“Kiss me Hardy.” — Dying words of Adm. Lord Nelson, at the battle of Trafalgar, 1805

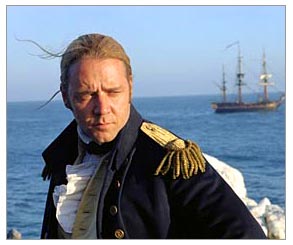

In Peter Weir’s “Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World,” Russell Crowe plays fictional British Royal Navy officer Jack Aubrey, a ship’s captain beloved by his men for his good judgment, fairness, courage and affability. In one of the movie’s most eloquent and haunting scenes, a young sailor is tossed overboard in a storm when the mast he has climbed suddenly breaks. He cries for help as he thrashes amid the waves, clinging to bits of broken wood still connected to the ship by tangled rigging. Aubrey’s first thought is to save him, until he realizes that the wreckage the man is clinging to is acting as a sea anchor, crippling the ship and dooming them all.

Aubrey makes his decision in a flicker of a second, but with complete knowledge that not all seconds are created equal: This one in particular is a significantly swollen measure of time, a voluminous and weighty tick of the clock whose repercussions are likely to stick with him for life. He calls for a few axes and hands them to two of his crew members, one of whom, the carpenter’s mate, also happens to be the drowning man’s best friend. The understanding is that they need to sever the rigging to free the vessel, which will also leave the man adrift and abandoned in the sea.

But Aubrey doesn’t just hand the tools to his men so he can watch them do the dirty work. He takes an axe in hand himself and joins them in hacking away at the ropes — an almost literal way of putting the man’s blood on his hands. The ship lurches free and moves forward, leaving the doomed man further and further behind until he disappears. Yet there’s little doubt that the more crushing loneliness rests with the man who made the decision.

“Master and Commander” is a movie made in 2003 and set in 1805 — in other words, it’s a picture about an era that we can easily accept as romantic and heroic, made in an era that seems anything but. Most modern adults are consumed with making a living or raising kids or both, and, at least in the conventional sense, there’s nothing remotely heroic about changing diapers or writing software code.

Which may be precisely why images of heroism in the movies refuse to die, and also why our own leaders curry favor with us by grabbing at the trappings of heroism, donning flight suits as if they were superhero Halloween costumes, and questioning one another’s military heroics. Four-star Gen. Wesley Clark tried to pull rank over the highly decorated Sen. John Kerry (“… he’s a lieutenant and I’m a general”) while Democrats have been quick to try and contrast Kerry’s honored record with the president’s questionable one. As much as we may think we’re too sophisticated to believe in anything as corny as old-fashioned heroism, few of us are beyond its grasp. In the past year, besides Crowe in “Master and Commander,” we’ve seen Tom Cruise cozying up to the way of the sword in “The Last Samurai.” There wasn’t much authority in Cruise’s pinched, tinny battle cry, but audiences clearly responded to his Nathan Algren’s New Agey exploration of the meaning of duty and honor in battle. And you don’t need to be bonked on the head with an old Joseph Campbell paperback to recognize that, in “Lord of the Rings: Return of the King,” the characters of Aragorn and Eowyn (played by Viggo Mortensen and Miranda Otto, respectively) reach deep into our archetypal subconscious to pull up the quintessential definition of the word “hero.”

But even if we can’t help responding to such brave nobility in movies, those of us who identify ourselves as liberals can feel a little ambivalent about the concept of heroism. Unless we’re talking about everyday heroes, like firefighters — who, most of us would agree, represent heroism in its purest form — the mere concept is suspect. After all, only blowhard Republicans use high-handed phrases like “leadership qualities” and “question of character,” terms that go hand-in-hand with the concept of heroism. Good liberals chafe against that sort of language, even if not against its true meaning: The point is that we’re all too aware of how the terms of heroism have been hijacked and harnessed into the service of conservatism and conformity. Politically speaking, heroism has become conflated with the idea that “might makes right.” It’s much more democratic, in theory at least, to walk softly and carry a big stick, particularly one that you have little intention of using.

But true heroism — the sort that Jack Aubrey represents, as opposed to the kind that’s designed with photo-ops in mind — has very little to do with kicking ass. We are, and will be for the foreseeable future, a nation at war. Are we looking, perhaps subconsciously, for some element of heroic leadership to guide us safely out of the mess we’re in? Our current commander in chief (the title itself has an innately heroic quality, even when the man holding it does not) clearly has some kind of hero complex. And while one of his would-be challengers, Clark, stressed his military experience, he seemed to purposely avoid playing the “hero” card, adhering to the code of discretion common among military men.

Even so, it has been suggested that Clark had a particularly weak following among women primary voters, perhaps because they were put off by the fact that he’s been part of what is so quaintly called, even today, the “war machine.” It could be that, while we harbor some archetypal craving for heroism in the abstract, we’re a lot less comfortable with some of the elements of real-life heroism: In other words, the fact that it sometimes means getting one’s hands not just dirty, but bloody.

