is is a story about a man named Rudolf Ivanovich Abel. He was a colonel in the KGB—a master spy, a mole deeply embedded in the United States, and the central hub of a massive, all-consuming espionage network that threatened all that we hold near and dear.

Well, that’s not totally true.

He was also Emil Goldfus, a kindly, unassuming, retired photofinisher and amateur painter, developing his craft with a group of fledgling Realist artists living and working in Brooklyn in the 1950’s.

Of course, that’s not entirely true either.

* * *

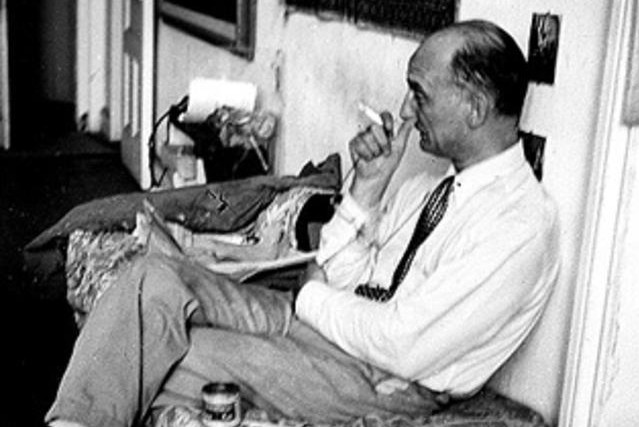

What is undeniable is this: At seven a.m. on the morning of June 21, 1957, a naked, sleep-deprived and bedraggled Emil Goldfus, a fifty-ish man, answered a persistent rapping on the door of his shabby room in the Hotel Latham on East 28th Street.

After about twenty minutes, the INS joined this impromptu breakfast klatch and took the subject into custody for violating immigration law. The Feds gathered up various bits of evidence that were strewn about the one-room lodging, including identification cards listing his name as “Martin Collins” and “Emil Goldfus,” hollowed-out coins, shaving materials, cufflinks and pencils containing tiny, secret compartments, a shortwave transmitter, photos of other known agents and various devices for both creating and deciphering coded materiel.

More from Narratively: “How An Untested Amateur Blew Psychology Wide Open”

On August 7, 1957, my father, Burton Silverman—a young artist fresh out of the Army—was walking down the street on the way to his layout and graphic design job for the then-liberal New York Post when he caught a glimpse of a blaring headline at a newsstand: “RUSSIAN COLONEL IS INDICTED HERE AS TOP SPY IN U.S.” and the sub-header, “Suspect Said to Have Used Brooklyn Studio to Direct Network.” The lede further stated that he was, “The most important spy ever caught in the United States.”

For my father, it was a moment of extreme unreality. The face staring back at him from the newspaper was his good friend Emil, not some KGB spook. How could Emil be a “master spy,” or even a common, everyday spy? He was an amateur painter, a fine guitar player and a charming older gentleman. How could that man be the enemy? He was frozen in his tracks, transfixed by the image, unable to reconcile the contradiction of the man he knew (or thought he knew) with the words in print staring back at him. It was as if a hole in the fabric of his universe had suddenly opened up under his feet.

* * *

So yes, a spy. In New York City. In Brooklyn. Emil Goldfus wasn’t a daring man of mystery, furtive and dripping with enigmatic sexuality, draped in a leather trench coat, a cigarette dangling from his lips, being pursued by a tuxedoed hybrid of James Bond and Jason Bourne. He was a balding, middle-aged man with a wiry build and a sharp bony profile, who seemed to wear nothing but gray. Okay, so he did have a trench coat—or at least a bulky raincoat.

Burt Silverman met Emil Goldfus in the winter of 1954, in the elevator at Ovington Studios, a building where he and many of his friends and professional colleagues rented space on Fulton Street in Downtown Brooklyn. “I was just out of the Army at the conclusion of the Korean War,” Silverman says. “I got a space in the possibly last artist-only studio in the city, and I often slept there because I still couldn’t afford my own place and was commuting from my childhood home.”

