"Hart's War" opens with a fast, tense sequence that leads you to expect you're in for a gripping World War II escape drama. Thomas Hart (the opaque and earnest Colin Farrell), a young lieutenant spending the closing months of the war working Army intelligence in Belgium, offers to drive another officer back to his infantry. On the way, they're intercepted by a German trap and Hart is taken prisoner.

Although the sequence contains the by now expected quota of combat gore (the officer's brains are blown out all over Hart's face), and though it sets the tone for the unrelieved grim humorlessness that follows, the director, Gregory Hoblit ("Primal Fear"), shows some sense of narrative economy in detailing Hart's capture, interrogation and march to a prisoner-of-war camp. The cinematographer, Alar Kivilo, shoots the wintertime European landscapes as vast gray-blue expanses, and he conveys the punishment of the climate through the simplest means. There's an impressive long shot of a line of prisoners slowly trudging across the screen. And another shot focuses on a group of dead American soldiers lying in a ditch, a light frosting of snow just beginning to obscure their features.

"Hart's War" eventually winds up genre-hopping from POW drama to courtoom drama to escape drama, elements that never feel as if they all belong to the same movie. And while there have been plenty of war movies that provided breast-beating affirmation of duty, honor, sacrifice without humanizing any of those concepts, "Hart's War" affirms the old military crapola of WWII combat movies in a singularly odd way.

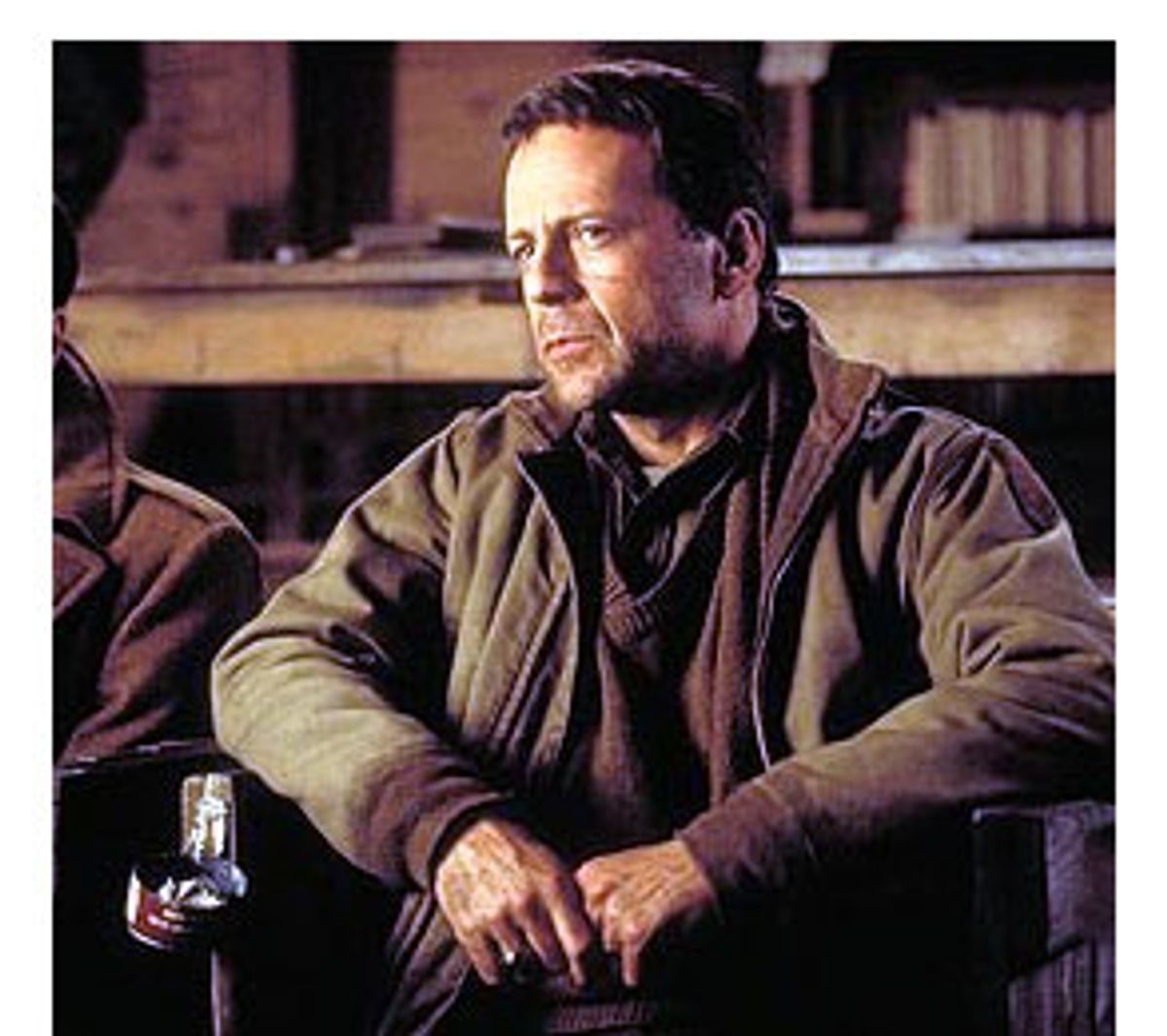

I stayed with the film for a while because it looked like it was about to overturn the clichés of '40s war movie propaganda. At the POW camp, Hart arrives to see the Nazis hanging Russian prisoners who have tried to escape. When McNamara (Bruce Willis), the Army colonel in charge of the captured Americans, protests the hanging to Visser (Marcel Iures), the ranking SS officer, Visser tells him the men were dogs. Hart pumps himself up to say that Americans don't make those distinctions about human beings.

