This is what happened the morning I was to be arrested.

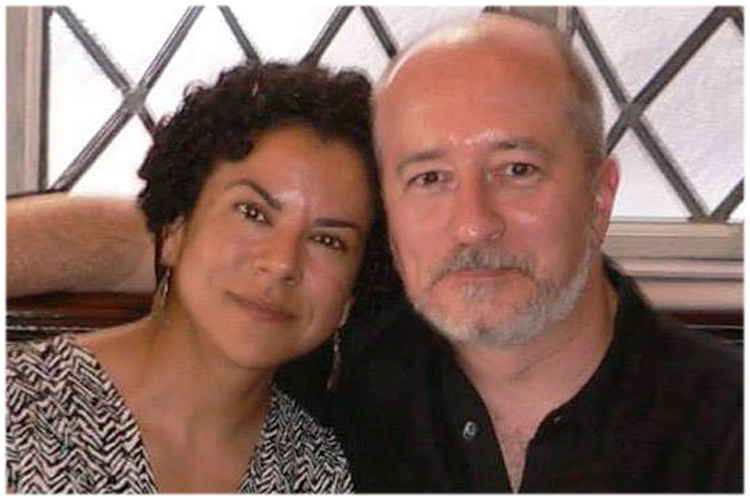

It was Monday, Feb. 11, 2008. I was in bed, under the comforter with my husband, John. His warm hand rested on my hip. The room-darkening shades blocked the sun. There was no light to signal it was morning, or that time had passed since I had gone to bed hours before and never slept. I spent the night hurtling toward the moment when I knew the phone would ring and change everything.

The comforter trapped my and John’s body heat. I was a furnace, fueled by anxiety. My tank, pants and the flannel sheets were damp. My heart pounded the firm surface of the mattress, and its rhythm felt irregular. The human heart may have a predetermined number of lifetime beats, and I was blazing through my quota. I thought I might die right there in my bed. That worried me least. Death was better than being revealed as a murderer.

I had murdered my child. Our long-anticipated baby boy, born beautiful and perfect, except he was born dead. He died inside my body where I’d nurtured him for almost nine months. He died in my womb, where babies are supposed to be safest of all, less than one month before he was supposed to emerge alive. The doctor wrote “stillbirth” on my chart, but my baby boy died because I failed him. There must have been a way to know, a sign I missed. Perhaps my baby had knocked or kicked in distress, but my negligence had killed him.

John is an attorney. I knew the different degrees of murder, and the role intentionality plays.

“Did he mean to do it?” I asked John about his clients.

It wouldn’t matter in my case. What mattered was that it happened. It happened in my body because I was a failure as a mother: I let my baby die.

I hadn’t asked John to re-explain the consideration of mitigating circumstances in criminal cases after we returned home from the hospital. I didn’t want him to become suspicious. Why would those things be on my mind just days after losing the baby? I thought it best he remain ignorant to maintain his innocence and spare him from punishment. If John knew the truth, he would see me for the monster I was. He would not defend me. He would be repulsed and abandon me. Who could blame him? I wanted to leave myself too, but I was trapped in my body, and that was my punishment: to always carry the scene of the crime with me.

The investigation had begun while I was still in the hospital. My doctor had examined my placenta after my tired, surrendered push to expel it. It was clotted. It had detached and denied my baby oxygen. I expelled clumps and clots of blood. Fragments could have lodged in my lungs, my heart, my brain. They should have killed me. How did I not know my body was harvesting and releasing these killers? Was it something I took? The years of birth control pills? The artificial hormones and fertility medications?

My doctor had collected the delivered items – ruptured placenta, blood clumps and clots, lifeless baby – to be dissected, analyzed and studied. He had said he would call Monday morning with the preliminary findings.

The phone rang. John and I both started. I inhaled and kept my eyes shut. John’s hand left my hip. The comforter and covers dragged across my body as he rolled away from me. He answered the phone as the second ring ended.

