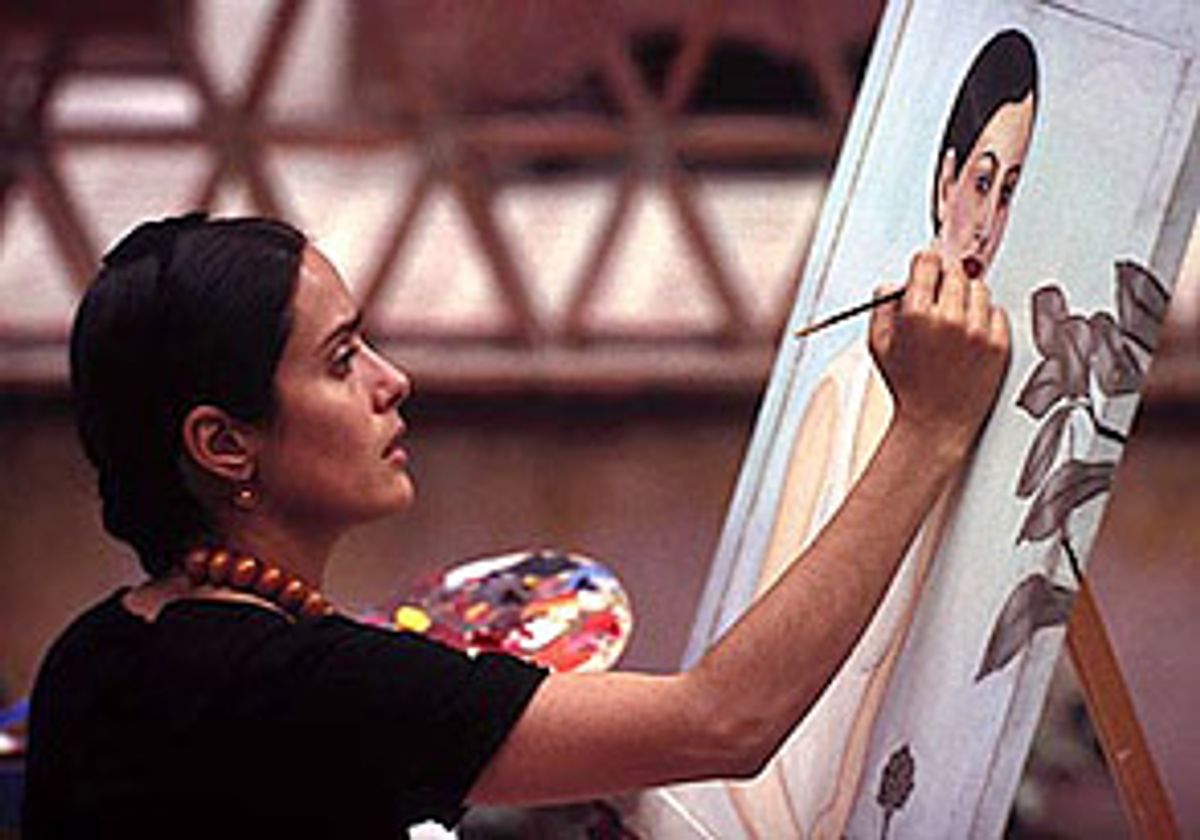

The "long-awaited" "Frida" comes to the screen with alarming attributes: eight writers and no less than 16 people serving as some kind of producer. Well, yes, it is hard to make a motion picture, but generally it is harder still if you have that many people competing for credit. Admittedly, there is only one director, Julie Taymor, and only one person playing Frida -- Salma Hayek, who is also one of the producers. A lot will be said, quite properly, about the determination with which Ms. Hayek got this film made, as a burning passion, a labor of love, a life's dream, etc. Such things are all very well, and worthy. But they do not find a way past this conundrum: Salma Hayek is one of the most beautiful people on the modern screen, and Frida Kahlo did not look like that.

The platoon of executives on "Frida" signals how many people have wanted to make this picture -- and it also inadvertently indicates the common fallacy that great or celebrated lives are made for the movies. Frida Kahlo was a woman and an artist, and in recent years there are those who find that concurrence so intoxicating they're ready to greenlight a picture deal, without realizing that a life is not always a story. Frida knew famous people -- Diego Rivera, Trotsky and Tina Modotti (possibly a finer artist, as well as a more interesting life). Frida strove against handicap: As an adolescent, she suffered a drastic accident that damaged her insides and scarred her for life. I can believe that she was sexually active nonetheless, but I think it's clear that she was just as obsessed by physical pain (her most faithful lover and companion, perhaps).

Frida often painted herself, which is a problem for any biopic because if the movie is to use the paintings then it is obliged to hire an actress who at least resembles them. Years ago, it was a great coup in "Lust for Life" that Kirk Douglas looked a lot like Vincent van Gogh. But "Lust for Life" was a very melodramatic, sentimental view of the artist. I think it is a safer rule that the best biopics (and it is a very vulnerable genre) start with actors who do not resemble the subject. Only then can the story start. I suspect that Ed Harris was drawn to Jackson Pollock in the first place because he reckoned they looked alike. Well, in a way. But that bit of luck is nothing if the actor doesn't understand the painter, and if the artist's life is as messy and inconsequential as Pollock's.

I daresay Salma Hayek loves Frida's paintings and the idea of the real woman as a heroine of her times -- a Latina who refused to settle for the passive role Mexican society required for women. But there are moments in "Frida" (in a big motion picture with Salma Hayek there have to be), when the actress shrugs off her clothes and engages in the antics of love and sex. These are stunning moments. Salma Hayek is a dream of carnality, radiant in the sun-drenched color scheme that Julie Taymor has employed. Alas, it is so much a body made of peaches and cream that one never feels the pain in the body. And this Frida Kahlo has no mustache.

I seek no point about hormones, sexuality or personality in referring to the mustache. I am not interested in how far it does or does not affect conventional attractiveness. But I have seen enough photographs to know that the real Frida Kahlo had a silky black mustache. And I have to guess that Hollywood and even the valiant Ms. Hayek decided that that was a no-no.

Why? The question intrigues me all the more in that I read recently about how John Ruskin (1819-1900), the English art critic, probably failed to consummate his marriage because of his horror at discovering that his wife had pubic hair. Ruskin was richly educated. He had a fine mind and an exceptional sensitivity. He was accustomed to the nudes of art that were flawless -- i.e., the women had hair on their heads only. Literally, he did not know in advance that women have pubic hair. Thus, his profound aesthetic bumped into the tangle of reality.

The movies nowadays take pubic hair for granted, though as I recollect, in "Frida," Salma Hayek keeps one gorgeous thigh folded over the other, so not too much shows. But pubic hair is eroticized in much the same way that the flow of a woman's long hair is a metaphor for passion. So why can't Hollywood live with some facial hair? Why does some semi-religious horror remain about the prospect of beauty with a mustache?

There is a great painting by René Magritte in which the outline oval of a woman's face is filled in with the beard and mustache of pubic hair. I suppose its shock value is at least as disturbing as it is arousing. Yet we have come to terms -- men, I mean -- with pubic hair, with armpits full of hair (I recall the 1963 Joseph Losey film "Eva," in which Jeanne Moreau had not shaved her armpits, and the feeling of liberation). Isn't the idea of a woman needing to find a private place where she can apply a razor edge to her own natural private places absurd and alarming?

"Frida," we will be told, grew out of a deep respect for the "real woman." Yet all the writers and producers couldn't let the truth on her upper lip show.

Shares