There stood a courtly, oddly dignified stranger, in baggy pants, a rumpled raincoat and a floppy, oddly casual hat. There was a brief exchange of mumbled hellos and, even though they exited on the same floor, nothing else was said.

“He had this accent,” Silverman explained. “You just couldn’t place it. There was a strange, rolling ‘r’ sound when he said my name—Burrrrrt—as if he had a Scottish burr, though he explained it with a story about an aunt from Scotland that had raised him.”

A few weeks later, Silverman was working late at night when Goldfus knocked at his door and asked to borrow a cup of turpentine. They struck up a conversation, the older gentleman admiring the artwork he saw and referring to a nineteenth-century Russian landscape painter Silverman had never heard of named Isaac Levitan.

Over the next few months, a friendship began to form. Though Silverman was the much younger man, he was the far more talented artist. Goldfus’s paintings were earnest, but amateurish. The younger man took on the role of teacher, instructing him on how to prepare canvases, what brushes to use, the basics of color theory and how to render the human form.

Goldfus also—slowly, guardedly—shared a few bare-bones details about his life: how he’d been a student in Boston, but had traveled around the country working as an accountant, then as an electrical engineer and finally as a photo finisher, though he’d also spent some time in Pacific Northwest lumber camps. He played the guitar brilliantly (for an amateur), and made a concoction called “jungle coffee” by boiling the grounds directly in milk on the stove.

He was also a frequent visitor to Silverman’s studio, accruing a vast amount of knowledge just by spending time with him and watching him paint, saying nothing.

“Now, it’s a relatively normal thing for me to do to allow someone around while I work,” Silverman adds. “But Emil’s the first person that I ever did that with, and what it taught me was that two people could provide some kind of comfort, some kind of ease, but without speaking. Just existing.”

Emil Goldfus also became a part of the larger group of artists who rented space in the studio, including the famed caricaturist David Levine; the cartoonist, playwright and author, Jules Feiffer; Sheldon Fink; Danny Schwartz; and Harvey Dinnerstein, all of whom would go on to achieve success in the art world.

The men struggled with the realities of the ’50s art world: the celebration of Abstract Expressionism as expressed by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and others of their ilk, the overt hostility to the representational work that they all favored and the idea that what they were doing wasn’t “real” art or could be dismissed as mere “illustrations.”

More from Narratively: “The True Story of the Kids from ‘Kids'”

They’d talk late into the night, arguing about their shared aesthetic concerns and the politics of the era. As a whole, these angry young men veered sharply to the left, especially within the context of the stultifying, downright paranoid atmosphere that was Joe McCarthy’s America. Some of them had in the past been members of the Communist Party USA, the largest, most influential Marxist-Leninist political party at the time.

“It’s difficult to imagine it now, but even if it never changed what we said and how we said it, there was always the nagging thought in the back of our heads that someone was listening; that we’d lose work or jobs,” says Silverman. “It was so easy to slip into self-censorship.”

Goldfus’s politics were quieter. He certainly didn’t disagree with the howls of protest about the with-us-or-against-us mentality, or the group’s belief that the all-powerful, all-pervasive, creeping Communist menace within our midst was a red herring (pun intended)—an excuse to stamp out thinking or behavior that was at odds with Coolidge’s dictum that “The business of America is business.” They were enraged by the wiretaps, committee hearings and trampling of the First Amendment, and saw them as part of a slippery slope towards Fascism.

Mainly, he sat on the periphery of the conversations, as one might expect of an older, wiser man, amused by the fiery convictions and enflamed sensibilities of youth, his ardor tempered by a certain degree of cynicism and the realities of life. He was practical, not an ideologue in any sense of the word. It’s certainly possible that his true sensibilities were kept under wraps so as not to arouse suspicion amongst the group. One story that might lend credence to that idea occurred when Silverman and Goldfus were once again in the studio late at night. They were in Goldfus’s room and his shortwave radio was on, sputtering an unfamiliar, Strauss-like tune along with an indecipherable, Central European-sounding commentator.