But then, why do we think of heroism as being inherently male in the first place? Is it possible that heroism is so delicate and finely calibrated a quality that it’s almost a feminine, or at least a gender-neutral, one — one that has more to do with empathy and fortitude than with brute strength or unchecked egoism? Could it be one of those unidentifiable inner fires that burns brightest in the female side of every man, and the masculine side of every woman? At the beginning of the 21st century, we think we have an idea that heroism must conform to a hyper-macho ideal. So how do we explain why, on his deathbed after being wounded in battle, one of the greatest real-life heroes of all time, Adm. Lord Nelson, asked another man to kiss him?

In Great Britain, at least, Horatio Nelson is the hero’s hero. He was a brilliant and aggressive naval commander who gave his life for his country: He was shot through the spine with a musket ball at the battle of Trafalgar, as his ship, HMS Victory, fended off combined French and Spanish forces, thus skewering Napoleon’s attempts to invade England.

But you can’t read a single book about Nelson, or look at any of the many Web sites lovingly tended by those who keep his memory alive, without recognizing that his brave acts are only part of his legend: Most Nelson buffs would probably tell you that what the man did is inseparable from who he was. In other words, he’s as much beloved for his character as for his actions.

Nelson wasn’t standard-issue hero material. At 5 foot 6, he wasn’t particularly tall, even by the standards of the day. His health was at times fragile. He could be vain, and he craved attention to an unbecoming degree. He conducted a passionate and highly public love affair with the married Lady Emma Hamilton, who bore him a child; he treated his own wife, Fanny, shabbily. But Nelson was beloved and admired by his contemporaries and by those who served under him. His leadership qualities were unparalleled: His men would do anything for him. Sea-toughened sailors, on hearing of his death, wept openly. Apparently, kindness was as much a part of his makeup as courage. At the very least, he knew how to relate to people.

In his recently published, rousingly readable biography, “Nelson: Love and Fame,” Edgar Vincent explains the man’s appeal this way:

“His myth endures because the emotions of victory were intensified by the poignancy of his death in the hour of victory, because the feelings he evoked among those he led were so tender, because of his love for one of the most celebrated beauties of the age, and because what he had accomplished was indisputable and of infinite value to the morale and self-identity of a nation under present threat of invasion. Nelson became the most tangible hero in England’s history. There is no other great leader whose funeral has caused a remotely comparable outpouring of grief. His column in Trafalgar Square soars infinitely higher than the statue or monument of any other individual in Britain’s history.”

That’s as good a thumbnail sketch as any, but in his introduction to the book, Vincent also explains, “Not surprisingly there has from the beginning been a remarkable merging of two Nelsons, the person and the icon.” And he reveals that after eight years of researching the book, “I have not ended up with an icon or the Nelson I began with” — a way of saying that even the most staunchly heroic of heroes are complex and slippery when we start to look at them as human beings.

And at the core of heroism, of course, lies human frailty — in other words, the risk of death. Nelson died for his God and his country; pretty noble, if you go for that kind of stuff. But even if you don’t, the death of Nelson is heartbreaking by any standard, simply because it underscores the vulnerability of even the bravest warrior. Vincent recounts how Nelson lay bleeding in the bowels of his ship for several hours, his physician helpless to save him. His first thoughts were for his mistress and the couple’s young daughter, Horatia — it was of the utmost importance that they be looked after. Over the next few hours, he drifted in and out of consciousness. He asked for his flag captain, (Sir) Thomas Masterman Hardy. “Don’t throw me overboard Hardy,” he implored, as wrenching a plea as any hero has ever made. As Nelson’s last moments approached, he seems to have attempted a confession of sorts: “Doctor, I have not been a great sinner” — something of a mischievous understatement for a dying adulterer. (Vincent writes, “Even now he was not going to face the fact that he had broken at least three of the Ten Commandments.”)

Nelson’s most famous words weren’t actually his very last. But as dying words go, “Kiss me Hardy” nonetheless have to be among the three greatest. The loyal Hardy, clearly moved by the request, complied, kissing Nelson on the forehead. Then, impulsively, he kissed Nelson again of his own accord. Nelson, flickering back into consciousness, asked, “Who is that?” Hardy replied, “It is Hardy.” Nelson responded, “Bless you, Hardy.”

There are many ways to read the death scene (and, as Vincent points out, “In it there is something for all of us.”). But there’s no doubt that in his last hours, Nelson craved the human touch. Naturally, he’d asked Hardy how the battle was going; he wanted to make sure his side was winning (it was). But at his end, one of the most courageous men of all time — one whose actions had changed the course of history — was anything but hard. What he craved at the last was tenderness, and he wasn’t afraid to admit it.

Cut to 2003 and the vision, beamed ’round the world on television, of George W. Bush landing on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln in that flight suit. To borrow the parlance of fashion magazines, Nelson is “out”; Bush is “in.” If this is what we call heroism these days, it’s little wonder we have no use for it.

