In August 2002, seven months before U.S. missiles began ripping into the Iraqi capital, a senior British official close to the Bush administration told Newsweek: "Everyone wants to go to Baghdad. Real men want to go to Tehran."

The quote ricocheted across the media, leaving opponents of the war convinced of the administration's wider designs in the Mideast. But those provocative words may have been less a burst of broad war-on-terror bluster than a more focused alarm over the spread of nuclear weapons: By some accounts Iran could now be less than a year from building them.

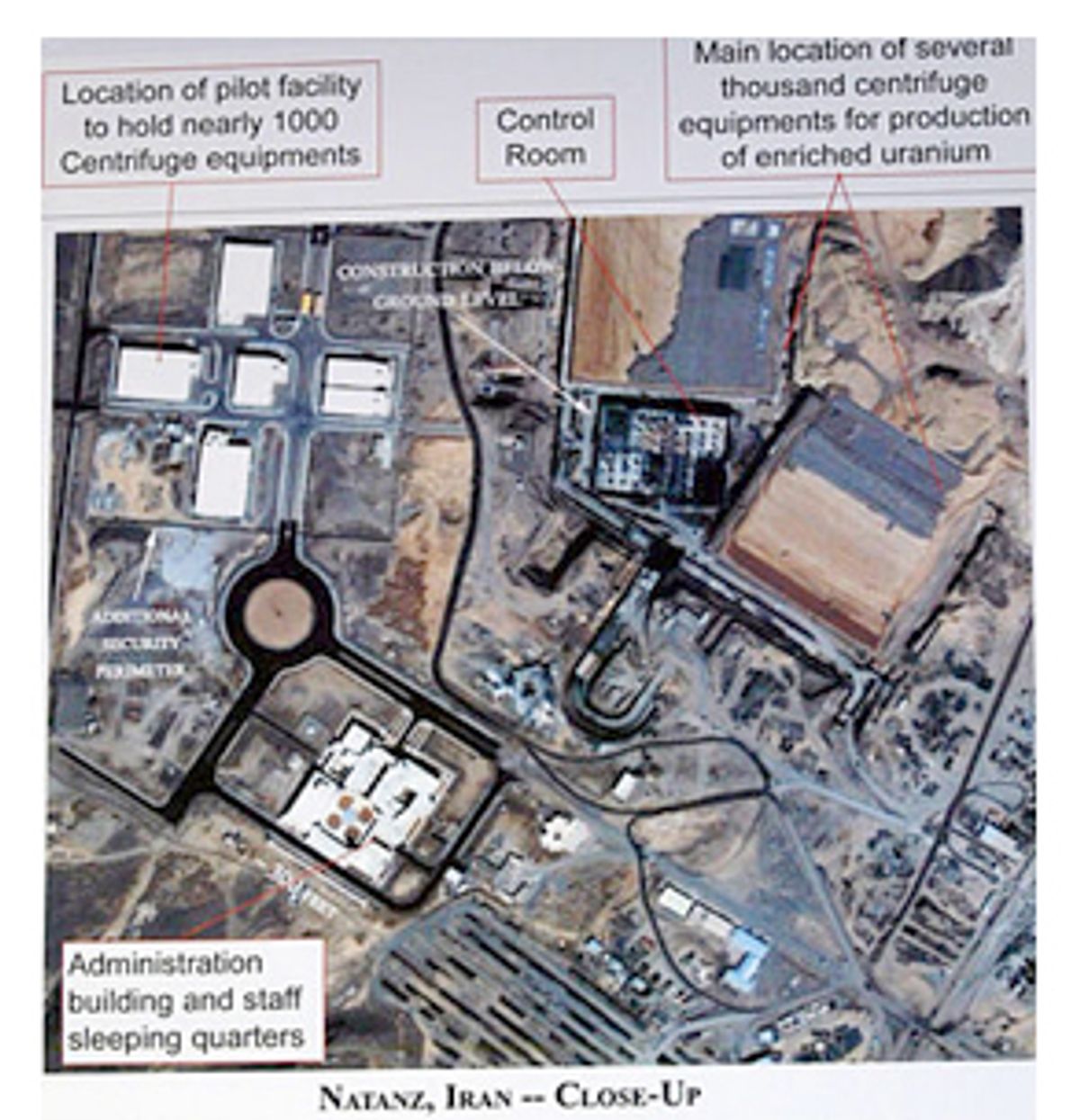

"It's undeniably true they're closer to nuclear weapons than we thought," says Flynt Leverett, a former National Security Council advisor now at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy in Washington. Leverett believes Iran is closer to two years away from nuclear capability, but he also points to last year's whistle-blowing by an Iranian dissident group -- around the time of the British official's statement -- as another alarming example of a familiar pattern: a failure of U.S. intelligence. "What's so disturbing was that until the National Council of Resistance of Iran stood up in Washington last August with photographs of facilities at Natanz and Arak, we didn't have a clue they existed," he says.

