The public debate over gun policy has fallen into a somewhat predictable pattern. A tragic shooting — like Jared Loughner’s rampage in Tucson, Ariz., a week ago — prompts outrage from across the political spectrum. After an immediate cathartic and emotional response, the two sides in the gun debate fall into their familiar postures. Proposals for new gun regulation are made, prompting push-back from gun rights advocates, who circle their wagons, issue warnings about the threats to our Second Amendment rights, and — in a more recent twist — begin calling for a relaxation of existing gun regulation so that citizens can more easily defend themselves.

Although the Second Amendment is often invoked in this debate, the dynamics of America’s battle over guns have almost nothing to do with either the historical Second Amendment bequeathed to us by the framers, or even the more individualistic Second Amendment conjured by the present-day Supreme Court of John Roberts in two controversial decisions. The original Second Amendment was the product of a world in which a well-regulated militia stood as check against the danger of a professional standing army. The framers certainly believed in a right of self-defense, but most viewed it as something that was so well-established under the English common law that there was no need to write it into constitutional law. Even among those eager to secure a bill of rights, the dominant view (with a few notable exceptions) was that the right of self-defense was best left to the care of individual states to regulate as part of their criminal law. Even the more expansive modern notion of the Second Amendment popular today (an interpretation endorsed by the Roberts court) permits ample room for reasonable regulation. American courts are still wrestling with how to implement this new model, but most legal schools of thought agree there’s plenty of room for regulation.

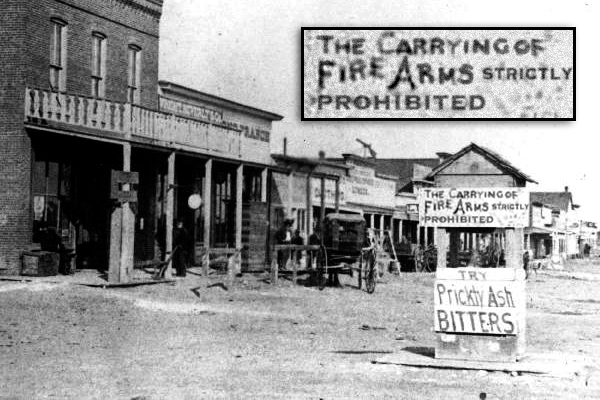

If not from the founding generation, where did our modern notions of the Second Amendment come from? A more individualistic conception of the right to bear arms did emerge at the end of the 18th century, and it gained a stronghold in the early decades of the 19th century. The passage of the first true gun control laws in the 19th century, a response to the proliferation of cheap handguns for the first time in American history, actually helped strengthen this new gun rights ideology. Then, as now, gun violence was largely a problem about handguns, not long guns. Not surprisingly, the efforts to ban guns back then led to the first clear defenses of a modern-style Second Amendment right to bear arms unconnected to the militia. Some of the new state laws wound up in state courts, and judges divided over how to interpret them. Some jurists saw them as unconstitutional, while others upheld them. The dysfunctional modern debate over firearms was born out of this struggle and has nothing to do with the original Second Amendment. The notion that regulation is antithetical to the Second Amendment has no basis in history or law. As long as there have been guns in America, guns have been regulated. Even at the height of the Wild West in Dodge City, gun regulation was a fact of life.

Given that Americans have been debating the merits of gun rights and gun regulation since the era of Andrew Jackson, one might wonder if there’s any hope for progress on this contentious issue. Ironically, the recent decision of the Roberts court to reinterpret the Second Amendment as an individual right that guarantees access to a workable handgun in the home for self-defense might help change the terms of debate. In the face of this, the old slippery slope argument that regulation is the first step toward confiscation simply has no meaning anymore. (Never mind that the slippery slope metaphor was always backward; it was always an uphill battle for gun regulation, not a slippery slope.) The decades-old handgun bans enacted by Washington, D.C, and Chicago have been taken off the table. Even more critical to the future of the gun debate are new insights from more than 30 years of academic research on gun policy. The future of gun policy in America rests on two incontrovertible facts: Guns are deeply rooted in American culture, and guns have always been subject to robust regulation. The real question, then, is what sort of regulation is likely to produce a meaningful reduction in gun violence without imposing undue burdens or costs on gun owners. This is where the new research on guns in America offers some hope — if, that is, we can summon the political will as a people to enact any new gun laws.

The European-style handgun bans recently struck down by the Supreme Court reflected three-decade-old policy thinking about guns. But two generations of academic research have pointed us toward a new paradigm for gun regulation. Most of this innovative gun research looks to the marketplace, not bans, as the primary means to reduce gun violence. Rather than simply banning handguns, an unpopular policy in most parts of the country, the new research suggests a more targeted strategy, with the primary goals being to prevent guns from moving into the black market and to restrict the access of dangerous people — including those with mental illness — to firearms. Rather than ban handguns, the new model only uses bans for a very narrow range of particularly dangerous items not essential for sport or individual self-defense: high-capacity magazines for semi-automatic weapons and a few highly unusual weapons such as high caliber sniper rifles. Many would also argue for providing tax incentives to encourage responsible gun ownership practices, like enrolling in gun safety courses or purchasing gun safes. The goal would be to provide both carrots and sticks to gun owners.

The gun debate has long been dominated by slogans, including this perennial favorite: When guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns. The standard argument of the gun rights movement is that criminals will not obey gun laws, so why penalize law-abiding citizens? But this assumes that criminals are the only non-capitalist actors in our economy. Given that most criminals are not Zen Buddhists, blissfully unaware or unconcerned about material things, the argument is clearly false. Criminals are not immune to the market, and policies can be crafted that take advantage of this fact to reduce, but not eliminate, all gun violence.

Gun researchers point to the impact of academic studies of automobile fatalities as a model for future gun policy. The goal of such policies ought to be to enact laws likely to reduce deaths and injuries with the lowest possible costs to legitimate gun users. Obviously, new policies will not be cost-free. New laws will mean some additional costs for gun owners, and likely some modest inconveniences, but at least some of these expenses could be offset by tax incentives for safe gun practices. It’s important to recognize that Americans have been shouldering the direct and indirect costs of gun violence for as long as there have been guns. The advantage of this new economic model is it acknowledges gun owners’ rights and restricts new policies to those likely to produce a reasonable effect without imposing a significant burden on gun owners. Reframing the gun debate in economic terms has another advantage — it moves public discourse away from the rhetoric of demonization in which gun nuts battle against gun grabbers. The terms of the discussion should be shifted into the more analytical and dispassionate realm of economic analysis. If nothing else, reducing the rhetorical excesses of the gun debate would be a major step forward.