We do have an instinct for sniffing out true heroism when it happens. No one would deny that the firefighters who responded so valiantly on 9/11 are heroes. Heck, even the 9/11 search-and-rescue dogs qualify as heroes. And we’re all open to the idea of nurses and teachers and volunteer workers as heroes, considering that they do the tough jobs many of us just couldn’t handle.

But we don’t like heroism as a political sales tactic — or at least, there’s a part of us that knows we shouldn’t. Besides that, there’s no way of knowing if brave military men — the sort who are most likely to be heroes of one kind or another — necessarily make the best leaders for a country.

But there is something to be said for gauging a man’s attitude to the notion of heroism. In his Esquire profile of Wesley Clark last August, before Clark had declared his candidacy, Tom Junod made a clear demarcation between the attitudes of the current president and those of one guy who’s hoping to take his place. “Accountability is the value that he hopes to export from military to civilian life,” Junod writes of Clark, “the value that informs even his most fledgling attempt to formulate a platform, the value by which he hopes America’s education system will be rebuilt, with teaching professionalized in the new century the same way soldiering was at the end of the last. And it is the value that makes whatever policy disagreements he has with President Bush seem strangely personal, for it is the value that distinguishes a warrior from, well, a warrior president.”

“Accountability” is a word that Jack Aubrey, with his axe, would understand intuitively. Junod goes on to provide even more telling details about Clark’s attitude toward bravery in wartime — or, for that matter, any other time. In August 1995, Clark went to Bosnia as part of a negotiating team put together by Ambassador Richard Holbrooke in an attempt to end the still-raging civil war. The team had to travel to Sarajevo, and Clark asked Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic for protection on a road that was controlled by Bosnian Serbs. Milosevic refused. The team split into two groups: Clark and Holbrooke traveled in a Humvee, the others in an armored personnel carrier.

In his book “Waging Modern War: Bosnia, Kosovo, and the Future of Combat,” Clark explains that the personnel carrier “broke through the shoulder of the road and tumbled several hundred meters down a steep hillside.” But Junod points out that Holbrooke, in his book “To End a War,” describes the way “Clark grabbed a rope, anchored it to a tree stump, and rappelled down the mountainside after [the APC], despite the gunfire that the explosion of the APC set off, despite the warnings that the mountainside was heavily mined, despite the rain and the mud, and despite Holbrooke yelling that he couldn’t go.” The APC, Junod learns after probing the general about the episode, “had turned into a kiln,” and “Clark stayed with it and aided in the extraction of the bodies.”

That story never showed up as part of Clark’s campaign. But then, maybe that underscores the essential distinction between heroic behavior and heroic character. Similarly, as far as campaigning goes, Sen. John Kerry has used his own experience as a Navy lieutenant in Vietnam in only relatively vague terms. But despite the fact that he earned a Silver Star, a Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts during his two tours of duty in Vietnam, he has had to answer charges from his opponents about the sincerity of his convictions regarding Vietnam. Upon his return from duty, in 1969, Kerry became a vocal member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, although it’s also worth noting that, as reported last June in a four-piece Boston Globe profile of Kerry written by Michael Kranish, that he had spoken out against the war in a speech he delivered at his graduation from Yale in 1966, even though he was already enlisted and on his way overseas. The point isn’t that Kerry waffled in his convictions: Doesn’t it make sense that men who have actually seen combat — as opposed to the legions of white-collar politicians who found tidy and ingenious ways to avoid it — should be allowed conflicted feelings about the morality of any wartime enterprise? Although many of the men who served under Kerry have spoken highly of his bravery and leadership qualities, I’d argue that his real heroism kicked in when he returned home and began questioning his country’s motives, after he had risked his own life to serve that country.

Obviously, the concept of heroism is still a hot button, even though there are plenty of people who haven’t bothered to think about what it really means. Can the notion of heroism — that is, heroism as a mysterious amalgam of character, bravery and discretion — be reclaimed? Forget thinking about heroism in military terms: Do we even have to assign it a chromosome as well? In “Return of the King,” Viggo Mortensen’s Aragorn is masculine, all right. But even then, he cuts a figure that’s all about the poetry of masculinity. His counterpart, Miranda Otto’s Eowyn, has much less screen time, but she’s an even more intriguing mix of character traits: She’s a pre-Raphaelite warrior whose tenaciousness is something like the fierce side of motherhood.

And then there’s Jack Aubrey, cutting loose one of his men, a man who looks to be in his late teens — in other words, a man who’s not much older than a boy. In “Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World,” as in the Patrick O’Brian novels on which it’s based, Aubrey looks up to Lord Nelson, and tells a story about how the admiral, walking on deck one bitterly cold night, refused the offer of a cloak: His love of king and country kept him warm, he said.

Aubrey himself recognizes the cornball quotient of the anecdote. And yet he treasures it, probably because when you’re in charge of making decisions regarding the life and death of others, if not yourself, it helps to have a more noble human creature than yourself to believe in. As for Nelson, he died in a pool of his own blood, after giving up all he had for God and country. Even so, in the end, it all fell down to a kiss. In that one voluminous, eternally hanging moment, his motto might have been, Make love, not war.