Recent inspections of those sites, combined with concerns about the Russian-built nuclear reactor in progress at Bushehr, exposed solid evidence that Iran sits on the cusp of weapons production. On Monday, Tehran confirmed successful testing of its Shahab-3 midrange missile, capable of striking anywhere in Israel. And in the wake of violent street protests in June, the mullahs timed a new invitation to international arms inspectors precisely for the July 9 anniversary of a bloody 1999 student uprising.

But even as the mullahs edge toward a nuclear capacity that could provoke American or Israeli retaliation, the Bush administration's Iran policy remains frozen in contradiction. While Washington has watched the recent pro-democracy protests in Tehran with interest and offered tepid encouragement, a number of officials have said the U.S. isn't considering military action to derail the weapons program. Yet, in mid-June, President Bush vowed the U.S. would not tolerate nuclear weapons in Iran -- leaving it unclear exactly what our policy is.

"I think the administration is deeply split, but the one thing all factions probably agree on is that a nuclear Iran scares the hell out of them," says Jim Lobe, an administration watcher and analyst for Foreign Policy in Focus. "This administration has put itself in the worst possible position by invading Iraq with a deceptive justification [of weapons of mass destruction]. Who's going to believe them now?"

"This administration can't sustain drift on the Iran nuclear issue much longer, given the way they've defined the war on terror," says one former Middle East policy maker in Washington, who requested anonymity. "At this point the only people at the table who really have a coherent strategy are the ones pushing for unilateral military action and regime change. I don't think that's a very smart policy."

What would be the real consequences of a nuclear-armed Iran? The nightmare scenario of the "mad mullahs" jumping to attack Israel is unlikely, says John Pike, director of GlobalSecurity.org. "The regime isn't irrationally suicidal," he says. But the nuclear specter must be taken extremely seriously -- as it is by Israel, which has signaled it would consider any nuclear-armed Iranian regime, not just the current one, a mortal danger. Combined with Iran's evolving missile program, nuclear weapons would pose "an existential threat to Israel in the future," Israeli military chief of staff Shaul Mofaz told reporters on May 27. Of course, a preventive Israeli strike on Iran could precipitate a Middle East war.

Beyond containing a potential nuclear threat, hawks see considerable benefit to the U.S. in "going to Tehran." Iran, with its strategic location, represents the last major military obstacle to U.S. hegemony in the Gulf, and hawks fear it could seriously undermine U.S. plans to stabilize Iraq and Afghanistan. As one of the two remaining "axis of evil" states, and alongside Syria the last significant rejectionist, terror-supporting state in the Mideast after the collapse of Saddam's regime, Iran is a natural target for U.S. hawks.

"The Iranian vision for the Mideast becomes clear when groups it finances engage in assassination and target [regional] minorities," writes Michael Rubin of Hebrew University in a 2003 report. "The Islamic Republic views any secular Muslim government as a threat." If the Tehran regime were taken out, militant groups opposed to Israel, like Lebanon's Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad in Israel's occupied territories, would lose their strongest foreign backer. And hawks see other global security dividends in a U.S. recasting of Iran: North Korea's principal arms buyer would evaporate; and Iran, like Iraq, offers an additional source of oil to further reduce American dependence on Saudi Arabia.

As in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq, voices from Europe are sounding caution and backing diplomacy. "There is room for realpolitik to prevail," Rosemary Hollis, director of the Middle East program at London's Chatham House, wrote in Britain's Observer on June 29. "Head of the expediency council and former president Hashemi Rafsanjani is offering dialogue." But confidence in Rafsanjani's moderation may be hard to square with some of his past statements, like this one from his nationally broadcast Al-Quds Day sermon on Dec. 14, 2001: "If one day the Islamic world comes to possess the weapons like those Israel currently has, then the imperialists' strategy will come to a dead end, because even one nuclear bomb used on Israel will leave nothing left on the ground."

Was the war on Iraq just a stepping stone to Iran? There are some conspicuous similarities between Washington's recent framing of the Iran issue and the long but steady march toward war on Saddam.

"Remember how long it took before the Bush administration publicly acknowledged it was thinking about attacking Iraq?" asks Pike of Globalsecurity.org. "My surprise-free expectation is this could be the same scenario. I really question whether [internal] regime change could be effected soon enough to prevent nuclear weapons. We're on a collision course with Iran." Indeed, almost immediately after the toppling of Saddam, the administration started trotting out many of the same accusations for the mullahs: illegal weapons of mass destruction programs, harboring of al-Qaida operatives, and a brutal regime that tortures and kills its own people.

