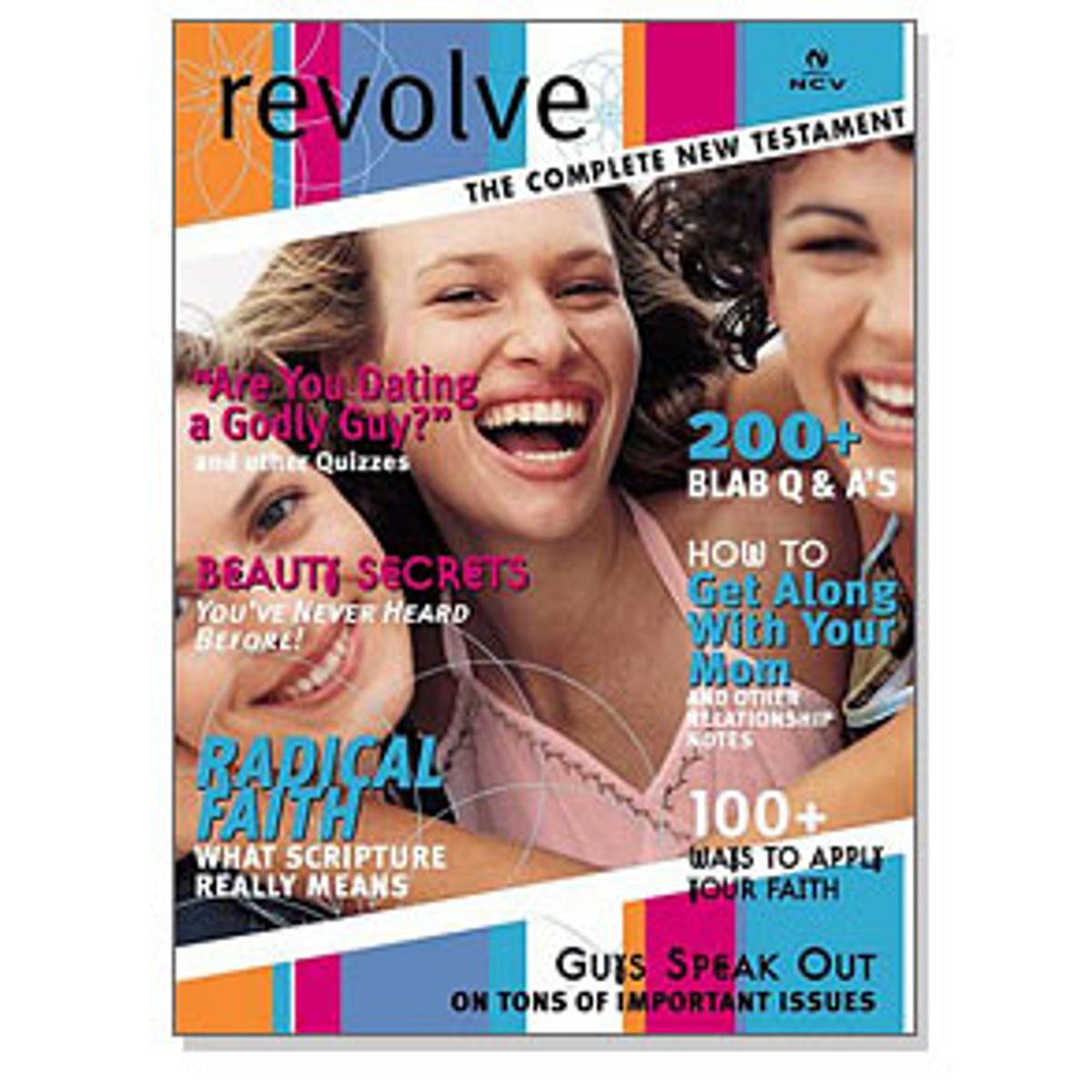

What would Jesus do about clogged pores? It's a topic on which the Bible is mute. Unless the Bible being consulted is Revolve, which dresses up the New Testament to look and read exactly like a teen magazine -- complete with cover lines that promise much more than the Good News inside. "Guys Speak Out on Tons of Important Issues," declares one, hinting that the guys holding forth aren't Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Others offer "100+ Ways to Apply Your Faith" and "Beauty Secrets You've Never Heard Before!"