I knew by the way John spoke on the phone that he was learning the truth and knew what he had to do. I cried, but I would not resist being delivered to police custody. This was the reality inside my fractured mind on that Monday morning in February 2008. The trauma of stillbirth threatened to sentence me to a mindscape where I was not in control. As I prepared to be turned over to the police, I told myself I had no right to make a horrible situation worse. The best I could do was accept what lay before me.

* * *

The world stopped making sense five days before that morning. John and I had arrived to Hoboken University Medical Center before 6:30 p.m. on Thursday, Feb. 7, 2008. I was in labor and giddy. Within an hour, we were informed the fetal monitors detected no heartbeat. Our baby was dead inside my body. My doctor informed us an extraction could be performed via Caesarean section.

Extraction.

Objects offensive or harmful to the body are extracted. Our baby had been anticipated for more than five years. I chose to deliver the world’s most beautiful baby boy vaginally. He entered the world silently at 12:08 a.m., Friday, Feb. 8. John and I left the hospital 36 hours later with Liam’s death certificate.

The follow-up phone call from my doctor that Monday morning provided preliminary answers. I had been exposed to the strep A bacteria, different from the B strain that causes strep throat. The A strain attacks vital organs, is lethal to unborn babies, and often fatal to the mother. John took me straight to the hospital after my doctor’s call, not to police custody. Further tests and more antibiotics were administered to eliminate the risk to me. I also needed blood thinners for a previously undiagnosed clotting disorder. John and my family were relieved. I was safe.

I was terrified. Not by the lethal infection or the killer clots, but the real fear that I was responsible for the death of my baby. I had exposed my baby to a lethal virus. Maybe my hands were contaminated at the ATM, on the train, in the supermarket, and I did not wash them soon or well enough. Maybe there had been a tear in my skin, the tiniest scratch on a part of my body that may have come in contact with a shared surface at the gym, yoga studio, clothing store. What had I been thinking, being out and about in the world where anything could happen? I’d had so many tests done, before and after pregnancy. Was there one I had missed, a test that would have detected a predisposition or increased likelihood to developing blood clots?

My doctor’s Monday-morning call confirmed for me the lesson I learned in the maternity ward: Danger was in control, at all times, in any place. Danger knew it called the shots. It became a living presence that stalked me. It breathed the same air as I did. I panted all the time, like a dog that sensed distant thunder.

But I was not crazy.

I knew the precise time and details of everything that had happened: I awoke at 7 the morning of Thursday, Feb. 7. I took a nap at 1:30 p.m. and again at 4:45 p.m. I called my doctor at 5:57 p.m. John and I arrived to the hospital before 6:30 p.m. We received the news our baby was dead inside of me at 7:12 p.m. I delivered him at 12:08 a.m.

A crazy person wouldn’t be able to recount something so terrible in so orderly a fashion. I repeated the incantation to everyone: the doctors, the nurses, spiritual and mental experts. I believed that if I told them what happened, they could tell me the why. Everyone’s eyebrows raised. Their mouths formed Os, and took quick inhales, but there was never an aha moment. The doctors asked when I’d last felt the baby move. Had I noticed anything unusual? I had not. I hadn’t noticed anything at all. Maybe that was where I’d failed. The baby’s movements had kept me up the whole night before I went into the hospital. I was so relieved for a spell of quiet to nap that Thursday afternoon that I’d neglected the baby. The doctors took notes. I believed they were gathering evidence against me.

I was guilty, but I was not crazy. A crazy person wouldn’t have been aware that the things happening to her did not make sense.

“What a nice guy,” I thought when John brought me tea in bed during those postpartum days because I did not recognize he was my husband.

Leaving our condo unit became hazardous. I got lost in my own building. Outdoors, I couldn’t remember that red lights meant to stop at intersections. I became terrified of any change. I had seen what happened when logic and order were disrupted. I avoided sleep and lived in a constant state of high alert. No one understood that they could not help. Even the security measures at the hospital meant to foil baby snatchers had done nothing to stop death from stealing my baby. I gripped things – the arms of chairs, the bedsheets, my own arms – as tightly as I was gripped by constant terror.

