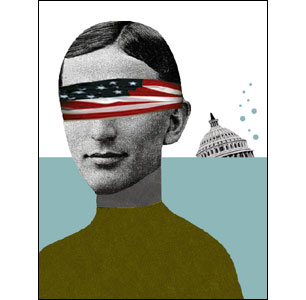

Is the American public too ignorant for democracy to work? That’s not intended as a smarmy, elitist question. It is, in fact, one that political scientists take very seriously.

While the press corps has been clucking over George W. Bush’s inability to name the general behind the coup in Pakistan, a potentially bigger story has gone unnoticed: Many Americans barely know who the leaders of their own country are. One of the dirty little secrets of public-opinion research is the jaw-dropping apathy and general boneheadedness of the electorate.

A poll by the nonprofit Pew Research Center, released in September, gently touched on this issue. The poll showed that 56 percent of Americans could not name a single Democratic candidate for president. Things weren’t better for the Republicans: Only 63 percent could recall the name “Bush.” (It’s a fair bet, moreover, that some of the people who came up with George W.’s name were thinking of his father.)

Howard Kurtz, the Washington Post media critic, declared the Pew results “stunning.” He and others suggested, however, that there was something special about this year’s race that was boring voters. (Insert your own Gore joke here.)

Yet one of the most consistent findings of public-opinion research is that the majority of Americans have long found politics about as exciting as a PBS documentary on the great crested grebe — and they pay a corresponding amount of attention to it. Consider the following, drawn from an almost endless number of examples that political scientists have turned up over the years: One month after the Republican revolution in 1994, in which conservatives, led by Newt Gingrich, finally took control of the House of Representatives, 57 percent of the electorate did not know who Gingrich was. Despite massive coverage in every newspaper in the country, and on every news program, the vast majority had never heard of the Contract with America. On a typical election day, 56 percent of Americans can’t name a single candidate in their own district, for any office.

Nor is this a new development or the product of young minds warped by MTV. In 1964, at the height of the Cold War, only 38 percent of Americans could say for sure whether the Soviet Union was a member of NATO. Most had no idea that the United States was pledged to go to war if West Germany was invaded. It’s not just the people who don’t vote who are uninformed, either — not that that would exactly be reassuring. Only a tiny sliver of active voters show even passing familiarity with the kinds of policy debates that elites take for granted.

When the public does have “opinions,” moreover, they are often self-contradictory. It’s well known, for example, that Americans hate Big Government. But, at the same time, most Americans also think the state should spend more on just about every public program you can name, except for welfare. Lest you think it is only ugly Americans who can’t think straight, polls show that the sophisticated, government-fetishizing French are just as out of it.

The subject of voter ignorance was first explored in depth by political scientists in the 1950s and 1960s, but it has inspired a fresh wave of scholarship in the past decade. The scholarly journal Critical Review, in fact, devoted its entire fall 1998 issue to it — a nice kickoff to the current presidential race. The topic of voter ignorance “is so important,” wrote the journal’s editor, Jeffrey Friedman, in an introductory essay, “that if we were to focus on it intently, it would overturn our understanding of politics.”

Friedman points out that almost all talk about public affairs assumes that citizens follow politics closely. When Ronald Reagan was elected, most pundits saw it as an across-the-board mandate for the conservative agenda, a massive lurch rightward. Clinton’s victory was then characterized as a shift back to the center. Clinton’s surviving the impeachment was a sign to many that the American public had lost its moral compass. In fact, however, most people base their votes, and their answers to polls, on only the vaguest feelings about how the economy, or life, is treating them.

Clearly, voter ignorance poses problems for democratic theory: Politicians, the representatives of the people, are being elected by people who do not know their names or their platforms. Elites are committing the nation to major treaties and sweeping policies that most voters don’t even know exist.

One side product of voter ignorance is a gap between what the press writes about campaigns and what people want, or need, to know. Political journalists travel on buses and planes with candidates and shmooze all day with their staffs. The nose-to-the-glass perspective leads to lots of front page stories about which campaign aide is up or down in his boss’s eye, who among the staff are feuding, and who dresses the candidate. “The stuff that never filters down to voters is the inside-the-campaign stuff — stories about why they are running one kind of ad, as opposed to another,” says Larry Bartels, a professor at Princeton University who has studied uninformed voters. He has found that incumbents get a 5-percentage-point boost from voter ignorance, because the fallback position of uninformed voters is to pull the lever for a name they’ve at least heard of.