But no matter how unacceptable a nuke-wielding Iran may appear to U.S. policymakers, a U.S. invasion carries vast political and strategic risks. President Bush may not get such strong backing from the American people for another strenuous war effort, especially if U.S. soldiers continue to die daily in Iraq. By most measures, the U.S. military already looks stretched thin as it wades deeper into postwar morasses in Iraq and Afghanistan; that's notwithstanding potential conflict with North Korea, growing pressure to join multilateral missions in Africa, and Washington's pledge to help hunt down terrorists in any number of other global hotspots. And another U.S. attack on a Muslim state would enrage much of the Arab and Muslim world and threaten to completely unravel America's already shaky relations with Iraq's Shiites, who make up the majority of the country. (Shiism is the dominant religion of Iran.)

To date, discussion on the Iranian nuclear issue has ranged from rallying international support to pressure the regime into accepting stricter, more frequent inspections -- an approach favored by Russia and the European Union, which are more tied to economic trade with Tehran than the U.S. -- to the possibility of "surgical" air strikes, such as the Israelis carried out on the Iraqi nuclear reactor at Osirak in 1981.

Pike of GlobalSecurity.org thinks both options are untenable. Tougher inspections only work in a case like South Africa's, he says, when there's total voluntary compliance: "It could work if Iran wants to cough up its clandestine nuclear weapons program in an act of contrition. That just isn't going to happen." A 2002 report by Chen Zak of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy similarly discounts the updated inspections approach: "Even in the unlikely event that Iran decides to ratify the [newer] protocol, it's highly improbable that the IAEA would be able to detect illicit activities in undeclared sites," he wrote. Technically speaking, the Iranians are playing by the rules for now.

Isolated air strikes would be risky, continues Pike, primarily because Iran's suspected weapons program bears no comparison to Iraq's in 1981 and could well survive such an assault. "The danger of an Osirak-type strike is that you don't get everything," he says. "What if some of the above-ground facilities are just decoys, and the real program is hidden in some magic mountain somewhere? This is why all these new facilities are so troublesome. Until recently the Iran nuclear weapons program basically appeared to be the Bushehr problem. Now it's starting to look an awful lot like Pakistan and North Korea: multiple programs at multiple locations, some of which are known, others which are not."

Leverett of the Saban Center also thinks the odds of military conflict are going up, but agrees with Pike: "I'm not confident the U.S. really does have a unilateral military option to take out the Iranian nuclear program."

So how about a revolution instead? Iran has a nascent pro-democracy movement, and Washington has an interest in fomenting regime change. Could a nuclear crisis hasten such change?

Human rights activist Ramin Ahmadi, an Iranian-American medical doctor in Connecticut, has been an active dissident and human rights campaigner since he fled Iran two decades ago. He says he maintains daily contact with families and colleagues in Iran, including several reformist intellectuals within the regime. "Nuclear weapons were never an issue [for most Iranians] until recently," Ahmadi says. "Now people are very aware that if the regime is close to having a nuclear arsenal, it could provoke the U.S. into military confrontation. That could, of course, destroy the Islamic Republic, which many people are interested in. We know the world is paying attention to this issue, and we're asking, 'How can we use this to our advantage to get rid of the regime that we don't want?'"

The mullahs, of course, will attempt to play the nuclear card to their own advantage. On July 1, the U.K. Guardian reported that, under growing international pressure, "Iran appeared to soften its stance on allowing snap inspections of its nuclear program" by inviting the International Atomic Energy Agency back into Tehran. Mohammed El Baradei, the IAEA director, visited the country on July 9 to address "technical problems" with Iran's program. In the past, July 9, the anniversary of five days of bloody uprising at Tehran University in 1999, has been marked by turbulent street protests -- and widespread demonstrations in June set the stage for more this year. Ahmadi questions the Iranian government's motives in inviting the inspection: "They timed this visit purposely to divert the media's attention away from the student protests," he says.

(Through late Wednesday night in Iran, world media covered El Baradei's visit, with lesser reports of sporadic clashes on Tehran's streets. Some student protests were reportedly cancelled in the face of heavy police presence.)

In this tense climate, some of the regime-change discussion in Washington's hawkish circles sounds oddly conflicted: "America's role in the world is to support democratic freedom fighters against nasty tyrants," says Michael Ledeen, a resident scholar at the right-wing American Enterprise Institute. "Iran is now in a revolutionary condition. It fulfills every requirement: social, economic, political and existential. Damned if I understand how, when thousands of Iranian demonstrators are rounded up, tortured and killed, nobody says 'boo.' Where the hell is Kofi Annan, or Amnesty International? The mullahs are as nasty as any regime you can find. Why all this mealy-mouthed silence? Why is the State Department trying to make deals with these people?"