In my life before the night at the hospital, I had been a writer. My mind had stored so many words, shiny and piled neatly. I lost my words the night I lost my baby. I stuttered and fumbled for the right word to identify a bowl, the right name to call my husband, or the right five-letter word to answer a standard clue in Monday’s New York Times crossword puzzle, the easiest day of the week. I had to develop a new language. I spoke about “when I was in the hospital” because my mind did not hold the word “stillbirth.”

I was aware that these episodes were out of the ordinary, but I couldn’t remember what was normal. I felt like I was always stranded at an intersection, unable to understand the signals that used to mean something to me. My mind had betrayed me. Just like my body had failed at its most basic tasks – making babies, becoming pregnant, sustaining pregnancies, keeping babies alive – my mind failed me too.

I didn’t tell anyone about my fears, especially not John. Maybe he would think I was crazy. He asked me to talk, but there was nothing I could say. Everything that had happened was too terrible for words. I was afraid to talk because it might break the seals on the silent things between us: that it was my fault Liam died. It was my fault we did not have children. A broken wife was too much work for no reward. I had no words to offer him for his hurt and pain.

I stuffed all the hurt – the events at the hospital, the funeral, the quiet of the nursery next to our bedroom – in a container, locked and tucked deep inside me. The container became heavy and bulged. The crazy things needed to be hidden there too, but the container could only hold so much. If it burst, it would break me.

* * *

By the end of February, I was sleep deprived and desperate. I needed professional help. I began seeing a woman I’ll call Dr. Berger twice a week for talk therapy. She did not turn me away.

“That is a terrible story,” she said when I called and explained why I needed therapy.

She cleared her schedule to see me the next day. She didn’t flinch at my desperation, the way other doctors and counselors had. Dr. Berger is a very assured woman. She wouldn’t bullshit me. I trusted her.

I used unspeakable words with Dr. Berger: stillbirth, funeral, autopsy, death. She was a professional and could do something with my words. I explained to Dr. Berger that things didn’t make sense. I told her about the episodes that occurred at home, intersections, everywhere. I was resistant to medication. Being altered scared me. In the hospital, I had been given pain killers. I had floated like a bubble and the world lost its sharp edges, but I felt slowed, too slow to react to danger.

Dr. Berger said there was a reason for my behavior. She held the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” before me, and pointed to the bold heading on page 526:

309.81 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

Was she kidding? Those words were for soldiers, victims of violence, survivors of devastation. I was none of those things. I was just one small messed-up woman who lost a baby.

Dr. Berger looked at me with more feeling than was characteristic for her. It was different than assuredness. It approached tenderness.

“Nancy, this is your war. This is your trauma.”

She reviewed the symptoms of PTSD with me. However, she didn’t realize the symptoms were not mine. I explained that they belonged to the other women.

Fire Woman was prone to outbursts of anger. She scared me. Fire Woman broke the kitchen cabinet door. She slammed it repeatedly until it came off the hinges because the predictability of the morning was broken when the newspaper had not arrived at its expected time.

The Breaking Woman had a thin voice that cracked when she spoke. She was afraid of everything. Her body frightened and disgusted her. She grabbed at the flaccid folds, and rubbed at her skin like it was covered with insects. The Breaking Woman couldn’t hear John’s gentle assertions of comfort over the pounding of her heart in her ears.

The Lost Woman showed up without notice at the worst times. It was because of her that I could not drive. When she took over behind the wheel, Kennedy Boulevard, a main artery in Jersey City, looked foreign. She couldn’t remember to take a left off the Boulevard onto St. Paul’s Avenue to get home. She couldn’t remember the purpose of traffic lights, that green means go and red means stop. She was like an extraterrestrial with no recollection of previous visits to earth. Every earth landing was baffling and new.

Gold Star Woman was methodical and detail-oriented, the same qualities that earned me success throughout my life. Ending life was a project, and Gold Star Woman approached it in very Nancy-like fashion. She knew to break down big jobs into manageable tasks and check off each one until the job was done right.

