Mike Newell's "Mona Lisa Smile" is a movie designed to make you think, which is precisely the problem: For a story about bohemian intellectuals circa 1950s New England, it sure is low on intellect. Julia Roberts' Katherine Watson is a free-spirited, sexually liberated, unmarried-by-choice art history professor who leaves her native California for a teaching position at that all-girl bastion of propriety, Wellesley College.

Katherine's students, as well as her fellow faculty members, are shocked to the very hem of their crinolines by her unorthodox ways -- doesn't she know it's not dainty to have a penis in your room after 10 o'clock? Bright as her students are, they're less thirsty for knowledge than they are hungry for an MRS. With a dazzling proto-feminist gleam in her eye, Katherine swoops in to change their thinking -- but not without learning a very important lesson about that most modern virtue, the one any contemporary toddler could explain to you but which was apparently beyond the scope of even the most rad-boho human beings in the 1950s: tolerance.

Tolerance, schmolerance -- what about the penis in the lady's bedroom? That's where "Mona Lisa Smile," which was written by Lawrence Konner and Mark Rosenthal, falls down on the job. The movie thinks it's telling us something new: Modern moviegoers will be shocked to learn that 1950s America was a restrictive time and place for women. (The truly sensitive creatures out there may want to cover their eyes during the terrifying montage of household-appliance and laundry-soap ads that runs behind the movie's closing credits.)

The problem with making a movie that's even gently damning of the restrictive qualities of the '50s is that moviegoers adore the restrictive qualities of the '50s, for good reason. Any anti-'50s rhetoric fed to us is going to be scooped up with a giant ice cream spoon: A stretchy hold-all for the things we modern Americans claim to have finally shed our taste for (safety, conformity, impeccable manners), the '50s are the decade we love to hate, the one that makes us feel most self-congratulatory about our groovy modern selves.

And yet we murmur to ourselves with a sigh: "Look at the clothes! The cars! Why can't Sony make a plasma-screen TV in a good-looking wood-grain cabinet like that?" And that's the pull that "Mona Lisa Smile" exerts: It's dishy and alluring in a way that works at cross-purposes with its themes. In fact, it would be a much more enjoyable and honest movie if it had no themes -- only actresses and costumes.

So my advice is to stride into "Mona Lisa Smile" without even trying to grab on to any of its sparse, free-floating brain molecules -- in other words, pretend you're the stereotypical '50s housewife the movie so desperately wants us to believe in, and relax and enjoy it. "Mona Lisa Smile" almost works as a women's ensemble drama along the lines of "The Group" or "Stage Door" (it's probably better than the former and not anywhere near as good as the latter). Even as I fumbled around to get a handle on its bony ideas, I found myself constantly wondering: What's going to happen next? Will Joan (Julia Stiles), the upright, brainy beauty, fulfill her dream of going to Yale Law School, or will she stick with her nice, but not exactly progressive, boyfriend? Will Betty (Kirsten Dunst), the smug one who's always announcing loudly how engaged-to-be-married she is, find happiness with a washer, a dryer and a blob of a husband? Will Connie (played by the dazzling Ginnifer Goodwin), the supposedly "chubby" one, find a boyfriend at all?