The phone rang in Silverman’s studio. He answered it, and the voice on the other end asked why he was working at such a late hour. Jokingly, Silverman responded, “Oh, Emil and I were just listening in on Moscow.”

When Silverman hung up the phone, Goldfus’s affable, easygoing demeanor had vanished completely, replaced by a cold, hard glare—the only one he had ever evinced in the three years they were friends. He snapped, “Don’t ever say such a thing like that on the telephone again. Not even in jest.”

Goldfus wasn’t wrong. Conspiracy charges have been built on far flimsier evidence than ill-considered jokes, especially via telephone. It’s the kind of incident that, under normal circumstances, wouldn’t be memorable. It’s only in recollection, when you discover that your friend was a spy, that it stands out.

There were other odd moments as well: nagging details and incidents that just didn’t make sense. To Silverman, Jules Feiffer said, “You know, Emil gives me the feeling of a guy who’s been on the bum. No matter how much of a fat cat they get to be, they never lose that look.”

Danny Schwartz agreed. Upon first meeting Emil Goldfus and hearing his story about working as a photofinisher, he said that Goldfus was too worldly and too educated for that particular trade, saying, “You know, the whole thing sounds fishy. This guy isn’t what Burt [Silverman] takes him to be.”

Silverman’s brother Gordon had his suspicions as well. He was an electronics engineer, and one day, while visiting Silverman’s studio, he got into a conversation about physics with Goldfus, finding that he possessed a degree of expertise that was surprising for someone that wasn’t a professional.

Of course, when he wasn’t in his studio, Goldfus was, in fact, engaged in espionage.

* * *

The man my father knew as Emil Goldfus was actually born Vilyam “Willie” Genrikhovich Fisher to Russian émigré parents in the United Kingdom. He returned to the Soviet Union in the 1920s, served in military intelligence in a variety of functions, joined the KGB after World War II, and was eventually sent to the United States as a mole.

At this point, the facts of what Goldfus may have done become a tad murkier, mainly due to the fact that the information available comes from both U.S. and Soviet government sources, all of whom had an interest in presenting Goldfus as a master spy. To clarify, there’s zero doubt that Goldfus was engaged in espionage. What’s in question is the headline on the front of the paper that Silverman saw: TOP SPY.

Under yet another false name—Andrew Kayotis—he arrived in New Mexico in 1949. Though the exact nature of his activities at this time remains unknown, biographies of Goldfus have stated that there are indications that he was there to assist with the process of transferring information relating to the Manhattan Project. By 1950 he was in New York City, establishing his identity as Emil Goldfus. For the most part, this simply meant going to the same store to buy the same brand of cigarettes and having a passing encounter with the shopkeeper. During this time period, using the name “Milton” and affecting an English accent, he made contact with Lona and Morris Cohen, both of whom associated with Helen and Morton Sobell, later co-defendants along with Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

In the summer of 1954, going by the alias “MARK,” Goldfus had his first meeting with his new assistant, Reyno Hayhanen, code name “VIK,” living under the alias Eugene Nikolai Maki. Hayhanen was a miserable, incompetent drunk, living with an angry, equally drunk young wife in Peekskill, N.Y.

Goldfus would receive coded messages from Moscow via his shortwave radio transmitter. He would then translate the code via his Russian codebook into yet another code, and then make microdotted messages, photographing, shrinking and transferring those messages to the secret compartments that he had hidden inside the laundry list of everyday items that the F.B.I. discovered: the coin, the hairbrush, etc.

The vast bulk of his time was spent in this delicate, precise, ritualistic and yet ultimately tedious task. For the most part, these messages were mundane: letters from home, records of cash deliveries, changes in the times for processing and sending other orders.

Here’s a translation of microdotted messages that were left for Hayhanen by Goldfus, according to the F.B.I.’s file on the case. There are probably more sensitive, national security-type messages that aren’t freely available online, but those we can access read like inter-office memos.