It's a rah-rah moment tested by a pair of new prisoners. The two are Archer (Vicellous Shannon, who plays Dennis Haysbert's son on that weekly heart attack of a show "24") and Scott (a a credible, understated Terrence Howard), two black Tuskegee airmen. McNamara refuses to let the black fliers bunk with the officers and assigns them to the enlisted men's barracks. There, the new arrivals find themselves at the mercy of the heavy-browed racist Bedford (Cole Hauser, who apparently never met an acting trick he didn't like), a former Southern cop who refuses to acknowledge that the black men outrank him, and who taunts them and plants contraband on them to get them in trouble.

The contradiction between the stated goals of American warfare and the treatment of black soldiers in the U.S. military is a great subject that hasn't been dealt with as fully as it could be in the movies. (There are exceptions, such as the stirring Civil War drama "Glory," and John Irvin's conflicted, and now forgotten, Vietnam film "Hamburger Hill.") "Hart's War," which takes place four years before President Truman's order to desegregate the armed forces, doesn't say that America was in no moral position to condemn Nazi brutality. But in its early scenes it does say that while fighting fascism in Europe we had yet to deal with our own homegrown fascism toward African-Americans. That's a neat reversal of the war movie device of showing the "melting pot" platoon coming together to defeat a common enemy, and it could have been the basis for a drama that would have been, in the best sense, unresolvable. But "Hart's War" starts out by appearing to question military justice, and ends up as a recruiting poster.

When the racist Bedford is murdered, Lt. Scott is charged. The SS wants to execute him on the spot, but McNamara talks Herr Visser into letting the Americans hold a court-martial to determine Scott's guilt or innocence. The trouble is there seems to be no way he can get a fair trial. He doesn't even have adequate representation. Hart is assigned as his lawyer, even though he hasn't finished law school. His tactics to cast doubt on Scott's guilt keep backfiring, and it looks like Scott is headed for a firing squad. Hart finds an unlikely ally in Visser, who slips Hart a copy of U.S. court-martial procedure so Hart can challenge McNamara's authoritarian rule of the court.

Visser's motive seems obvious: to embarrass McNamara, the ranking American officer. But he's a little more complex. Like Hart, Visser is a Yale man (a nice touch), and during his years in America, he picked up a fondness for "Negro jazz," which, though verboten, he listens to in his study at night. Marcel Iures, whose role starts out as that of the token, sneeringly cultivated Nazi, relaxes a bit in these scenes, bringing the movie some needed stray bits of irony. It's not beyond the pale to imagine that there were German officers who, though attracted to Hitler's plan of world domination, fond his racial policies cracked, even as they carried them out.

Then "Hart's War" takes a nutty turn. As the action draws to a climax, "Hart's War" turns into a pissing match to see which character can outdo the others' dedication to sacrificial duty. It's a little like watching a Monty Python sketch played at the wrong speed, with a bunch of soldiers pushing each other aside to be the first one to go "over the top."

"Hart's War" really takes leave of its senses, though, when, after Hoblit and screenwriters Billy Ray and Terry George (working from John Katzenbach's novel) have spent the movie portraying McNamara as a villain out to frame Lt. Scott, they turn around and make him the hero. He's the one whom Hart, inexperienced in combat and privileged (he's a senator's son), has to look up to in order to learn what it means to be a soldier. And what McNamara deems being a soldier is a ruthlessness that any fascist army would be proud to call its own. He's the absolute worst sort of army officer, one who is so fixated on the cause that he never gives a thought to the consequences. And the consequences of his plan here are clearly getting more of his men killed than he keeps alive, though in a POW camp that's the exact opposite of what his duty should be.

The most unremarked aspect of Susan Sontag's infamous post-Sept. 11 New Yorker essay was the machismo at work in her thinking. Her definition of "courage" -- or, to adopt her sophistry, what it meant to not be deemed a coward --- was essentially the old he-man garbage of equating courage with physical bravery. She might salute "Hart's War," where the young intelligence officer doesn't become a worthy part of the war effort, doesn't become a man, until he's beaten and tortured and learns to salute reckless (and here, pointless) physical daring. What about the intelligence officers and code breakers who weren't exactly incidental to Allied victory?

The unwitting irony of "Hart's War" is that the final act of violence, which we're meant to shed tears over and see as a noble sacrifice, is what any American military court in its right mind would do. Hoblit has succeeded in taking an alternate view of WWII -- just not the one he intended. He's made a movie where the Nazis have more of a sense of justice than the Americans.

Shares