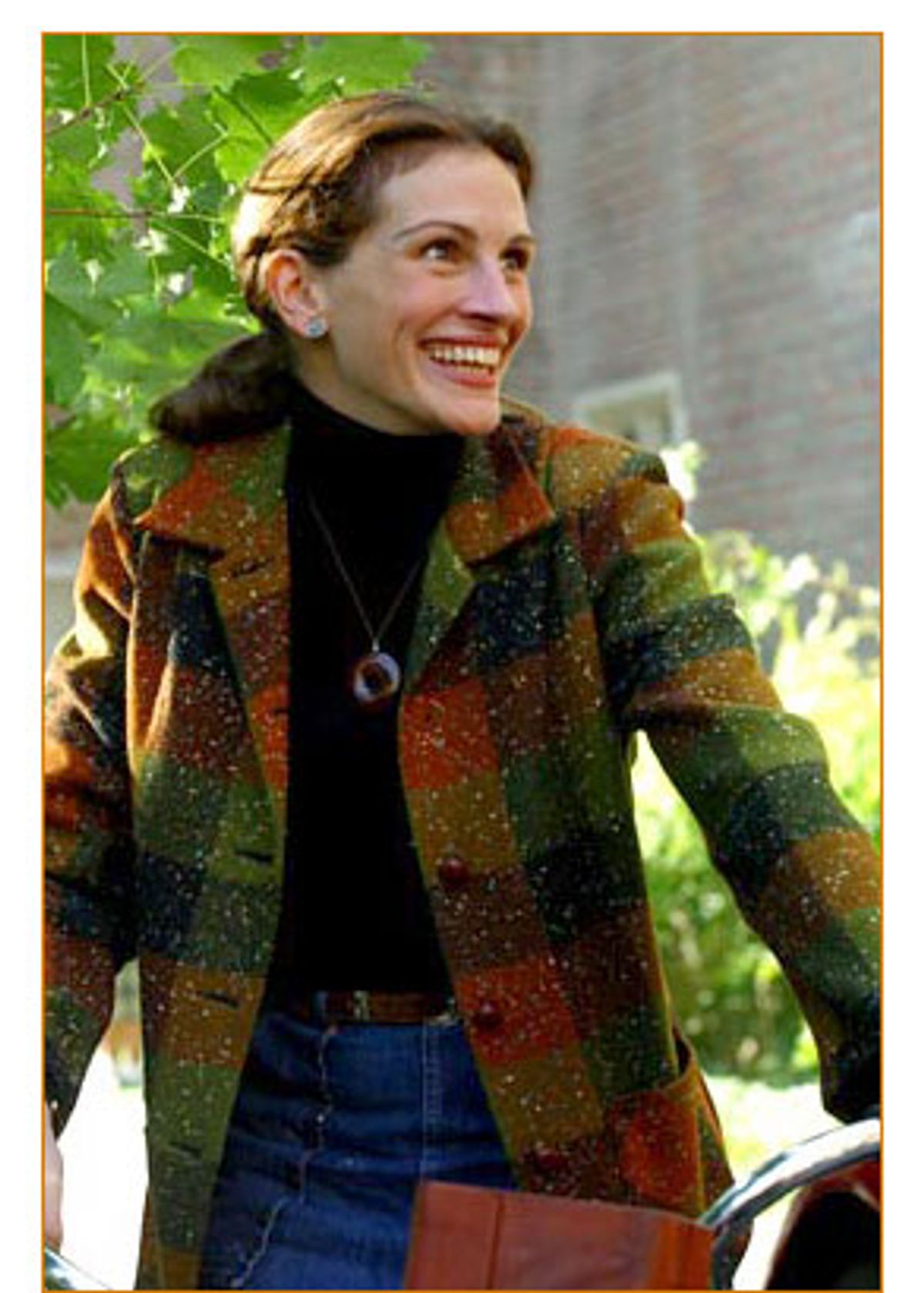

You don't even need to see "Mona Lisa Smile" to find out the answers to most of those questions, but the answers aren't the point: The getting-there is. Shot by Anastas Michos, the picture has a crisp, burnished sheen -- it looks like the New England of our dreams (which makes sense, since most of it wasn't shot in New England at all). And the costumes, by Michael Dennison, are fascinating in their detail (particularly the stylized Mexican silver jewelry he gives Roberts, which is exactly the sort of thing a West Coast bohemian of the 1950s would wear -- in our movie dreams, at least).

It's a good thing there's plenty to look at in "Mona Lisa Smile," since, despite the movie's roster of terrific actresses, the performances are disappointingly uneven: Dunst and Stiles are both too mannered and precise, even for the stiff, convention-bound characters they're playing. One wonderful actress, Juliet Stevenson, surfaces for a few scenes at the beginning only to disappear altogether, which is a bummer.

Marcia Gay Harden, as a Miss Lonelyhearts type who teaches deportment (she's also Katherine's landlady, welcoming the newcomer into her uproariously staid house of chintz), has some astonishing moments, but she's underserved by a badly written role. We're invited to laugh at the way, dressed in her starchily pressed circular skirts, she teaches her girls that their husbands' bosses will be scrutinizing them for their skill as hostesses. Then she's given a scene in which she tries to flirt, drunkenly and unsuccessfully, with an attractive bartender, humiliating herself and exposing the wounds beneath her polished exterior -- Harden is too subtle an actress for that kind of starkly cartoonish writing.