1. WE CONGRATULATE YOU ON A SAFE ARRIVAL. WE CONFIRM THE RECEIPT OF YOUR LETTER TO THE ADDRESS `V REPEAT V’ AND THE READING OF LETTER NUMBER 1.

2. FOR ORGANIZATION OF COVER, WE GAVE INSTRUCTIONS TO TRANSMIT TO YOU THREE THOUSAND IN LOCAL (CURRENCY). CONSULT WITH US PRIOR TO INVESTING IT IN ANY KIND OF BUSINESS, ADVISING THE CHARACTER OF THIS BUSINESS.

3. ACCORDING TO YOUR REQUEST, WE WILL TRANSMIT THE FORMULA FOR THE PREPARATION OF SOFT FILM AND NEWS SEPARATELY, TOGETHER WITH (YOUR) MOTHER’S LETTER.

4. IT IS TOO EARLY TO SEND YOU THE GAMMAS. ENCIPHER SHORT LETTERS, BUT THE LONGER ONES MAKE WITH INSERTIONS. ALL THE DATA ABOUT YOURSELF, PLACE OF WORK, ADDRESS, ETC., MUST NOT BE TRANSMITTED IN ONE CIPHER MESSAGE. TRANSMIT INSERTIONS SEPARATELY.

5. THE PACKAGE WAS DELIVERED TO YOUR WIFE PERSONALLY. EVERYTHING IS ALL RIGHT WITH THE FAMILY. WE WISH YOU SUCCESS. GREETINGS FROM THE COMRADES. NUMBER 1, 3RD OF DECEMBER.

The microdotted messages would be left at “dead drops.” (Concealed spots for messages where the aforementioned items could be surreptitiously left behind, until such time as another agent could receive them.) The only person that we know ever received these messages from Goldfus was Hayhanen. It’s certainly possible that there were others. The F.B.I alleges that Goldfus was in charge of a ring of spies, a massive network of agents. If that’s so, we have never learned the identity of these co-conspirators.

With Hayhanen, Goldfus set up three locations for dead drops in the city: One was in the Bronx—literally in a hole in the wall on Jerome Avenue near 165th Street—another was on a bridge in Central Park near Tavern on the Green, and a third was in the balcony of Symphony Space, the performing arts center on the Upper West Side. He also had other locations set up as signal areas, for determining if he had received a message, for notifying others that a message was ready for pickup, and for when a face-to-face meeting was necessary.

This was his life. He would paint and hang out with Silverman and the others, and he would transcribe and deliver messages, then leave signals in blue chalk on signposts and other locations to indicate the presence of and/or receipt of said messages, as well as checking and rechecking all of these locations to assure that the system was properly functioning. There were no meetings with seductive femme fatales or intricate, high-tech acts of subterfuge. It was a job, like any other, filled with repetitive, often mindless tasks, and frustrations with co-workers and bosses alike.

* * *

In 1955, Goldfus told Silverman that he had a color-printing device that he wanted to try to sell and that he’d be going to California for a few months. In reality, he’d gone back to Moscow. According to Chester Hearn’s 2006 book, Spies & Espionage: A Directory, Goldfus was crumbling under the massive pressure of running the network and was frustrated by the lack of competence of both his underlings and his superiors.

When Goldfus returned a year later, he found the system he’d set in place was in complete disarray. If Goldfus was very, very careful, Hayhanen was the opposite. Messages in the dead drop spots had never been retrieved, radio transmissions had been sent on the wrong frequency, and the money he’d left with Hayhanen had been frittered away on prostitutes and his dependence on alcohol.

While Goldfus was in Moscow, Silverman had no idea what had happened to his friend. He had no way to contact him, knowing no other family members or individuals outside of the group at Ovington who might know anything about his whereabouts. He was on the verge of calling the police and filing a missing persons report when, one night in 1956, the phone rang and once again, he heard the sound of that distinctive burr intoning: “Hello Burrrrrrrrt.”

