On Wednesday afternoon this week, elementary school children and their parents in the Boston area who were watching public television got to see perhaps the only educational cartoon ever forced to fend off efforts to ban it. Given the Bush administration’s success in keeping the show off the air — except in Boston and a handful of other PBS markets — it might not be the last time, as cultural conservatives and the Public Broadcasting System seem destined to continue to do battle over programming. And considering how quickly PBS conceded defeat this round, that battle may become increasingly lopsided.

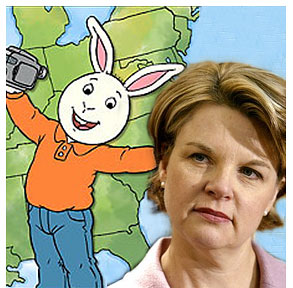

The controversy surrounding the children’s series “Postcards From Buster,” featuring a cartoon bunny who, in one episode, visits Vermont to make maple syrup and meets children from two families headed by lesbian couples, generated headlines last week when incoming Education Secretary Margaret Spellings lambasted the episode as inappropriate. Many observers likely viewed the showdown as little more than another head-shaking episode in the ongoing culture war. (The “Buster” flap erupted the same week that Christian talk show host James Dobson warned parents that a classroom video on intolerance featuring SpongeBob SquarePants “could prompt [teachers] to teach kids that homosexuality is equivalent to heterosexuality.”)

But for PBS insiders and longtime supporters, the skirmish, and the speed with which PBS backed down in the face of threats from the Bush administration, mark a new low point for the broadcasting institution and a dangerous development for the public. Low because the content of the “Buster” episode was so innocuous. And dangerous because it highlights the inside-the-Beltway environment in which PBS is forced to operate, where funding concerns often trump programming decisions, and the fear of upsetting conservatives has become a driving force.

“Political decisions now come to bear on public television, despite the fact its specific mission is not to be partisan,” says one former PBS staffer. “The conservative right, slowly but surely, is chipping away at PBS. They have Republican lobbyists counseling them, ‘Do the right thing or we can’t help you on Capitol Hill.’ It’s a chilling effect. And every time PBS gives in to them, that gives [conservatives] more say over the programming.”

According to a knowledgeable source, one outside lobbyist for PBS, Karen Nussle, the wife of Rep. Jim Nussle, R-Iowa, told executives at the network that if they went ahead and aired the disputed “Buster” episode, she would not be able to help them politically. “She’s a good representative to the Republican Congress, and if they lost her that would set the relationship back and PBS would be left exposed on the Hill,” says the source, who adds that PBS’s main lobbyist, John Lawson, president of the Association of Public Television Stations, also warned the network against fighting the administration. “He told them, ‘This threatens our relationship by making Margaret [Spellings] have to deal with this,” says the source. Lawson, who is Spellings’ brother-in-law and who attended her swearing-in ceremony this week, declined to comment for this article. Nussle did not return calls seeking comment.

Asked about what influence Nussle and Lawson might have had internally as PBS wrestled with its decision, John Wilson, PBS’s senior vice president for programming, says he never spoke to them. “I don’t seek out the advice of lobbyists.”

Even before she was sworn into office as the new education secretary, Spellings, a former Bush White House advisor, condemned the TV bunny. She afterward warned PBS about its tenuous federal funding and demanded that PBS refund the Education Department for the grant money it had contributed to the show’s production, approximately $125,000. It was an unprecedented attempt to micromanage — and humiliate — PBS.

“I don’t think we’ve ever been contacted by a Cabinet secretary about anything, let alone a particular [children’s] episode,” Wilson says.

In the wake of all the pre-broadcast hype, those watching WGBH in Boston Wednesday may have been most surprised by what they didn’t see in the “Buster” episode, titled “Sugartime!” “It was totally benign,” says Peggy Charren, the children’s programming advocate and public television pioneer who serves on the board of trustees of WGBH, the PBS station that produced the series. “I was expecting there to be a discussion about lesbian families. There was nothing. I watched the tape twice and then called over to ‘GBH and said, ‘Are you sure this is what all the fuss is about?’ The amount of information about lesbian families in the program is zero. I learned more about cows — that all cows are female — than I did about lesbians.”

Other PBS veterans agree that the Republican reaction was wildly overblown. “I viewed the episode and it’s a lot of hullabaloo about very little,” says Jeff Clarke, president and CEO of KQED, the San Francisco PBS outlet. “It’s about kids milking cows and playing in hay. It’s not about pushing any agenda.” PBS president Pat Mitchell initially agreed, giving the episode a green light after reviewing it. But four days later, on Jan. 25, she reversed course and announced that PBS would not distribute the show nationwide. The same day, Spellings’ office issued a blistering letter denouncing the program and demanding a refund of the government’s grant. (PBS will not refund any money to the Education Department but, rather, ask WGBH to create a new, replacement episode so that the “Postcards From Buster” series can still broadcast the planned 40 episodes.)

A handful of stations other than WGBH, such as KQED, WNET in New York and KVIE in Sacramento, Calif., bucked PBS’s decision and plan to broadcast the show at various times between now and March. “We decided there was no reason not to air the episode,” Clarke says.