Gold Star Woman had a plan, too. She knew the route of the Summit Avenue bus, most importantly the stretch between Manhattan Avenue and Hoboken Avenue, five long blocks that included a downhill with the slightest curve. Gold Star Woman estimated that the morning driver, the one who accelerated at yellow lights, drove at least 30 miles per hour along that stretch. She knew the utility pole would obscure her from his view until she stepped out with a slight leap as if she was trying to dart across the street. She wanted to land in the exact middle of the bus’s flat front and be thrown, maybe into the path of oncoming traffic, but at least hard enough to shatter.

Who were all these women? Where did they come from? Dr. Berger assured me they were each one side or piece of me, just exaggerated to the extreme. I told Dr. Berger that there was a little tucked-away piece of me that was always aware, but not always in control. Each of the women felt so distinct. I felt like I lost touch with reality when one of them arrived.

“At those moments, when you dissociate, yes, you do lose touch with reality. It is a normal response to stress in your condition.”

In my condition.

I had to understand and accept that my condition was this: I had suffered trauma. The unexpected death of my baby in my body, the threat to my life, my helpless horror, all the experiences I had locked in the container – these were all mine. The events left no physical scars: Other than leftover pregnancy pounds, I looked like Nancy. But I was different.

I felt shattered because I was. The trauma was too big for one small woman to process. Dr. Berger explained that I survived by dissociating: I kept the trauma at a distance. The multiple Nancys were my army, each tasked to keep the pain away from me. This was my battle every day.

“But you bring yourself back to reality, to the present moment,” Dr. Berger said. “You’re aware, and are developing ways to bring yourself back.”

That was my fear, though: that there would come a point when I couldn’t bring myself back. There might not be a me to bring back. The episodes were happening more frequently. If Dr. Berger and the manual were correct and the women appeared in reaction to stressors that reminded me of the trauma, then just being alive was a trigger.

Our project, my work, was to collapse all those versions of myself back into one. I needed to strengthen the main Nancy. I had been on high alert since the night at the hospital, and operated only in survival mode. I needed to recognize the stressors that pushed my panic button and learn not to go into Code Red mode immediately. After almost six months of speaking with Dr. Berger, though, the episodes became more frequent, intense and longer in duration. I was about to cross the border into chronic PTSD. I needed to unlock the container and process everything hidden in there, but I was scared.

Dr. Berger recommended Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing therapy (EMDR). It sounded like it involved electrodes or being shocked. I said no immediately. Dr. Berger assured me it was physically non-invasive. It involved focusing on the disturbing traumatic images and memories while the opposite sides of the brain were repeatedly stimulated by sight or sound. Patients had shown dramatic improvement in less than 10 sessions. I was never the kind of person who believed such claims of fast results, but those initial months after losing Liam were not normal circumstances. I was desperate.

—-

I met the woman I’ll call Dr. Hill in her Upper West Side office for our initial consultation.

“Oh my God,” she repeated as I told her my story.

Her nasal exclamations frightened me. She was a professional, trained and experienced in dealing with trauma. She should have heard worse than what I told her. I was surprised Dr. Berger had not filled her in, but realized it was not as if my story had made the front page of any newspaper. That’s one of the harsh realities of trauma: It broke me, but life goes on. There is the slightest catch in the earth’s rotation when I relive the hurt, and it affects the gravitational pull, but only for me. I’m the only one who falls off the face of the world. I float alone in the distant atmosphere and see the planet, foreign, alien and indifferent in its spinning.

I told Dr. Hill the details of my story like I was telling someone else’s tale. I had to make myself “dead” and numb to the story to stay safe. Trauma, as both doctors explained to me, overwhelms the mind. I was in a constant state of fight-or-flight, and any stressor set off my hair-trigger response system. I had to recognize the trauma as my own so I could do the needed mourning, grieving and processing of the feelings, and move toward recovery.

A friend had told me it was necessary to walk through fire to deal with grief. There was no going around the flames. It would be painful, but it had to be done to get to the other side. I had to believe that I could walk through and survive. I had to trust that opening the container wouldn’t kill me.