Goldfus explained that the trip to California hadn’t worked out, that he’d had a heart attack and ended up recuperating in Texas. Silverman asked why he hadn’t called, that they were worried sick, and Goldfus brushed it off by saying it wasn’t that big a deal, and that he didn’t want to put anyone out.

After his return from Moscow, Goldfus’s engagement with the group increased. The Ovington artists were planning a group show that was intended to be a rebuke to the prevailing tastes of the art world. Entitled “A Realist View,” they wanted to make a statement that was both political and aesthetic: that representational work was just as valid as abstract imagery.

Though he himself wouldn’t have any paintings in the show, Goldfus took part in the planning, suggesting strategy and discussing what work should be a part of the exhibition.

Silverman adds: “You could tell that he wanted to be a part of something and that he was excited. I don’t know if the trip to Moscow changed him, but it seemed like he cared less and less about the idea of being ‘undercover’ or maintaining a low profile. I think when he started painting he was rediscovering a life he never could have because he was a mole. Our show brought a bit of the old revolutionary fervor back, the idea that he was fighting the establishment. The reality of the Soviet Union destroyed whatever idealism he may have had, but this made it real again, even if it was a cover. Here was a man who was very, very careful, who had avoided detection for nine years. It didn’t deter him.”

* * *

In April 1957, Goldfus once again told his friends that he’d be leaving for a while, again crafting a false story as cover. This time, it was that he’d be taking a trip to Arizona to seek out a cure for his persistent sinus issues. In reality, he never left New York City; he just needed time away from the Ovington Studios to reorganize his network. Having grown completely disenchanted with Hayhanen and wanting him removed, Goldfus passed on Moscow’s order to Hayhanen to return to the U.S.S.R. Fearing for his life, Hayhanen instead turned himself in at the U.S. Embassy in Paris, where he quickly gave up the goods on his boss. Soon after, the F.B.I. was knocking on Goldfus’s hotel room door.

More from Narratively: “A Gay Male Escort Recalls His Craziest Client Request”

For Silverman and the other artists, the story they read in the newspapers didn’t make sense. If Goldfus wanted to establish a false identity in New York City, hanging out with a group of radical painters might have been the worst spot he could have picked. And spies weren’t supposed to form attachments, to make the kind of friends who’ll worry when you’re gone. If you want to be anonymous in New York, it’s a pretty easy thing to do. If Goldfus really were the ‘master spy,’ the man behind the iron curtain who the papers were eagerly exploiting, why would he risk making friends?

On the other hand, if Goldfus was a spy, and if he had been ordered to embed himself amongst a group of artists, wouldn’t that make them somehow complicit? If so, wasn’t that the greatest betrayal of all; that their entire ‘friendship’ had been part of a cover story?

They were petrified that they too were suspects. They were all interviewed by the F.B.I., and they inevitably went back over all the details of their time with Goldfus. Had it been a trap? Was Goldfus working for the F.B.I, the KGB, or both? What conversations had been recorded? They were sure that they were still being tailed, that the guy stopping to tie his shoe next to them while they made a call on a pay phone was concealing a recording device in his pocket.

That’s the thing about espionage. The daily grind may be boring, but it does elevate the mundane. Suddenly, there are no random occurrences, no coincidences. The woman with the stroller you see twice in the same day is following you. The odd clicks on your phone are a tap.

While being questioned, the Feds asked Silverman if Goldfus had ever borrowed anything from him—a typewriter, a guitar. Of course, the answer was yes, but suddenly you find yourself thinking: “Is there a secret compartment in the guitar?”

Silverman was puzzled as to why this information was vital, and what it could possibly have to do with the case, but the answer to any and all of his queries was: “I’m sorry, but all we can say is that this a matter of the highest national security.”

The phrase was enough to send a chill down Silverman’s spine. Though he was aware of the F.B.I.’s desire to validate both the massive “national security” apparatus and the concurrent presence of “the enemy,” he was also keenly aware that siding with Goldfus could have very dangerous, real-world consequences, whether he was guilty or not.