Ever since America’s public television system was established through the 1967 Public Broadcasting Act, it has had to dodge political bullets, nearly always fired by Republicans. Despite the consistent and high-profile presence on PBS over the years of right-leaning pundits such as William Buckley, John McLaughlin, Ben Wattenberg, Fred Barnes, Peggy Noonan, Tony Brown and Morton Kondracke, Republicans have insisted for decades that the network is guilty of a liberal bias. During the early ’70s the Nixon administration, reportedly unhappy with public television’s voluminous coverage of the Watergate hearings, tried to silence the network by curtailing funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, a presidentially appointed oversight body that channels federal dollars into PBS and local stations. Originally conceived as a way to shield PBS stations from political pressure, the CPB under Nixon tried to do the opposite by exerting more control over programming decisions.

During the Republican revolution of the ’90s, the attack was more frontal, with House Speaker Newt Gingrich declaring a war on “Sesame Street’s” Big Bird and deriding PBS as “this little sandbox for the rich.” He proposed to “zero-out” its federal subsidies, dismissing the network’s supporters as “a small group of elitists who want to tax all the American people so they get to spend the money.” The offensive put PBS on notice, but politically it was a failure. So Republicans adjusted their sights. As Ken Auletta noted in the New Yorker last year, “The American right has stopped trying to get rid of PBS. Now it wants a larger voice in shaping the institution.” And it’s clearly getting that voice.

Last summer, the CPB (whose senior vice president for TV programming, Michael Pack, enjoys close ties to the Bush White House) announced funding for two new public affairs programs, each hosted by conservative commentators who were already widely expressing their views on mainstream media outlets: Tucker Carlson, formerly of CNN’s “Crossfire,” and Paul Gigot, editor of the Wall Street Journal’s editorial page (a page that in the past has argued for the complete withdrawal of federal funding for PBS). The CPB also announced there would be no funding for the TV newsmagazine “Now,” hosted by liberal advocate Bill Moyers, which some Bush-appointed members of the CPB board dislike. According to the New Yorker, during a CPB meeting last winter, “board members attacked Moyers as partisan. One member reportedly screamed, ‘You’ve got to get rid of Moyers!'” Moyers has since left the weekly show, which has also been cut from one hour to 30 minutes.

Yet relations between PBS and Republicans have been surprisingly cordial over the last couple of years. Laura Bush, a former librarian, has spoken warmly about PBS’s children’s programming and embraced the Ready to Learn initiative, an effort to help prepare kids for school. And against the backdrop of congressional hearings on indecency in commercial broadcasting and bipartisan opposition to further media consolidation, PBS has been able to stake out a unique, and largely welcomed, territory in the eyes of Congress. PBS has also worked at ingratiating itself with Republicans. It tapped Gingrich as its keynote speaker in 2003, when PBS station managers made their annual pilgrimage to Washington to schmooze with politicians and ask for funding. That’s one reason why Spellings’ full-throated attack on a cartoon bunny caught so many people off-guard.

“Postcards From Buster” is a spinoff of the award-winning animated children’s program “Arthur.” In each episode Buster, a high-strung bunny, visits real-life families in towns around the country — such as Park City, Utah, and Whitesburgh, Ky. — to learn about local customs and different cultures. During Buster’s trip to Vermont, he learns about milking cows and making maple sugar while briefly meeting two families headed by gay parents. The Education Department contributed $23 million to the Ready to Learn program, and $5 million of that went to “Postcards From Buster,” which targets 6-to-8-year-olds. Officials at the Education Department knew ahead of time that the pair of lesbian moms appeared in one episode because WGBH, upon request, sent over a rough cut of the series in early January. “It’s not common, but we work cooperatively with them,” says Jeanne Hopkins, a spokeswoman for WGBH.

On Jan. 21, PBS announced that its broadcast of the “Sugartime!” episode would be postponed until March 23 so stations around the country could preview it. Some outlets, such as Alabama Public Television, immediately balked on airing it. APTV spokesman Mike McKenzie said that introducing the issue of gay marriage, even indirectly, “would violate the trusted relationship between parents and the stations.”

But on Jan. 25 PBS reversed course and opted to not distribute the episode nationally, a rare move. (Stations that choose to air the show will get it from WGBH.) Then, a few hours later, came Spellings’ attack. “It’s sort of frightening that on her second day in office the secretary of education finds a half-hour children’s program to complain about,” Charren says.

Wilson, the PBS programming executive, says the show was yanked because it failed, adding that it failed, ironically, because the gay mothers played too small a role in the episode. “If the goal was to explore alternative family structures, we would have done it thoroughly and thoughtfully. Instead, the episode opened the door to a sensitive issue and then didn’t fully explore it, [which] then lets parents down.” Of course, if Spellings found a pair of lesbian mothers in the background objectionable enough to demand a refund, who knows how far she would have gone if PBS had produced a full-fledged exploration of gay parents in its children’s programming.

It’s possible the lobbyists are right, and that yanking “Sugartime!” off most PBS stations will help preserve the network’s working relationship with those who have the power to cut funding, or hold hearings on the network’s “bias,” as has occurred in recent years. But Charren wonders at what price. “I don’t think you can afford to have a relationship like this,” she warns. “It doesn’t help PBS at all to have the public think that whenever the White House snaps its fingers, PBS jumps. People don’t give money to PBS in order to have the White House tell it what to do.”