When a movie by a fledgling director with no major stars goes into theaters at the same time as the prestige Christmas releases, it's practically guaranteed to disappear. But "Drumline," which is still in theaters a few weeks after opening, has actually managed to find an audience amid all the big-deal releases competing for your attention.

The script for this drama about a marching band at a predominantly black Atlanta college, by Tina Gordon Chism and Shawn Schepps, rarely rises above the conventional and serviceable. But the direction, by Charles Stone III (who earlier last year directed the hip-hop drama "Paid in Full"), gives the movie its distinction. When a young director, working in the mainstream, shows this much craft in only his second feature, and when he's so resistant to the stylistic clichés of the genre he's working in (for want of a better distinction, call it a "youth" movie), it's a good bet that he's headed for impressive things.

At one time in Hollywood, the sort of "invisible" craft at which Stone is so adept wouldn't seem like a big deal. It was part and parcel of a competence that -- at minimum -- directors were expected to have. Now, when there's no assurance that a Hollywood movie will have a story that even makes sense, or attempts to define -- let alone explore -- its characters, Stone's talent is a big deal. He's proof that mainstream movies can find an audience without being the same old big-budget crap that favors sensation above everything else.

The story is basic. Devon (Nick Cannon), a talented drummer from a Harlem high school, wins a full scholarship to play in the marching band of an Atlanta college. Cocky and with a forest-size chip on his shoulder, Devon cannot submerge his identity to fit into the group's credo of "one band, one sound." Of course, the movie is about how he learns to put his talent to the use of his fellow band mates. And along the way there's a believable and unforced romance with Laila (Zoë Saldana), an upperclassman on the cheerleading squad. If that conjures up images of short skirts and rump shaking, think again. Stone doesn't shoot Saldana as a hoochie mama. Laila is smart and makes Devon work for her respect. Saldana's performance is only the most typical example of the way Stone doesn't force his actors into playing stereotypes.

I'll admit to having one problem with "Drumline" that may have more to do with my sensibility than any fault of the movie. As run by its director Dr. Lee (Orlando Jones) and its student leader Sean (Leonard Roberts, probably most familiar as Forrest, a few seasons back on "Buffy the Vampire Slayer"), the band operates with military-like discipline. That involves verbal abuse, humiliation, even a hint of sexual harassment -- in short, the sort of bullying that makes me long to see the bullies get theirs. We're meant to see Devon's refusal to submit as proof of his cockiness, and God knows something needs to knock the smirk off this kid's face. But his resistance feels like his way of maintaining his individuality and self-respect. As in every movie I've ever seen featuring a drill instructor, for much of the first section of "Drumline," I would have been happy to see Devon land his boot in the asses of his tormentors.

But of course the point of the movie is that that wouldn't get him anywhere. There's a conservatism at work in "Drumline" that plays itself out in both Devon's behavior and in the cultural questions that the picture touches on, despite its limited script. Dr. Lee is under pressure from the college president to give the public what it wants, which means a lot of high-stepping flash and, musically, whatever faceless stuff is currently on top of the charts.

When a visiting team opens their routine with a rap tune, Lee, as proud as he is intransigent, has his band respond with "Flight of the Bumblebee" to prove that musicianship is not dead. It doesn't exactly set the crowd's toes a-tapping. Lee insists he's providing an education for the band members under his tutelage. That touches on a bigger question, for both black culture and all of pop culture: Does the sampling that is now the norm in hip-hop and dance music reflect a retreat from craft, or is it simply a different kind of craft, one where the emphasis is on rappers and producers rather than instrumentalists?

You can understand why a musician like Dr. Lee would choose the former answer. But the movie comes down on Lee's side of the equation, too. Press the argument too far in one direction and you'll find something close to the (black as well as white) commentators who have argued that hip-hop represents a degradation of black culture. The problem with those commentators is their unwillingness to make distinctions; they conveniently reduce all of hip-hop to gangsta-and-ho posturing. But giving all aspects of black culture a free pass (as some liberals might) is just as much a refusal to make distinctions. "Drumline" is bracing because it offers the rare spectacle of a mainstream movie actually addressing cultural questions.