And then came the trial.

* * *

In October 1957, Silverman was subpoenaed by the prosecution to testify in the trial of Emil Goldfus.

Imagine standing in the corridor of the federal courthouse at Cadman Plaza, waiting to be called. You’ve had no contact with your friend since his arrest. You doubt the facts of the story but you also have to protect yourself. There’s no right answer. Whatever you say in that room will be a betrayal to someone or put yourself in harm’s way. You don’t even know what questions you will be asked or if this too is part of a scheme to entrap you in this web of spies. Most of all, you’re not sure if you’ll be able to look your friend in the eye.

Silverman’s time on the stand was brief. After a few preliminary questions by the prosecuting attorney—can you identify the defendant, how did you meet him, how long did you know him, etc.—he was asked to identify his typewriter, which Goldfus had borrowed and then evidently used in the process of crafting his coded messages.

That’s it.

No questions about his political beliefs, no insinuations that he’d somehow been involved with Goldfus’s espionage, just a typewriter.

Silverman answered, “Well, it looks like my Remington Portable, but there are thousands of them out there. I can’t say for sure.”

Goldfus’s lawyer asked Silverman about Goldfus and his integrity—was he kind, generous and honest? It was possibly a foolish decision, but Silverman said that his reputation for honesty was “beyond reproach” and that he’d never heard a negative thing said about him.

As he was leaving the stand, he caught Goldfus’s eye. A smile seemed to curl around the edges of his mouth and he nodded. “He looked at me—and I remember it very specifically—I felt like he was saying ‘It’s okay,’ that he understood, and that he forgave me.”

* * *

Emil Goldfus was convicted of conspiracy to obtain and transmit U.S. defense information, and of acting as an agent of a foreign government. He was sentenced to thirty years in prison and a $3,000 fine, even though the prosecution had failed to identify any other members of the ‘ring’ that he allegedly operated. While in federal prison in Atlanta, Goldfus’s lawyer contacted Silverman, asking if he’d be willing to correspond with his client.

Silverman refused, explaining that, as much as he’d like to, the political climate of the Cold War made that impossible. In 1962, after only serving four years of his sentence, Goldfus was sent back to the Soviet Union, traded for downed U-2 Pilot Gary Powers in a truly filmic exchange on the Glienicke Bridge, known during the Cold War as the “Bridge of Spies” for the numerous transactions that occurred there.

After his return, the U.S.S.R. feted him as a national hero—an operative who had evaded and subverted the Americans for nine years without detection. Though like the F.B.I., the Soviets never overtly declared what information Goldfus had obtained and sent back to Moscow, they were just as invested as the United States in the myth that Goldfus had been a “master spy.”

For both sides in the Cold War, there was value in inflating Goldfus’s importance. That’s not to say that there wasn’t actual espionage occurring, both on Goldfus’s part and by others—there was. But in order to justify a perpetually increasing defense budget—the Military-industrial complex that Eisenhower warned against—from time to time, you need to actually produce “the enemy,” and so Goldfus’s head was triumphantly mounted on the wall.

Three years later, in 1965, Silverman met a writer named Louise Bernikow who wanted to write a book about the alleged master spy. They spent a year and a half researching the story, hoping to get permission from the Soviet Ministry of Culture to visit Moscow for an interview with Goldfus. In 1967, they got their wish. Silverman describes Moscow as such:

“The center of the city seemed vast. Crossing the street was an adventure, because they must have been at least fifty percent wider than Fifth or Madison Avenue. The buildings seemed heavy and overbearing, and even during a snow-free October, the prevailing colors were grey and brown. I remembered that Emil always had that combination of colors in his clothing and in his work; in his art he managed to find a way to bring a bit of Moscow with him.”

