The title “Millennium Mambo” suggests a dance along the edge. And “millennium” is always a word that invokes drama and the potential for tumultuous finality. There’s none of that sort of drama in Hou Hsiao Hsien’s 2001 film, only now being released in the United States. Instead Hou, the legendary Taiwanese director widely regarded by cinéastes as one of the greatest living filmmakers, though his films have received only sporadic release here, uses the title to evoke an existence of busy stasis, the indeterminate feeling of living on the cusp knowing that the future is likely to hold more of the same.

The film’s characters are all reaching the breaking point of lives spent in undifferentiated routine, but Hou’s quiet, seemingly undramatized style doesn’t suggest any looming cataclysm; there is no promise that anything either good or ill is in the cards. Hou’s heroine, Vicky (Shu Qi), narrates the film in the third person from the vantage point of 2011, 10 years after the events we see, and her remarks don’t tell us how — or even if — her life has changed.

I confess that my own experience with Hou’s films has been fragmentary. The few that I’ve seen have driven me to distraction. “Slow” should not automatically be a synonym for “boring,” but there’s no escaping the element of the boring in “Millennium Mambo.” I think, though, that “Millennium Mambo” is one of those works in which you have to surrender to the pace in order to get anything out of it. And though there are times when you think, for God’s sake, man, get on with it, I found the film hypnotic.

The combination that allows Hou to be a mesmerist here is the contemporary setting (though a contemporary setting didn’t much help Hou’s “Goodbye South Goodbye”), the pulse of the electronica score, the bleeding neon colors of Mark Lee Ping-bing’s cinematography, and the director’s apparent infatuation with his star, Shu Qi. The drama of “Millennium Mambo” lies not so much in what’s on-screen but in the tension between what we’re watching — the aimlessness of Vicky, her DJ boyfriend Hao-Hao (Chun-hao Tuan), and Jack (Jack Kao), the middle-aged gangster she’s drifting toward — and the unhurried precision of Hou’s direction. Ping-bing (who co-shot “In The Mood For Love” with Christopher Doyle), gives us slow pans that prowl around the apartments and nightclubs that Vicky and the two men inhabit. The sense is not so much that we are waiting for something to be revealed (at least not in the conventional dramatic sense) but that, as Gavin Smith wrote of the movie in Film Comment, Hou is “emphatically resist[ing] the accelerated pace of modern life [to] wrest accumulated meaning from seemingly inconsequential details.”

While watching “Millennium Mambo,” I thought often of Jean-Luc Godard’s “Masculine-Feminine.” Like Godard, Hou is trying to take the measure of youth at this moment in time. “Millennium Mambo” is in nowhere near the same league. It doesn’t have the grace or the depth. Hou may be smitten with Shu Qi, but he isn’t in love with her generation, the way Godard was in love with the ’60s generation, even when he was criticizing it.

Godard in his ’60s films was working to keep up with a culture that was changing at an inhuman speed. Ideas, aphorisms, allusions were tossed onto the screen often in a way that seemed oblique and half-formed. Capturing the moment before it passed (what Pauline Kael called Godard’s making documentaries of the future set in the present) was more important to Godard than presenting a “finished” work.

Hou, on the other hand, is such a formalized director that you can’t imagine him putting anything on the screen that hasn’t been rigorously planned. There’s no urgency in his filmmaking. Godard was passionately caught up in the decade he was recording. His movies came at you like reports from the front of a battle whose sides and theaters of combat were always in flux. Hou, on the other hand, is making an elegy. As Gavin Smith suggests, he is, at some level, resisting contemporary culture, though “Millennium Mambo” doesn’t feel cut off from that culture or superior to it.

The key to the movie seems to be in the nature of Hou’s resistance. There was something new in Godard’s insistence that high art and pop art, philosophy and politics and pop music and movies all inhabited the same world. In a media-saturated culture, that’s no longer a new idea. The irony of those juxtapositions is no longer surprising or fresh. A filmmaker who tries to keep pace with today’s culture runs the risk of merely imitating it with quick cuts and flashy surfaces, of turning out merely another shiny artifact for the deconstructed cultural junk heap.

If Vicky and Hao-Hao come across as self-absorbed, it’s because the social context they inhabit — clubbing as temporary respite from their dead-end lives — doesn’t seem to allow for any other possibility. Vicky lives on the savings she has put aside (several times she says that when her money runs out, she will leave Hao-Hao), Hao-Hao on what he can steal. Neither of them has any ambition, any hopes. For them the future barely exists beyond the next drink, the next cigarette, which may be why the coming millennium stirs them so little. The apartment they live in is shared only in the sense of two people sharing a mutual annoyance. They’re in the same room but in their own bubbles. Their nights out in the clubs have a frantic quality, allowing them, for a time, to escape their tiny apartment, but never quite to escape their ennui. The details of their lives — Vicky cleaning up the food and cans Hao-Hao leaves scattered around the apartment, his preoccupation with practicing his DJ skills (which never result in a gig), the desire she transmits to be left alone like some club-kid Garbo — come to feel like holding patterns, small bulwarks against an enveloping emptiness.

