It’s a staple of TV dramas — the photograph of a suspect is plugged into a law enforcement database, and a few minutes later: presto! We have a match! Facial recognition for the win!

Except the magic didn’t work in the case of the Boston bombers, according to the Boston law enforcement authorities. The surveillance society did a face plant.

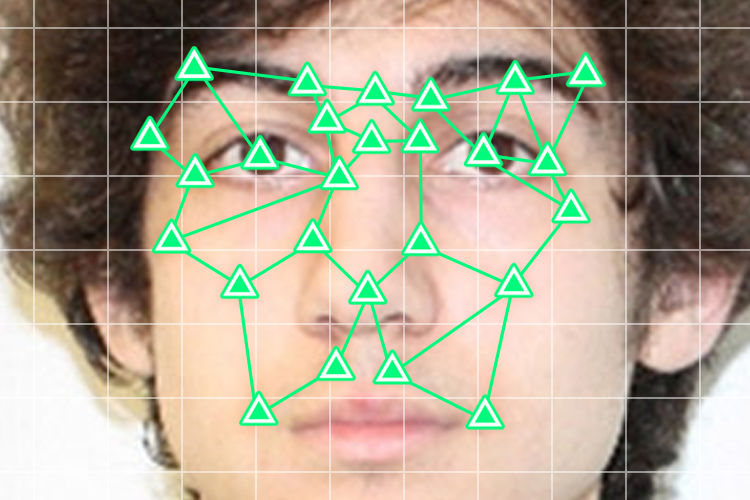

What happened? I called up Carnegie Mellon computer scientist Alessandro Acquisti, an expert in online privacy who has conducted some provocative research involving facial recognition. In a series of experiments, Acqusti and his fellow researchers were able to use “off-the-shelf” facial recognition software to identify individuals by comparing photos from a dating site, or taken offline with camera phones, with photos uploaded to Facebook. The researchers were also able to figure out a startlingly large amount of personal information about the people they managed to identify. But if Acquisti could do it, why couldn’t the FBI?

Acquisti explained to Salon what he thinks might be happening on Monday morning.

The Boston police commissioner says that facial recognition software did not help identify the Boston bombing suspects, despite the fact that their images were included in public records databases such as the DMV. Can you speculate as to why that might have been the case?

There are three or four potential hurdles that all types of facial recognition software face when we try to apply them in real time on a mass scale. Although before describing these hurdles I will also add that I do not consider any of these obstacles or hazards systemic. Meaning, unbreachable.

The first is image quality. If you look at the images which were posted on the Internet of the bombing suspects, they were usually taken from far away, which means that when you zoom close to the faces, the faces are usually out of focus. So, you don’t have a very good image to start from. The images which were available were not of good quality.

The second hurdle is the availability of the fine facial data on the identified faces that you already have in your existing databases. There are number of different databases which can be used. Some are public databases, such as DMV, and some are private-sector databases, such as online social media databases. I would argue that it is increasingly the case that the latter are better than the former for the purpose of facial recognition. The reason being, the more images you have of someone’s face, the more accurate the mathematical model of that face you can produce. If you’re the DMV, and you only have one very good frontal shot of a person, that may not be as good as having 10 photos from slightly different angles of that person’s face. Together, those 10 photos allow you to create a more accurate model of that person. Private databases involving social media have better databases for facial recognition, which brings up the issue of whether and under what conditions the Facebooks of the world would share those images with investigators.

The third issue — which I don’t think played a role here — is computational costs. In the experiment we did three years ago, we were able to find results in real time, with a delay of just a few seconds, because we were working with databases of only a few hundred thousand images. When you are working with a database of say 300 million images, one picture for every U.S. adult, more or less, even using the kind of commercially available cloud computing clusters that we were using for our experiment, it’s just not enough to give you results in real time. Our estimates suggested that, if we expanded to a database of 10 million images in our experiment, it would have taken four hours to find a match.

That said, I suspect that this would not be too much of a problem for the NSA, if the NSA got involved in this.

The last problem is that, even if you have enough computational power, and you can do not just hundreds of thousands of face matches or face comparisons in a few seconds, but millions, or tens or hundreds of millions, you still have the problem of false positives. When you start working with databases that contain millions of faces, you start to realize that many people look similar to each other. We human beings are very good at distinguishing people who look the same, but computers are not that good right now.

However, what I argue makes people so good at distinguishing similar faces is that we humans don’t simply do facial recognition when we recognize other people. We do a holistic recognition of the entirety of the person, based on how they are dressed, how they are walking, and on where they are geographically and physically. Most of current facial recognizers do exactly only that: face recognition. But I argue in the not so distant future, in fact, pretty soon and perhaps already now in some researcher’s lab, facial recognition will start to put images together with metadata such as how tall you are, what is your favorite way of dressing, where were you most likely to be in the last 24 hours. From a social network, for example, I can see the IP address on which you connected three hours ago, and I can see, because there are so many photos of you, how tall you are, whether you have gained weight or not, your dressing style. It won’t be long before we have ways of recognizing you which do not rely solely or primarily on points in a mathematical model of your face.

These three or four hurdles — the quality of images, the available data, the computation costs, and the metadata are hurdles which right now still separate current facial recognizers from the ability of truly doing real-time mass scale recognition. But five years out, 10 years out, 15 years out …

What’s going to change?

In the case of quality, every year there is a new generation of phone cameras which has higher resolution than the year before. I sent you an image of a crowd of fans gathered to support the Vancouver Canucks that shows what you can do when you have really, really high resolution cameras which are able to, even from a distance of hundreds of meters, capture with very high focus and very high detail all the elements of someone’s face.

As for the issue of availability of photos — as I said, I think whether access is only limited to databases such as the DMV or whether there is access to social media photos will be key.

Computational capabilities will become more and more powerful over time. That is the direction that computational power has gone for many, many years.

And as for the metadata issues, I suspect that research on facial recognition will become more and more research on identity recognition. We will combine not just facial recognition but all this additional data. Imagine if you have access to online social network data, and you could screen out the images you wanted to look at by, for example, all social media users who were not connecting from an IP address in the Boston area over the past three days. Now you have a much smaller subset of images to look at it. Then you can filter out females because you believe these guys are male, then you filter based on height, because from some certain shots, although you cannot see the faces you can estimate the height in other ways. This reduces, arguably, the number of false positives. All of these reasons are why I’m saying these four hurdles are not congenital to the technology and will forever limit it. For better or worse, depending on your opinion on these matters, the accuracy of facial recognition will keep improving.

Looking forward, are there reasons why improved facial recognition should worry us?

I am concerned by the possibility for error. We may start to rely on these technologies and start making decisions based on them, but the accuracy they can give us will always be merely statistical: a probability that these two images are images of the same person. Maybe that is considered enough by someone on the Internet who will go after a person who turns out to be innocent. There’s also the problem of secondary usage of data. Once you create these databases is it very easy to fall into function creep — this data should be used only in very limited circumstances but people will hold on to it because it may be useful later on for some secondary purpose.