“The balcony of the Kremlin—probably three or four stories high—overlooked a cobble-strewn area that must have been the equivalent of about five football fields. Perched up there, the arena packed with thousands of subservient but still wildly cheering ‘admirers,’ everyone from Nicholas Romanoff to the Commissars would feel invulnerable and impervious to change or the march of history. It felt permanent and impenetrable in a way that still sticks in my mind.”

Despite that, they plunged into the heart of the Soviet colossus, Silverman toting drawing supplies and Bernikow notepads and pencils, trying to find Goldfus, to ask him… well, everything. Why he’d gone “undercover” in the worst situation a spy could possibly conceive, what had happened to him since he was sent back to the Soviet Union, and maybe just to give Burt Silverman a chance to end his friendship in a manner that wasn’t irrevocably skewed by massive, international, geopolitical stakes.

“Suddenly, I was thrust into a curious role, that of a pretend ‘arts editor’ delving into the bureaucratic bizarro-world that was the Novisti,” Silverman describes, using the name of the Soviet news bureau. “Surrounded by genuinely scary, overeager party hacks that may or may not have seen our arrival and desire to talk to Goldfus as an opportunity to strike a blow against the ‘degenerate’ United States.”

“1967 was the fiftieth anniversary of the revolution and the Politburo was not disposed to a sensational interview with their hero secret agent man. We felt—though we never really knew for sure—that we were being followed, that everything they said to us was a kind of double-speak or an attempt to determine our ‘true’ intentions.”

“I even devised a code that would indicate to someone back at [the publisher] that I might be in trouble,” Silverman explained. Assuming that their calls and letters were tapped and were being studied for some form of covert activity, they instead devised a system in which Burt would send a telegram saying he was running out of a particular color of paint to indicate danger, “So Cadmium Yellow became my S.O.S.”

After arriving in Moscow, Silverman and Bernikow found that the interview with Goldfus had fallen through. Party officials said they had not been told anything about the pair’s official, journalistic visit.

“We were stonewalled, dead in the water, no hope,” says Silverman. “But The National Hotel where we stayed had the reputation—whether that was real or a misinformation campaign—of being a sort of auction house for rumors and secret agents from all over the continent. At the bar, we met a British businessman and we talked about why we were there.”

“We were put in touch with a man called Viktor Louis, a leaker of unofficial Soviet information (a standard part of all diplomacy) that went back and forth to Great Britain constantly,” Silverman explains. Of course, this was a false identity as well. He was born Vitaly Yevgenyevich Lui, worked as journalist with the Western media, and though he was not a declared member of the KGB, “Had a dacha; a summer residence that is usually reserved for upper-echelon party bureaucrats.”

Louis promised that he could arrange a meeting with Goldfus, but after a few days of sketchy cancellations and further promises, he called the hotel and demanded to know why they had leaked a story to the Herald Tribune. Evidently, the affable gentleman they met at the National Hotel happened to be a friend of an AP reporter.

Silverman tried to explain, but they were unable to assuage Louis’s fears that he was being set up, either by the Americans—with Silverman and Bernikow in the role of undercover CIA operatives—or by the KGB itself, with the two now placed in the unlikely role of double agents, trying to expose and entrap Viktor.

Louis ended the phone conversation on a cold, ambiguously ominous note, advising him to “take a vacation.”

Whether that was some kind of code or an implicit threat, Silverman couldn’t determine, but with all their leads gone, they ended their quest. Before departing, Silverman wrote a letter to Goldfus, saving a handwritten draft and sending the final copy to Goldfus. Whether he ever got to read it remains, like so much else, a mystery.

Here is the letter in its entirety.

“Dear Emil.

I am writing to you once again, this time from Moscow, and this time with almost no expectation that we can get together. (I hope you are aware that I have been trying to arrange a meeting with no success.) This trip was a gamble. I hoped that some minor miracle would take place. Perhaps this is a measure of my naïveté. I realize the enormous difficulty of such a reunion. As I said before, however, I’m sometimes pretty stubborn. There’s some ego involved as well. I couldn’t believe that friendship and human curiosity were not stronger than practicalities. But I see now that this was not even involved.

