Publishing other people’s work is a hell of a lot more enjoyable than publishing your own. Publishing your own work is fraught with complicated, even tortured, feelings. Invariably you believe that you’ve failed. That you could have done better. That if you were given another month or another year, you would have achieved what you set out to do.

Actually, it’s not always that bad.

But usually it is.

Publishing someone else’s work, though, is uncomplicated. You can be an unabashed champion of that work. You can finish reading it, or finish editing it, and know that it’s done, that people will love it, and that you can’t wait to print it. That feeling is strong, and it’s simple, and it’s pure.

That’s what’s driven McSweeney’s for fifteen years now—far beyond the four or eight issues we originally thought this journal would run. We thought the fun of it would end after a year or so, but that feeling, of finding a new voice, or a new piece by an established voice, and setting it into type and printing it and sending it into the world, is still just as good as it was back when we started in 1998.

Back then, it was me opening submission envelopes in my kitchen, and being astonished that anyone would trust this new quarterly with their work. When I was the only one reading the submissions, I was an easy audience. I was so overwhelmed with the whole thing that I pretty much accepted every other story. And then I couldn’t wait to get them into print.

I would usually accept a story and lay it out the same day. If I couldn’t get a digital version of it soon enough, I would just retype the whole story and lay it out that night. This is what I’m talking about: this simple and good feeling of knowing you’ll be able to introduce a new writer to new readers.

Early on, most of the writers in McSweeney’s were lesser known, or were starting out in their careers. After a few issues, we began getting work from some established authors—even without asking, which was startling—and since then, our goal has been to balance these known quantities with the newcomers, and balance both of them with an eye toward occasional experimentation— some of these experiments improbably successful. Sometimes these commissions were simple acts of matching a great writer to unusual subject matter. Thus we sent Andrew Sean Greer to a weekend NASCAR rally in Michigan. Sometimes these commissions were based on iffy notions that yielded great results—for example, when we asked dozens of writers to each write a short story in 20 minutes. In one issue we asked our writers to write stories based on the notebook jottings of F. Scott Fitzgerald. In another we asked them to help resurrect dead forms like the pantoum and biji.

But most of what we’ve published over the years has simply come through the mail. We still open every submission envelope, and each time we do, we want to be surprised, we want to be reawakened. I’m rarely the person opening these envelopes anymore, but the other day, while talking to the volunteer readers about the responsibility entrusted to them, I found myself using the word sacred. It was hyperbole, I’m sure, but here’s what I meant: it takes a particular mix of madness and courage to write short stories—they do not pay the rent, they are not widely read—and it takes even greater courage to put them in the mail, submitting them for judgment by strangers. So thinking about these senders, batshit-crazy and full of hope and dread, and the fact that they would entrust our readers to judge their work, and for us to print their work, I used the word sacred. It still seems right in some way.

Art is made by anarchists and sorted by bureaucrats. Thus, over the years, there have been a few bureaucrats who, feeling the need to categorize and label, have posited that McSweeney’s has some house style. But this is not the case. Even the earliest issues, which even I assumed did lean toward the experimental, always balanced these formal forays with more traditional storytelling. Issue Three, for example, included a story by David Foster Wallace that we ran on the spine, but it also featured a 25,000-word essay about a writer’s correspondence with Ted Kascynski. This balance has held true ever since. We’ve sought to publish the best work we can, no matter its genre or approach or author. We’ve published everything from oral histories from Zimbabwe to experimental prose-poems from Norway. The only thing common to all in this collection, to the work in every one of our 45 issues so far, is that the work was good and told us something new.

Some years ago, I was in Galway, Ireland, and happened to meet a man named Timothy McSweeney. I got to know him and his wife, Maura, who also had the last name McSweeney. We talked about a writer she liked, and she said, “He writes like he’s seeing the world for the first time.” That’s what we look for—writers who make us feel like they’re seeing their world, whatever world that is, with fresh eyes, and who allow us to experience it through their words.

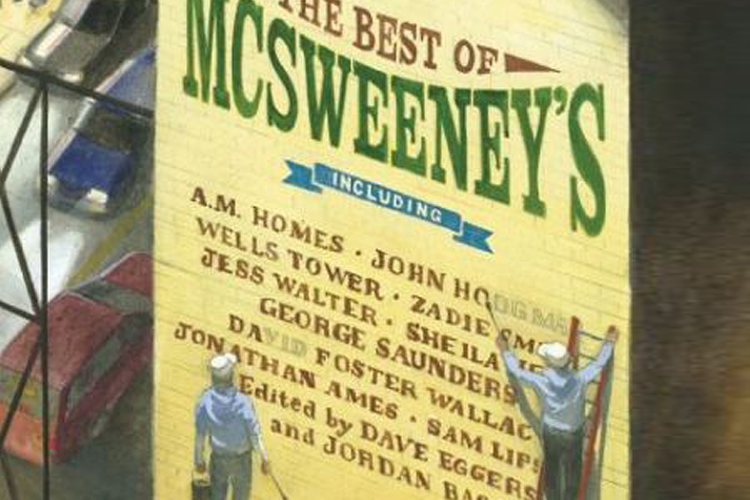

Our new collection is called Best of, and to some extent that’s true—this volume includes some of the best writing we’ve put out—but there are many dozens of great stories missing from these pages. This anthology clocks in at over 600 pages, and getting it down to even that bloated number was tough. Though we could have filled 1,000 pages with great and more or less traditional short stories, we sought here to represent both those stories and also the range of special projects and commissions that we’ve published over the years. So you’ll see samples from our genre-fiction issue, edited by Michael Chabon, from our comics issue, edited by Chris Ware, from our dead-forms issue, edited by two interns, Darren Franich and Graham Weatherly, and our South Sudanese fiction issue, put together by Nyuol Tong. Undergirding it all is plain great writing.

When I think about fifteen years of McSweeney’s, the overwhelming emotion I feel is gratitude. For the staff who has kept the machinery working, for the readers who have supported us, for the bookstores who have stocked us, for the writers who have given us their stories. It’s a strange and improbable thing when a literary quarterly lives this long, and we don’t take it for granted. Thank you kindly.

Excerpted from “The Best of McSweeney’s.” Published by McSweeney’s Books. Copyright 2013. All rights reserved.