Brian Moore's 1996 novel "The Statement" should be perfect material for a smart, tense movie thriller. Working in the same style as Graham Greene did in his "entertainments," Moore wrote a compact, pointed book about French complicity in crimes against the Jews during the Nazi occupation. The story focuses on Brossard, a former member of the Vichy regime's military police who has managed to stay hidden in France for years with the complicity of the Roman Catholic Church. The novel details Brossard's desperate flight as those who want to avenge his crimes close in on him, and as a judge and army colonel attempt to locate him before his would-be assassins do. This pair wants to expose those in the French government who are just as guilty as Brossard but who have successfully hidden their past.

The late Moore, who left his native Ireland in his 20s to escape the church's hold on all aspects of life there, is a pretty good argument for Greene's famous contention that no one understands evil like a Catholic. "The Statement" is a steely, measured attack on the Church's record against the Nazis. In one scene, an older priest tells a younger one, "One thing I will always believe is that we lost the war, not in 1940, but in 1945 ... In 1940, under Maréchal Petain [the leader installed by the Nazis], France was given a chance to revoke the errors, the weakness and selfishness of the Third Republic ... Under the Maréchal, we were led away from selfish materialism and those democratic parliaments which preached a false equality, back to the Catholic values we were brought up in: The family, the nation, the Church. But when the Germans lost the war, all that was finished."

For Moore, it made perfect sense that an authoritarian body like the church would find much to admire in Nazism. But he wrote "The Statement" with the controlled outrage of someone who, no matter how far he has removed himself from the church, has never escaped its notion of sin. He records the priests and higher-ups who sheltered Brossard mouthing their pieties about Christian forgiveness, and you feel Moore's disgust at what it is they are so willing to forgive. For Moore, the guilty clerics in his novel are stained by their willingness to rationalize the crimes of the past, and he writes as if to withhold his own absolution from them.