Lee's insistence that he's giving the kids an education raises another question that the movie doesn't answer. "Drumline" shows the competition among college marching bands to be as fierce as the competition among their sports teams. The film even ends up at a big national marching-band competition with Devon and his teammates facing their arch-rivals. But we only see Devon studying once, and I began to wonder if he and the other band members who face a grueling practice schedule are exploited the way college athletes are.

Dr. Lee is scrupulous about making his musicians live up to the tough standards he sets for them -- no slacking off and no playing favorites. But when the movie raises the issue of the college administration demanding that the marching band win championships in order to spur alumni donations, and when Lee demands as much from the musicians as he does, it's not untoward to wonder if the college isn't willingly allowing academics to take a back seat.

But there's no way of getting around just how well-made "Drumline" is. I've already said that Stone avoids the clichés you might expect in a youth movie. In the most obvious terms, that means there's no fast editing, and he doesn't allow soundtrack music to substitute for narration or character development. The movie could stand to be about 15 or 20 minutes shorter, but in individual scenes Stone's sense of timing feels just right. The editing, by Bill Pankow and Patricia Bowers, often seems to break off a scene before you expect it to end. What hits you on the rebound is that Stone doesn't extend scenes beyond their narrative or dramatic purpose. He imparts the information we need and moves on.