* * *

My first EMDR session with Dr. Hill took place in her office. I had researched what to expect, and Dr. Hill went over the process again. I would focus on a disturbing image or memory from the night of the trauma while Dr. Hill engaged the opposite sides of my brain, no electrodes or shocks necessary. We decided on sound stimulation, in which I would wear headphones to listen to a consistent sound that switched between ears repeatedly. Apparently, this kind of stimulation distracts the brain enough that it switches off the fight-or-flight response. In theory, while my panic button was turned off, my brain wouldn’t know to be afraid when I entered the don’t-go-there place and unpacked the container. It would take a few sessions to train and assure my brain that I could encounter the scary stuff and remain alive.

Dr. Hill asked me to select a safe place. I used to balk at hippy-drippy, feel-good talk of happy, safe places. I used to think talk like that was for weak, broken people who needed to snap out of their issues. As the owner of my brain, I used to believe it was up to me to control and direct my mind. I had not sustained a traumatic blow to the head, or been on the battlefield and witnessed bloody carnage or loss of life. Yet there I was on Dr. Hill’s couch, holding a tissue box. My mind was a stranger to me. It had gone from an MP3 player to an old-school tape player that unspooled and chewed up cassettes.

I chose the safety of the coastal flats of Cape Cod Bay. Life on the flats followed an order: tide goes out, tide comes in. There were no surprises. With vocal directions and cues, Dr. Hill led me to the flats: I saw the ridged sand and felt the warmth of it below my feet. The breeze whispered on my cheeks, and I heard the calls of gulls feeding at narrow channels. She led me through every sensation so I could find my way to the flats immediately if I felt danger during the session.

Dr. Hill did not believe in baby steps. She wanted me to start right where it all happened: the delivery room. She used the same technique of questions and cues to lead me back to that Thursday night in February. I saw the white-tiled walls, the overhead lights, the head of my doctor, who was seated on a stool between my knees, and the head of the goose-necked lamp like a robotic assistant at his side. I hadn’t realized that I’d spent the time in the delivery room focused on the stark, blank white of the walls, not the chaos that would have been in my line of vision if I’d looked around me: my doctor’s face and its look of shock; the nurses’ faces, the one I heard crying, and the other who talked about a new father who’d fainted during his wife’s successful delivery in that same room; John’s face as he reassured me I was doing well in that same tone he used to distract me from gore or syringes. I heard it all, but saw none of it.

I had looked at the blank wall in the delivery room like I could disappear into it. I felt alone, even with John and a nurse each holding my hands, and my doctor directing me. They had sounded distant. My pressure dropped, my fever climbed, my blood flowed out of me. I was dying that night and it would happen to me alone, no matter how many people were around me.

I remembered clearly the animal fear and the shock of the pain of contractions. I’d never known physical pain that made me blind and arched me until I thought I would break in two. I understood the desperation of wanting to gnaw off my own limb to free myself. I had clenched the guard rail on the side of the bed between my molars. I didn’t care that drool dripped along my jaw and onto my neck like a senseless, disturbed patient. I was not right in the head at that moment.

I had bitten the fleshy part of my hand, hoping self-inflicted pain would counteract the pain that was breaking me. I bit down until I tasted blood. John had touched my face gently, his fingers near my mouth, as unafraid and trusting as the owner of a wild dog no one else goes near. He pulled my hand, and held it in his.

Danger and death had been in the delivery room that night. So much security – the guards in the lobby, the doors of the maternity ward that required a code, the cameras that monitored straight-a-ways and corners – but there was nowhere safe in that room. I had needed to hide. I found a crawl space in my mind, small and hidden, the most secret of undisclosed locations. I tucked myself into the space so that I was one compact ball. If I didn’t move, no one would know I was there. If no one knew, then I really wasn’t there. I was safe.

I had been present physically that night in the delivery room, but my mind, my self, was not there. I had pushed to deliver a baby I knew was dead. Each push brought me closer to a moment I’d wanted, but dreaded. It was impossible that someone, my own child, had died in my body. I had strained to expel the body from my own, and retreated further into myself.