However, once you get into the groove of the film’s sometimes maddening slowness, you feel as if your senses have been sharpened. Hou places you at a remove from the pace of his characters’ lives to allow you to observe them as closely as you can. But Hou gets himself into another kind of bind. It’s one thing to resist the rapacious speed of a cannibal culture, but because the vapidness of their existence is really all there is to see of these characters, “Millennium Mambo” is, in some ways, another stylish artifact. There are no hidden depths revealed in Hou’s molasses-dripping sense of time. If you put “Millennium Mambo” next to Wong Kar-Wai’s “Days of Being Wild,” about Hong Kong youth in the early ’60s, in which the slow pace did result in revelation, “Millennium Mambo” might feel very slight.

Still, what Hou shows us has the recognizable contours of life, of people trapped in lives they have no idea how to — and maybe not even the will to — change. The shallowness of the characters doesn’t cause you to dismiss “Millennium Mambo,” because Hou never makes us feel that we are watching mere posing. Vicky may be shallow, but she’s not dead. “Millennium Mambo” never falls into the chic anomie of Michelangelo Antonioni’s fetishizations of the rich living dead. You never feel as if Hou is secretly coveting the emptiness he’s showing us. There is compassion in his treatment of Vicky, an empathy for someone who feels and suffers but doesn’t have the experience or the resources to get out of her predicament. And the combination of the thick sensuality of Mark Lee Ping-bing’s cinematography and the gradual fascination that Hou’s measured rhythms exert keep you watching.

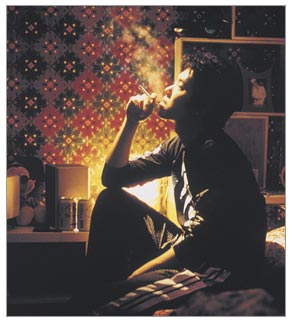

Shu Qi also keeps you watching. A Hong Kong starlet who got her start in soft porn and graduated to action roles in pictures like Corey Yuen’s “The Transporter” and “So Close,” Shu Qi is a gorgeous camera subject. Her otherwise delicate features are given a ripeness by her prominent nose and over-generous mouth. There’s no point in proclaiming her a great actress, but for the role of Vicky, she doesn’t need to be. (Some of the most memorable women in Godard’s movies weren’t great actresses, either.) What she does need to do is to exist comfortably in front of the camera. She moves through “Millennium Mambo” like someone used to being watched, whether she’s lighting a cigarette or rebuffing Hao-Hao’s adolescent sexual overtures. The movie would be simply unthinkable without her star presence, and Hou’s willingness to respond to her, to let the camera feast on her, to allow his observation to take on the qualities of fetishization, give the movie a glamour that otherwise would make it punishingly slow and blank.

What’s more, Shu has a talent for petulant suffering. Even when Vicky is reduced to lap-dancing in some sleazy club she seems resigned to her fate. And with Jack, who becomes her protector more than her lover, and who possesses the experience and common sense that she lacks (he’s a delicate sort of tough guy), she seems content to fall into the role of cared-for pet rather than taking the chance he offers her to turn her life around. But the fact that Vicky narrates in the third person, as if her earlier self were a character she can speak about with some distance, suggests that her future holds a break with this past. Her present state is as transitory as the outline of her face that she presses into a snowbank. The distance between the glimmers of dissatisfaction she shows and the ruefulness we hear in her “older” voice work to give us sympathy for the characters. And so do the privileges of beauty. Shu Qi is simply one of those luscious creatures that we go to the movies to watch, and if that sounds shallow, it’s no less a fact of our moviegoing. That Hou is open to her glamour does much to make “Millennium Mambo” seem less rarefied than it could.

And Shu Qi’s glamour isn’t the only link here to the traditional pleasure of movies. “Millennium Mambo” ends in flashback, as Vicky and some friends wander the snowy nighttime streets of Yurabi, Japan. They are walking along Cinema Street, so named because huge movie posters adorn the top of each building, for everything from French policiers to the Japanese Tora-san series. Along with the melancholy of ending the film by showing us one of his heroine’s rare moments of simple happiness, Hou evokes a longing in this scene for the very idea of movies, and perhaps for the idea of movies he loves but knows he can’t make.