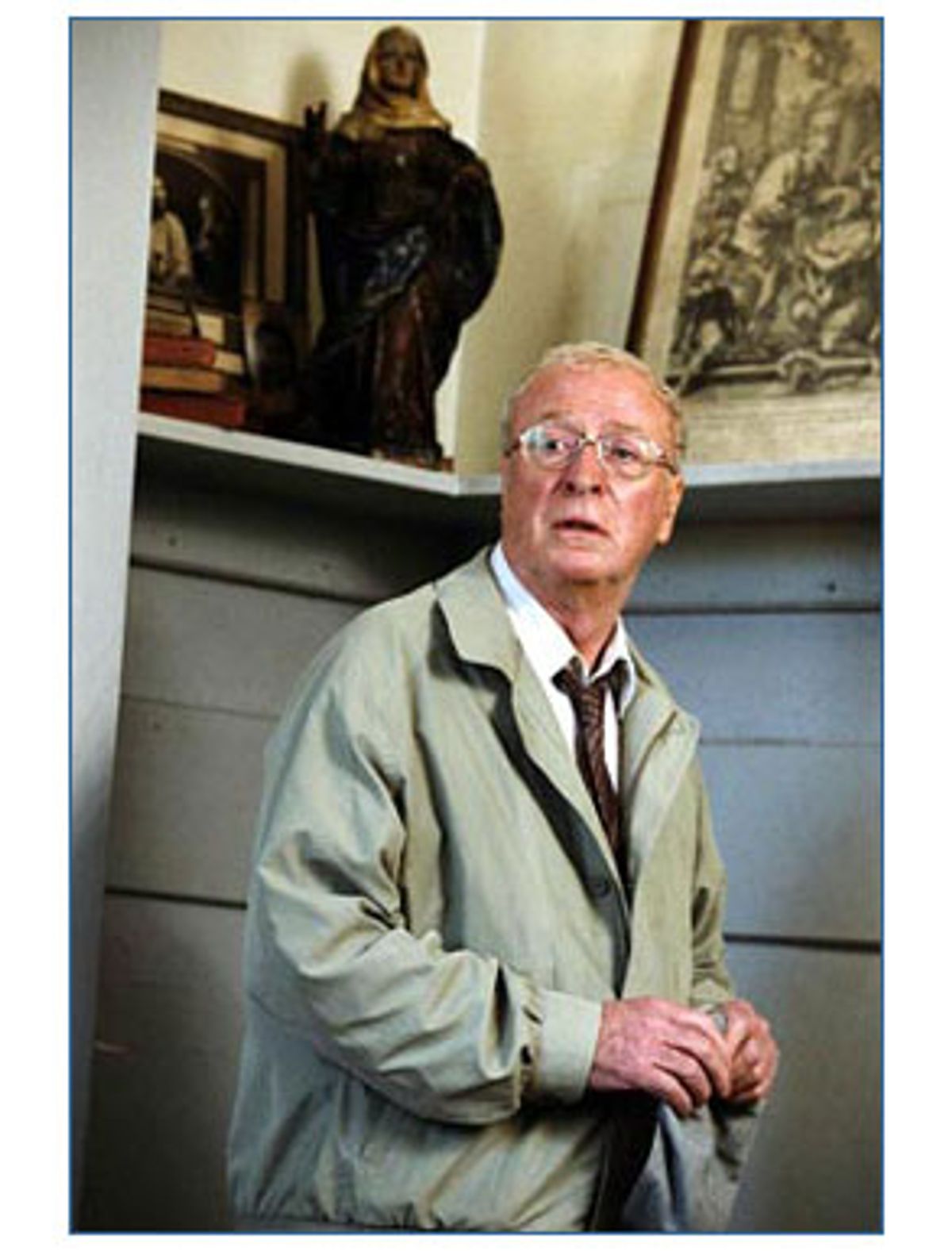

One would hope that a movie made from this novel might be a solid, exciting piece of muckraking that would stir up argument. The director, Norman Jewison, has always had an affinity for "social problem" pictures (never more entertainingly than in his 1967 "In the Heat of the Night"), and he's assembled an amazing cast. Michael Caine plays Brossard, Tilda Swinton and Jeremy Northam, respectively, are the judge and colonel tracking him down, and Charlotte Rampling, Alan Bates, Frank Finlay and Ciarán Hinds all turn up.

But "The Statement" is a stiff, clunky piece of work that never builds up urgency or tension. The script, by playwright Ronald Harwood, who wrote the script for Roman Polanski's "The Pianist," is close to atrocious, with nearly every line being a piece of exposition or a statement of the movie's themes. It's not so much that Jewison has worked to make sure the movie doesn't offend anyone (this material is bound to offend somebody) as that he proceeds mechanically, with half his attention on the machinations of the various factions hunting Brossard and half on the ideas of guilt and responsibility. We see a flashback to Brossard's major crime, carrying out the execution of French Jews, in progressive bits and pieces, and each time Jewison returns to it the impact is lessened.

Most of the time, "The Statement" is one of those deadly pictures whose individual scenes consist mostly of watching men in suits talking in a room. Something has petered out in Jewison's work. His previous picture, "The Hurricane," was another potentially involving piece of muckraking that got hung up in the subtext about fathers and sons. "The Statement" is even more remote -- and nobody connected with it seems to have noticed the strangeness of watching a predominantly English cast (Hinds is Irish) playing French people with English accents on location in France. (I giggled when Jeremy Northam donned one of those round, crowned hats worn by French officials, looking as if he were about to play Inspector Clouseau.)

No movie features a cast like this without providing at least some moments of good acting, though in each case it's about what the actors are able to do in spite of their material. I don't find it objectionable that the movie avoids the cliché of providing a romance between Northam and Swinton, but did that have to mean not even permitting them some nifty byplay? Northam, one of those actors it's always a pleasure to see, at least provides a few notes of dry wit. Swinton is less off-putting than usual. Maybe she's best in roles that require speed and impatience -- the sharpness of her features translates well in playing a character who has to think on her feet. Charlotte Rampling manages to get some poignancy into the small role of Brossard's estranged wife, a bedraggled proletarian cliché. The one all-out bad performance is from John Neville, whose dried-out, beady-eyed aristocratic air seems as inauthentic as always.

It's amusing to open the newspapers to the ads for "The Statement" and read Jeffrey Lyons proclaiming, "Michael Caine is a revelation!" It's taken 47 years of Caine's film career for Lyons to have a revelation watching him act? What has he been watching all these years? Caine is severely limited by the thinness and stodginess of the script, and in some ways he's miscast. Caine is basically too grounded and individual an actor to play a man so subservient. But he does something in "The Statement" that he's never done before: He convincingly plays weakness. Brossard's weakness isn't the heart condition that forces him to pop nitroglycerin capsules and huff and puff whenever he exerts himself. It's the weakness of the born follower, a man who willingly puts himself in the hands of authority, whether those of Vichy or the church.

Caine is well past the actorly vanity of caring whether or not he's likable. He gets at the servile clamminess of Brossard, and in a better movie the performance might be more than the sketch it is here. Caine is an actor who clearly loves to work -- even when he's given a mucked-up vehicle to work in. Coasting on his reputation and his built-up audience affection just doesn't seem to occur to him. His bag of surprises is far from empty.

Shares