That's for sure. "As you apply your sunscreen," one reads, "use that time to talk to God. Tell him how grateful you are for how he made you. Soon, you'll be so used to talking to him, it might become as regular and intimate as shrinking your pores." And what exactly are those aforementioned guys speaking out on? Comportment. They like girls who dress conservatively, wear as little makeup as possible, and don't overreact if they don't notice a new haircut. Thinking of asking a guy out? Revolve girls don't. "Sorry," they're told. "God made guys to be the leaders. That means that they lead in relationships. They tell you they like you." If you need distraction from that total bummer, there are charts ranking the "top ten random things" you can do to make a difference in your community or bond with your dad. Or calendar pages that designate celebrity birthdays as occasions to Pray for a Person of Influence. (Kelly Osbourne and Anna Nicole Smith, junior varsity prayer warriors have got your back.) As well as quizzes that pose such questions as "Are You Crushing Too Hard?" and "Are You a Good Daughter?"

Revolve was published in July after Thomas Nelson, the largest English-language Christian publisher, noticed that, on one of the company's Web sites, teens were complaining that the Bible was too intimidating. Knowing that teen girls were hooked on magazines such as Teen People, CosmoGirl and Seventeen, the publisher decided to wrap an accessible translation of the New Testament in the trappings of an irresistible medium. "Reading the Bible is not as scary as it seems," Revolve readers are assured. "The Bible is God's love letter to us and an instruction manual and answer book for life, so we should read it with the same passion we'd have when we read a letter from our biggest crush." The $14.99 love letter is doing big business: Since Revolve hit shelves this summer, it's almost sold out of its initial print run of 40,000, and Thomas Nelson is about to print 110,000 more. The company is planning to ship new editions of Revolve every 12 to 18 months to update celebrity names and information on featured charities. A version for teen boys -- as yet untitled -- is also in the works.

Laurie Whaley, the 28-year-old Thomas Nelson brand manager who helped create Revolve, says that she's gotten hundreds of e-mails from girls around the country gushing about the user-friendly Bible. "Just wanted to share what my girls thought of your new product," one California girl wrote. "Exact words were 'TIGHT!'" Some might sigh in dismay at the dropping of articles and the overenthusiastic deployment of slang to review God's word. Whaley, however, is psyched. Her mission -- to capture the attention of girls between the ages of 12 and 15 -- most of whom come from Christian homes and are looking to understand their faith -- has been accomplished.

Marsha Yaunches is a 17-year-old from a suburb in southern New Jersey who was introduced to Revolve by a youth pastor at her evangelical church. Though the beauty tips don't thrill her -- she's "one of those people who wears sweatpants everyday to school" -- she declares the book "really cool" because "it brings everything down to a girl's level." Meaning that it's talking to her about her beliefs without patronizing her. "It's not, 'This is what so-and-so thinks,'" she says, doing an impression of an out-of-touch, possibly megalomaniacal authority figure. Amy McTeak, 16, from a suburb of Nashville, loves Revolve's quizzes because they help her to examine, among other things, her dating standards. Amy, who says she will occasionally pick up a secular girls' magazine if "Hilary Duff or Mary-Kate and Ashley are on the cover," doesn't see anything wrong with sprinkling some sugar on top of Scripture. "Back in the olden days, teens didn't have so much to distract them from reading the Bible," she says. "If this makes it fun, then it's a good idea, as long as it's taking God seriously, which this does." Even Emily Ross, a 15-year-old Manhattanite who is a lector at her Episcopalian church, and who has definite opinions on hermeneutics, is enthralled. "You can't always take the Bible literally," she says. "It was written in a different time period." But she still exclaims "Awesome!" within seconds of being shown a copy of Revolve, citing the "basic, common" language and the "Blab" columns, which give counsel on everything from pot smoking to tattoo wearing to the possibility of alien life.