Ledeen concluded in a June 2002 AEI report, "The Iranian people are probably the most enthusiastically pro-American in the Islamic world, and would love to see an active American presence in their country." Still, Ledeen emphatically dismisses the idea that the U.S. might be planning to attack Iran. "I know military action is not being considered by anybody [in Washington]," he declares, maintaining that a disaffected Iranian population is poised to erupt. "The elected government there doesn't exist. It's a joke. They have no control over anything."

Gary Sick, a top Middle East scholar at Columbia University who served on the National Security Council in the late '70s when the Khomeini revolution rocked the Carter administration, is less sure of the prospect for an "easy," internally sparked transformation of Iran's government. "There are a lot of people in Washington seriously looking for a revolution on the cheap," he cautions. "They figure that by the U.S. simply making periodic statements, and with the L.A. stations broadcasting incendiary messages every night, that the people will rise up, overthrow the mullahs and replace them with a democratic government, and that basically we won't have to get our hands dirty at all. It's the equivalent of the cakewalk scenario for Iraq. It's an even more foolish analysis of what's likely to happen."

Indeed, all the U.S.-centric speculation tends to neglect what Iranians themselves actually believe.

"It's problematic, this expectation that Iranians will rise up in revolution, as if 'regime change' is written on our foreheads," says Iranian-American Naghmeh Sohrabi, a Harvard historian. In August 2000, Sohrabi returned to her native country to live for two years. "After Bush's axis-of-evil speech, I would hear a lot of cab drivers say, 'I wish the Americans would come with the bombs and rid us of this regime.' But I think if the U.S. did attack, how happy people would actually feel is a completely different issue," she says.

According to Sohrabi, such ambivalence goes back a half-century. "If there's one moment in modern Iranian history that everybody is moved by and has an opinion about, it's the 1953 coup. Mossadeq [the then prime minister toppled in a CIA-backed overthrow] is the most popular Iranian figure, by far. He's considered the first independent Iranian nationalist. He was no lackey for any government. So this is telling; even though many people openly welcome U.S. support, I think it's more like saying, 'May there be a curse on your house.' When you dig down deeper, it may be an expression of anger and frustration more than an actual desire."

Sohrabi, too, scoffs at the polarized policy debate in the U.S. "It's either an American attack or a 'revolution,' and it makes no sense to me," she says. "It takes more than a few days of a few thousand people taking to the streets in a capital of 11 million for a revolution to happen. And who says there has to be one? There are many other possibilities in between [for change]."

Like Ledeen and some other Washington hawks, Ramin Ahmadi supports the idea of strongly encouraging revolution. He says that much of the Western media is missing the depth of misery and desperation in Iran, and that people there would do "just about anything to change the government."

But Gary Sick points to the potential cost of the U.S. sponsoring rebellion without committing troops and money.

"If Iranians took to heart American encouragement and rose up against the regime, the security forces would crack down on them brutally, a lot of people would be killed, and Khatami and the reform movement would be thrown out. When they ask, 'Where are the Americans?' are we really going to intervene on behalf of these people? We think we can do this without cost, but the cost is in fact enormous," Sick says. "I remember vividly what happened in 1991 after the Gulf War when we openly called for the Kurds and the Shi'a to rise up against Saddam Hussein. They did, and we said, 'It's your problem,' and tens of thousands were killed."

Further complicating things, there is no guarantee that an Iranian revolution would mean an end to Iran's nuclear program, or its hardline foreign policy.

Sick believes the U.S. must approach the goals of nonproliferation and regime change in Iran with a better-balanced, more nuanced policy: "Iran has to see some real benefits, to be made to feel better about regional security. That's not an easy task, while somehow also satisfying our requirements."

Flynt Leverett advocates a similar strategy: "We have to put forward the carrot and the stick at the same time," he says.

Meanwhile, the Bush administration's outlook remains muddled, unless you choose to interpret the incoherence as a calculated preface to the next war-on-terrorism campaign -- a deliberate courting of long-term crisis that might ultimately give the American public much more of a taste for an Iran war.

"I heard Karl Rove quoted the other day as saying 'good policies are good politics.' I think this administration believes a policy of perpetual war is a good one," says GlobalSecurity.org's Pike. "The notion that they're going to be gun-shy from here -- many are arguing that now, but it's not evident to me that those who have their fingers on the triggers share that view. I think they believe they have a rendezvous with destiny."

Indeed, arduous diplomacy may not seem attractive to an administration emboldened by two impressive displays of U.S. military might.

"There are people who really want to see the U.S. engaged in a battle with Iran, to overthrow the regime and install their own preferred ruler. I hope they think seriously about the danger of that, especially with 150,000 troops bogged down in Iraq and apparently not leaving anytime soon," says Gary Sick. "It would mean taking on another task that would make Iraq really look easy by comparison."

Shares