Awareness of just how uninformed voters are should lead us to take polls with a grain of salt, Bartels notes. At this early point, the opinions on which they are based are so thin that the results are close to meaningless. (The polls can, however, assume a life of their own: People will start to form real opinions based on the dubious early polls — and will jump on the Bush bandwagon, for instance.)

Some scholars say their own views of campaigns changed when they started studying voter ignorance. “You often see the press and pundits saying that some small statement by a candidate will have a profound effect on how people perceive him,” says Ilya Somin, a graduate student in government at Harvard University, who contributed an essay to the Critical Review forum. “I’m not saying that never happens, but I’m more skeptical. Most statements candidates make are not noticed by most voters. The candidates and their staffs may understand that, but the press may not.”

In an attempt to avoid the elitist overtones of voter-ignorance theory, a number of political scientists have labored to show how democracy manages to limp along despite rampant cluelessness. They have offered several “solutions.” It may be, some have said, that people use rough rules of thumb to guide their decisions. Workers might not understand debates over interest rates or monetary policy, but they vote for incumbents whenever their bank balance is high. Or it’s been years since they followed politics, but they’ve trusted the Democrats since Truman’s day, and always vote for them. Or they might follow the lead of the handful of people in their circle who do monitor politics — that loudmouth at the country club, say, or the union foreman. These might not actually be terrible ways of making decisions that line up with your own self-interest, some researchers assert.

On a more technical note, some academics argue that a phenomenon called the “miracle of aggregation” sweeps in at the end of the day to save democracy. Many voters are ignorant, this line of thinking goes, but the ignorance is distributed randomly across the political spectrum. Therefore — here’s the miracle — only the votes of the informed end up making a difference. Plenty of questions remain about this theory, such as: Why assume that ignorance leads to random decision-making? Maybe elites, demagogues or the press can sway uninformed voters in one direction, thereby drowning out the votes of the informed minority.

Scholars diverge on how significant voter ignorance is, but few take as apocalyptic a view as Harvard’s Somin. He argues, in his Critical Review essay, that the combination of uninformed voters and — this is his own twist on the debate — the sheer size of government is proving fatal for democracy. Voters have a hard enough time remembering the candidates’ names and their parties, in his view; they simply have no idea what’s going on in the government’s 14 cabinet-level departments and 57 regulatory agencies — or how the trillions of dollars in the budget are being spent.

Since people can’t expand their brains, Somin proposes shrinking the state — turning back the clock, in effect, to the 19th century. In the 1800s, he argues, the American government handled only a few key issues, including war and peace, slavery, territorial expansion and federal banking policies. Typically, only one of these issues moved to the front burner at any given time. The public, therefore, was able to wrap its collective mind around each one as it came along, processing extremely complicated arguments. Witness, he says, the Lincoln-Douglas debates on slavery. (A skeptic might point out, however, that we don’t have any evidence that the public understood Lincoln’s and Douglas’ arguments any better than it does NAFTA.)

It may be that asking whether democracy works well is the wrong question. A better one is whether democracy prevents the worst sort of governmental abuse and oppression. Here the political scientists’ view is more hopeful: Politicians’ knowledge that the many-headed monster can be roused if the state steps too far out of line may be enough to keep the leaders in check.

This isn’t exactly a civics-textbook view of democracy. But thinking along these lines might bring us closer to understanding how our democracy actually functions — how it works in the real world, not in Rousseau or Locke. That people feel free to follow football instead of Bill Bradley’s health-care proposals may be a sign that things could be a lot worse than they are. That the press writes about Gore’s earth tones and Bradley’s spare tire shows that it, too, doesn’t think there’s all that much to worry about. (That’s a whole lot less excusable, given that so much of the press’s self-definition involves fostering an engaged citizenry.) Of course, such sunny hypotheses elide the other darker possibility.

Smug complacency could also be a sign that the public and the press are being duped into thinking things are swell when they aren’t. For activists and politicos, the lesson is probably that you can make all the careful, lucid arguments you want, but you have to catch people’s attention first. And that, to say the least, is an uphill battle.