Like the other Christian girls interviewed for this article, Emily is a regular churchgoer and Bible reader and does not relate to Seventeen and its sisters. "I'm not going to deny that I think about makeup and boys, which is what they're always talking about in those magazines, but my life is more than that," she says. Marsha agrees: "Most of the advice those magazines give is all nonsense. Some of it's legit, but 'hot sex tips'? I just don't care about that." Revolve appeals to these admittedly conservative teens because it acknowledges that they have inner lives and self-respect -- aspects of their character that they feel are not discussed in mainstream teen magazines.

It's not just Revolve that's affirming teenage girls' spirituality. Marsha and Amy are also avid readers of Brio, a monthly magazine that's been published by the conservative Christian organization Focus on the Family since 1990. As with Revolve, the aim is to make you pretty on the inside through frequent applications of the Word. Brio, which has a circulation of 160,000, delves into fashion (the spreads may have a Sunday circular aesthetic but feature labels found at Urban Outfitters) and music (Evanescence gets chastised for writing songs in which "sleep, daydreams and death are the best means of escape"). And last year the vocal quartet Point of Grace launched their Girls of Grace conferences -- think Promise Keepers with makeovers, designed expressly for the Lizzie McGuire set. The consistently sold-out events, which have been held in churches all over the country, have drawn 40,000 teens to date.

Whaley -- who says Revolve's title refers to a "twist on tradition" -- admits she can understand how using facials as a metaphor for the cleansing power of God's love could be considered silly. "Some of the tips, I grant you, are a little cheesier than others," she says. "The men in my office just don't get the one about foundation," she says, referring to this nugget: "You need a good, balanced foundation for the rest of your makeup, kinda how like Jesus is the strong foundation in our lives." But she set them straight. "I told them, 'Well, you're not going to get it, because you don't put foundation on every morning.'" Whaley doesn't think that discussing makeup and boys contradicts or cheapens the text it surrounds. "If you look at the New Testament and the life of Christ, he was coming to people where they were. He wasn't high and mighty. Jesus himself was a part of culture, and he understood using culture to communicate his message. We're just living out the New Testament. We've done nothing to change the message -- all we've done is change the packaging."

Those who haven't been raised in evangelical churches, which hold fast to Paul's command for wives to submit to their husbands, might take issue with the Bible's brand of gender politics. "We're not talking about for the rest of your life," says the Nashville-raised Whaley, a third-generation pastor's kid, of Revolve's no-calling-boys rule. "We're talking about 12- to 15-year-old girls, and what we're saying is 'Hey look, your minds are really young and formative. Let's guard them.'" Parents of boys whose houses had been firebombed by phone calls from overzealous girls have called Revolve to thank them for recommending caution, Whaley says. And she has yet to receive a letter from a teenage girl writing in protest -- in fact, she's mainly just been catching flak from incredulous media professionals. "Often people will try to find anything to pick on -- anything that goes contrary to what could be equality," she says. "But that's not what we mean to do at all." (Thomas Nelson is, however, taking out the sentence about God designating guys as leaders, because "it's been misinterpreted," says Whaley.)

Is it merely a coincidence, then, that Thomas Nelson published only a version of the New Testament, conveniently sidestepping all those strong Old Testament women like Ruth and Esther? Whaley promises an Old Testament version soon; she says the only reason they launched Revolve with just one half of the Bible was to avoid a product that "was the size of the Sears Roebuck catalog."