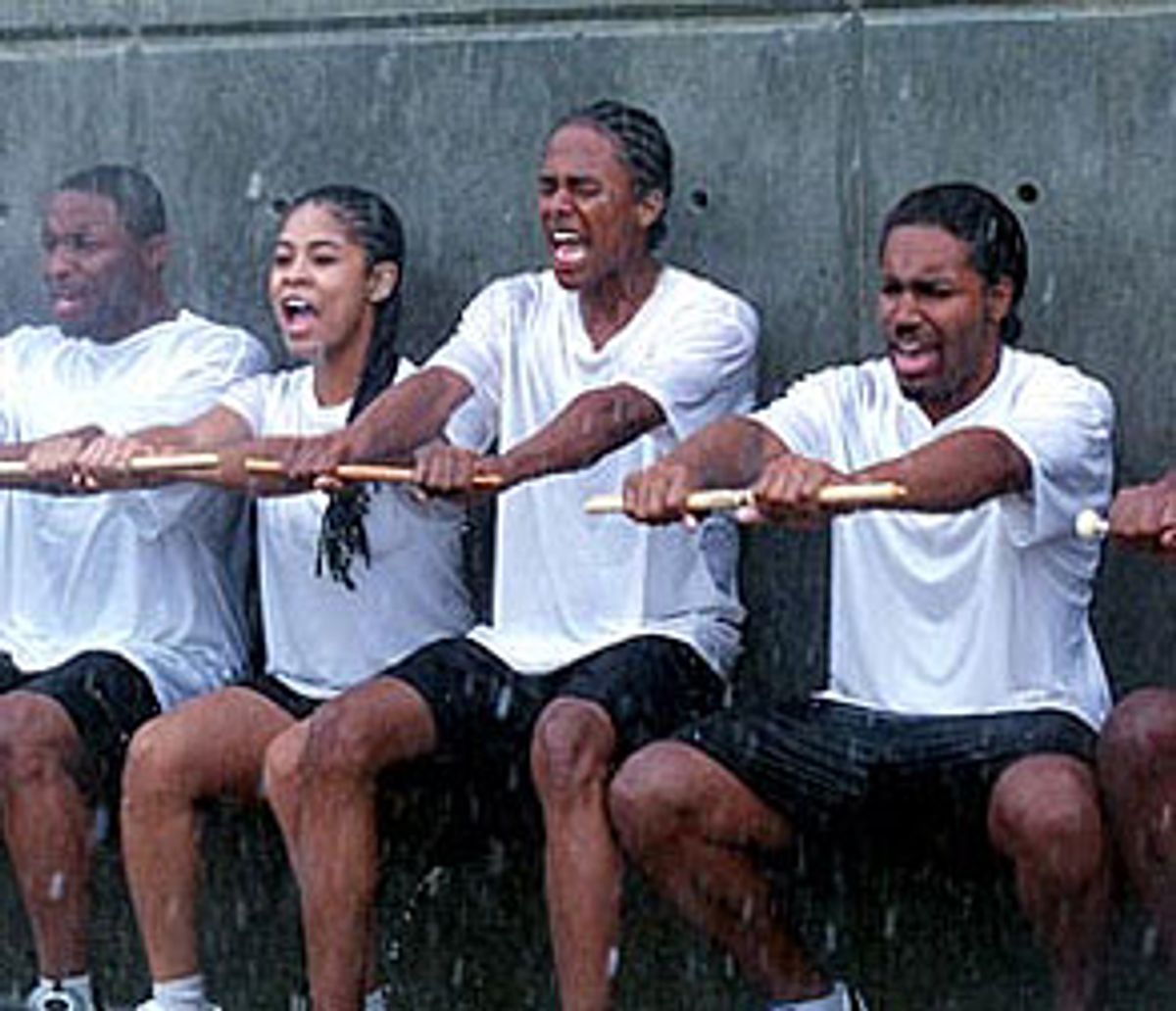

Stone also has a subtle but strong sense of composition. The cutting in the performance scenes is cued to the rhythm of the players and when the camera is floating up high, as the band practices its moves on the field, you can imagine Busby Berkeley watching somewhere, jealous that he never got his mitts on a marching band. The movie was shot by Shane Hurlbut and none of the shots call attention to themselves. Instead you're struck by the beauty of watching a row of drummers' hands as they blur with the rhythm their sticks are beating out. There are some lovely, misty shots of the band practicing in the early morning, and in the final scenes of the big competition, which takes place at night, in an outdoor stadium, with the darkness providing something like a 3-D effect, the players stand out as lone figures on the field.

Stone has a good, unforced way with actors. I mentioned his refusal to have his actors play black stereotypes. You see that in Orlando Jones' performance as Dr. Lee. Jones, whom you know as the "Make 7-Up Yours" guy, has been used primarily in movies as a lanky-limbed clown. Here he has an authority he has never been given a chance to demonstrate before. And Stone delivers beautifully on the main purpose of the movie: to allow us to experience the precision and beauty and the satisfying oomph of a great marching band. Maybe you have to have seen the great black Southern marching bands to understand how music most of us think of as stiff and martial can have swing. Stone gets that instinctively, and his movie more than does justice to its subject.

For months now, I've been bleating that a good number of the current black movies, even when they aren't successful, give the feel of being made for audiences instead of by committee. Maybe they aren't quite the politicized treatments of black culture and black identity that some viewers (white as well as black) want to see. But they provide black audiences the chance to see movies with involving stories where the black characters aren't sidekicks or multiculti window dressing, and they also suggest how black-made movies can cross the color line (as "Barbershop" did). To put it bluntly, I don't think most audiences give a damn about the color of the characters as long as there are characters -- and as long as a filmmaker has a good story and knows how to tell it.

"Drumline" isn't an important movie or a visionary piece of filmmaking, but I think it's important for moviegoers to pay attention to it. We need the visionary filmmakers and the wunderkinds. But most movies aren't visionary masterpieces, and it's not too much to ask that they be good and intelligently made. Right now, Charles Stone III is a craftsman with brains and taste, an instinctive sense of where to put the camera and the discipline not to belabor scenes. With more original material, he could turn out to be more than that. This is a talented young American filmmaker who bears watching.

Shares