwyneth Paltrow) explains. "The thing with Dickie, it's like the sun shines on you and it's glorious. And then he forgets you and it's very, very cold. When you have his attention you feel like the only person in the world. That's why everybody loves him."

Everybody loves Jude Law for what he puts into Dickie: velocity, glamour, enviable arrogance, poise supreme. An inspired line delivery: "I really want to move to the North." Law nails the useless scion who equates a change of villa with a momentous life decision.

"Cold Mountain": an arduous climb; the only movie in which Jude Law gets dirt under his fingernails. In this picaresque Civil War romance, he is everywhere upstaged by production values, helicopter shots, character actors. Early on, getting his woo on, Inman (Law) says to Ada (Kidman), "This doesn't come out right. If it were enough just to stand, without the words ..." Indeed. Law is best here not speaking at all, but simply in motion, striking poses, mutely Oscar-grubbing his way through the Southern landscape (Romania, actually). The reunion with Ada plays like two ice sculptures trying to make each other melt -- in a way more frigid and kitschy than Minghella intends. Is he the stuff of leading man-dom? The Academy thinks so, as does "Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow." (Jude Law was in that? All I remember is robots.)

THE M WORD

Confident in his megastardom, Law now takes on roles that "expose" his falseness, crack his surface. In "I Heart Huckabees" he is a soulless corporate suit who undergoes a spiritual strip down at the hands of David O. Russell's frenetically banal schema. In "Alfie," the worst gender-flipped episode of "Sex and the City" ever, he's a metrosexual monster in Margiela. His mush-headed deconstruction (by the director of "Baby Boom" and the writer of "Murphy Brown") reveals a man-boy cuddly-wuddly in a cable-knit cashmere hoodie. Aw. These are flimsy reckonings with a persona, one of the steeliest in contemporary movies.

BUT(T) BRILLIANT, THIS:

In Martin Scorsese's "The Aviator," Jude Law will play Errol Flynn.

Shares