Brandon Holley, editor in chief of ElleGirl, says that though she finds the cheerful hawking of belief more than a bit creepy, Revolve's packaging -- and its reassuring approach -- is right in line with how you'd market a secular teen magazine for that age group. "It's very 'I'm your best friend,' very hand-holding. So if the publishers are going for a 12-to-15 age range, that tone is right. Girls at that age want to be comforted. They don't want a challenge."

Some worry that Revolve may be too comforting and feel that it's risky to make the Bible over in our image -- a trend that's grown over last decade or so. Publishers want to keep attracting buyers for a very old product; so niche-marketed, value-added Bibles padded with devotional readings and other informational marginalia have been proliferating like Snapple flavors. If you are a father, a leader, a woman of color, a sports nut, or a lover of the painter Thomas Kinkade, there's a Bible for you.

Paul Raushenbush, an associate dean of religious life at Princeton University who writes an advice column for teens on Beliefnet, believes, like Whaley, in reaching people "where they are," but he worries that the packaging may undermine the strong truths of the Bible. "I can't imagine another faith that would do this to its sacred text," he says. "You would never see this in Islam, which views the Koran as completely sacred. You do want people to be comfortable with the Bible, but it's not the same as Teen People. It takes study. It takes diligence. I'm worried that kids are going to think, 'I get it. The Bible is all about me and my life in middle school.'" But Raushenbush, who's writing a book of his own on teens and spirituality, admits that part of him finds Revolve kind of cool. "It's too easy to bash people's efforts. People are feeling so lonely, without a sense of grounding, and if this would help them at all, then great."

It is kind of cool -- in the sense that it's refreshing to think that Revolve may be providing teen girls some sort of alternative to Britney Spears. But then again Revolve might just be a symptom of the culture that gave birth to the pop starlet. Perhaps the teen Bible is a pure product of America gone crazy, to borrow a line from William Carlos Williams -- the result of a union between religion and capitalism. Beginning with the early 19th century, our brand of Christianity has always been marked by a desire to serve both God and mammon, says Steven Prothero, an associate professor of religion at Boston University and the author of the upcoming book "American Jesus." "Nobody else is as successful as American Christians are in making Christians," he says. "And nobody else stoops to such lows in doing so."

Prothero says that this isn't the first time Christian publishers have sold girls out on the way to a marketing revolution. "There was real resistance initially to adding anything to the Bible," he says. "But it began in the 1800s with illustrated editions that featured pictures of female characters, and this was thought to be a way to sell the Bible to women -- as if men could read it just for the text, but women would need some nice pretty pictures. Items like this were initially controversial, but they eventually sold more than regular Bibles."

Raushenbush thinks that since Revolve is a highly irregular Bible, it shouldn't be sold as one. "It should be viewed as an interpretation," he says. Perhaps then it should be marketed as a tool for discussion about the Bible's teachings, and should be labeled as such, so kids don't mistake Jesus as the author of dictums on, say, who should call whom.

Revolve has been serving just that purpose for Liz Powell, the director of the high school girls' ministry at Fellowship Alliance Chapel in Medford, N.J., which Marsha attends. Powell loves Revolve because she's never before seen girls, usually too overscheduled to make time to read the Bible outside church, so captivated by it. "The girls are having as much fun with the quizzes and columns as they do with the Teen People and CosmoGirls they bring on the bus for youth group trips. It's a format that encourages them to look at very topical things from God's perspective."

Powell tells a story about how the book caused a heated debate about, of course, which gender was biblically mandated to pick up the phone. The upstanding young men in her youth group said if the girls didn't, "they were never gonna get a date." But the girls said they preferred being pursued. One of them is Marsha, who when asked, looks up the verse from Paul's first letter to Timothy that supports her stance: "A woman should learn in quietness and full submission. I do not permit a woman to teach or to have authority over a man; she must be silent." Does she really believe that? Marsha pauses, her voice full of bravado and query -- a mix of notes that wouldn't be easily quantified in a focus group or by a pie chart. "To an extent," she says. "I mean, not if men are wrong and we're right -- which we are most of the time."

Shares