I have been in Moscow for ten days, and will probably leave this coming Thursday. Before going, and in the hope that this letter does get to you, I should like to tell you a few things more. First, about things long past: I’m sorry I didn’t write to you in Atlanta. In defense of that, I can only say that they were different times, and I was not above fear. I was also counseled by what I thought were wiser heads. Hindsight, and a changed political climate have made those decisions and that counsel seem excessively cautious or worse. Maybe the reason I’m here now is to make up for that.

The book about you will, I think, be a truthful and honest one. It will try to explain why you are remembered so clearly by many of the people you met. Certainly all my friends have that memory and think of you affectionately.

I hope that all of this will not cause you any difficulty. I must say that at some points in the last year and a half, I’ve thought of giving up the project, but always came back to it because it seemed more pertinent than ever.

It’s almost ten years to the day since your trial started back in Brooklyn. Many things have happened to all of us since then—to me, my friends Harvey and Dave, and to you as well. I had hoped to talk to you about all of it. I had also fantasized a trip we could have made to the Hermitage to talk about art and painting once again. I also thought we could talk about your feelings about America and the people you met there. Apparently, this is not to be. Some other time perhaps—when the two of us can meet simply as old friends.

I will not say good-bye, just au revoir.

Sincerely,

Burt Silverman

Colonel Rudolf Ivanovich Abel died of a heart attack in 1971, was given an official state funeral, and interred at the Donskoy Cemetery. In 1972, a Western journalist visited his grave, and saw the name “Willie Fisher” had been added to the tombstone—the first time anyone outside of the Kremlin learned that “Abel” was an alias as well.

***

“I wrote in Bernikow’s book (and I still believe this) that he was the enemy, but he was my friend,” says Silverman.

“In the ’80s, a guy from the BBC interviewed me about Emil, and asked, ‘How can you say he was your friend? He was in the KGB, sitting calmly in some windowless room and taking notes while people were being tortured? How could you not feel betrayed? How could you be a friend to that?’”

“I said, ‘You know what I feel betrayed about? When this government carries my flag into the cauldron of dictatorships in South America; when Kissinger is involved with the death squads in Honduras—that’s what I call a betrayal.’ The journalist didn’t transcribe that part.”

“Emil’s spying produced enormous conflict. In the end, his greatest regret was that he’d betrayed the young men in Brooklyn. It wasn’t exploitative. In fact, it was the opposite. The friendships were a threat to his job, and of course to us. That’s the betrayal that haunted him—not to any country or government; to people, to us.”

It’s impossible to say for sure what led Emil Goldfus to embed himself amongst ex-Communists and radicals. In the end, that’s the mystery we’ll never be able to solve.

A cynic might say that it proves what a mastermind he really was; that by choosing to hide in a potentially dangerous place, he was engaging in a brilliant bit of misdirection. Hiding in plain sight, as it were.

A romantic might say that he was just tired of it all: the pointless, tedious, bureaucratic repetition of the job itself, the useless, incompetent co-workers, and the entire idea of countries being enemies. So, consciously or otherwise, he did the thing he really loved—painting pictures. That’s how Emil Goldfus remained true to himself in the midst of a life that was defined by deception; in which he was constantly playing a role.

Regardless of his motivations, for two and a half years, no matter what else he did in his spare time, the friendships he made, the work he did, and the life he led was real.

Yes, it was also a fiction but it was a fiction that was true in a way that the greater truth of espionage can’t alter. It was both real and a lie.

Somewhere beneath the infinite regression of all of these state-sanctioned masks lies Willie Fisher, also known as Martin Collins, and MARK, and Milton and Kayotis and Colonel Rudolf Abel of the KGB, but really just Emil Goldfus—the spy that was my father’s friend.

Narratively explores a different theme each week and publishes one story a day. More stories from “Unsolved Mysteries”: “Who Killed Heather Broadus?“, “The Sultan of Spatter”, “Grief Has No Deadline.”