But Goodwin, as the boyfriendless, cello-playing misfit, is a delight to watch. She's so saucy and innocently sexy that you have no doubt she'll eventually win at love. (It's a measure of the movie's blindness that, with her alluringly rounded shape, Connie is treated as the "fat" girl, even though her figure was the body type that '50s men -- not to mention plenty of contemporary ones -- would be most likely to fall for.) And Maggie Gyllenhaal, as Giselle Levy -- the "fast" girl, and also the only one who happens to be Jewish -- is smashing. The movie feels truest, shoddy ideas and all, whenever she's on-screen.

In the midst of all Giselle's youthful mistakes (she's the girl who drinks too much and sleeps with her teachers), she's the most forceful character of the bunch, the one who trusts her inner compass. The movie makes the mistake of suggesting that she's headed for self-destruction simply because she likes sex, which is a hell of a message for a supposedly feminist movie. Even so, Gyllenhaal, with a mix of vulnerability and sensual confidence, is one of the few actresses here who succeed in playing a person and not a stereotype.

Which is not to say that the movie's stereotypes, particularly when they're played by Julia Roberts, aren't enjoyable to watch. I used to be almost consistently annoyed by Roberts; now, much of the time, I find myself caught in her snare. Her giant moon-crescent of a smile is like the corny coda at the end of "Take the A Train" -- you know it's going to show up sooner or later, it's familiar to the point of goofiness, but you have an affinity for it just the same. As Katherine, Roberts gets to do a bunch of things that make sense for her character and for the times (like wearing great modernist jewelry and introducing her conventional young kits to crazy artists like Jackson Pollock) and many, many things that don't. When she's looking for lodging at the beginning of the movie, she rejects one room because male visitors aren't allowed and goes off to find another; but when her West Coast boyfriend, played by the eminently likable John Slattery, shows up to visit her, she insists that men aren't allowed at this one, either.

"Mona Lisa Smile" throws in lots of curveballs like that, without ever really making sense of them. For example, Katherine needs to learn the lesson that, much as she wants the young women of Wellesley to be open to the types of freedom she enjoys, they're not all cut out for it. The movie wants to make sure we understand that being a stay-at-home mom and homemaker is a valid choice -- the problem is, it's exactly the wrong choice for the character who ends up making it. If "Mona Lisa Smile" is going to be so conventional that its characters must "learn lessons," the lessons should at least make sense.

The movie wants to have its bread buttered on both sides, and on the crustless edges too. And yet -- there's Roberts, standing in front of a class of perfectly coiffed ladies-in-training in her hand-knit cardigans and flat shoes (outfits in which she looks unaccountably glamorous), showing them slides of raw-meat paintings by Soutine. In an earlier scene, she's tried to show them some nice, basic cave drawings, only to learn that they already know about all that stuff -- they're such eager beavers that they've gone ahead and read everything on the syllabus ahead of time. She's dismayed and dispirited, but she comes back fighting, and the scene is gratifying. She shows the young women a photographic portrait of her mother and asks, "Is it art?" When they assure her it isn't, she comes back at them: "What if I told you it was taken by Ansel Adams?"

Katherine is teaching them not just to think for themselves, but also to see for themselves -- a subtle difference that the movie doesn't grasp so well as it moves along, with all its noisy pronouncements about the benefits (and drawbacks) of unconventional, modern lifestyles like the one Katherine has chosen.

But the sight of that Soutine slide, jumping up in front of these silly, self-important girls like a sexy demon from hell, is invigorating beyond belief. The painting, by 1953, is already more than two decades old, but it's news to them, and we feel their surprise like an electrical jolt. It's one of the moments in which "Mona Lisa Smile" works on us in spite of itself. We've been zapped not by the shock of the new, but by the shock of the old: The familiar moment when the sympathetic, outsider teacher stands up in front of her sassy pupils and teaches them a thing or two.

In terms of the gap between the movie it's trying to be and the movie it actually is, "Mona Lisa Smile" is in many ways indefensible. Yet for all its problems, it's satisfyingly movielike. The minutes drift by pleasurably and mindlessly. Its attempts to provoke thought are as ethereal as the smoke from a burned bra, but by the end there's no doubt you've just seen a movie. For the past two hours, you've been soaking in it.

Shares