I cried during that first EMDR session, but it was not because of the fear and anxiety that had plagued me for more than half a year. It was a delayed grief. I felt badly for that frightened woman who had endured that pain and anguish. I felt badly because she was me. The only way to survive that night in the delivery room had been to hide and not admit it was me.

“Things like this kill people. People don’t survive things like this,” I had thought that night.

Dr. Hill guided me out of the delivery room and onto Cape Cod with her voice, but it felt as if she held my hand and led me over uneven terrain from darkness to the flats. I took time to feel the warmth of the light, and the comfort of a familiar and beautiful place.

In my subsequent EMDR sessions, I found intense anger in the container. It was like a raging fire, its heat too intense to bear. It warped the casing. There was enough anger for everyone. There was rage at God for hurting, punishing and abandoning me. I was raised Catholic and sure that being angry at God doomed me to the eternal fires of hell. I was angry at myself for being so flawed. My body had proven to be a failure at conception and pregnancy. I was angry at all the wrong things people said.

“It wasn’t your time to be a mother.”

“You two aren’t so old. You can try again.”

There is no stillbirth etiquette or protocol to follow. Many people didn’t know what to say or do, so they chose to stay silent, avoid eye contact, or avoid me altogether. I felt some people had failed me. I was angry at feeling abandoned.

Each time I returned to Dr. Hill, she led me to the don’t-go-there place and each time, I unlocked the container. Those weren’t just memories in there: Those were real places and rooms to which I returned, like life scenes that had been put on pause. Each time I returned, I didn’t just watch; I stepped right back into the action. Put another way: Everything in the container was everything I’d distanced myself from. Before my EMDR treatment, stressors or reminders of that night hit the Play button so I was right back in it all. The memories all felt real because I had never let them play out in my mind. That was why the threat, like my fear and panic, remained real months after leaving the hospital. The things in there hurt, but they did not kill me.

I went to Dr. Hill for a total of four EMDR treatment sessions. I realized I didn’t need to return for more as I sat one day in Dr. Berger’s office. We both noticed the new strength with which I updated her on what I’d found in the container. They were terrible feelings and memories, and they were mine.

“I know it was me,” I told her, and we both knew I really did.

* * *

My post-trauma silence did not help me. Looking back, I realize part of my silence during those initial months was shock. What was there to say? The whole situation messed with my basic sense of order and reality: I had followed the steps to maintain a model pregnancy, so that beautiful baby boy should have been born alive. He should rest every night in the bedroom next to mine and John’s, not in Holy Name Cemetery. There will never be words to make sense of that.

It was humiliating to tell Dr. Berger about my episodes and the other Nancys. It’s humiliating to write this now. Only crazy people spoke of different selves, and I didn’t want to be crazy. Who would want someone so broken? Post-traumatic stress disorder explained my behavior, but also labeled and revealed me as defective. I couldn’t own that diagnosis, but the longer I denied it, the more it controlled me. Not talking about the trauma, the hurt and the crazy didn’t make any of it go away. It was hard and painful to connect my disordered feelings and actions to the loss of Liam. Six years later, I still don’t want to go there, but I don’t want to be imprisoned by punishing anxiety, guilt and anger. My freedom grows the less I hide.

Silence didn’t help me and John either. We didn’t share words, lost fluency in each other, and got caught in hurtful cycles. I was afraid he would leave me. A broken wife was too much work for no reward. The container was stuffed with my feelings and locked during those initial months because I had to stay numbed to stay safe. I rejected anything that threatened to make me feel. An invitation to talk or any physical touch felt like acid on my skin.

John had his own unspoken pains and struggles. He needed to be touched to be reassured, and felt rejected and alone by my distance. Silence cost us years of painful mistranslations of each other’s actions. We have achieved clearer conversations in the subsequent years. The truths revealed by the words we use are not always easy, but our misinterpretations based on what is not said hurt us more.

* * *

“I don’t know how she does it.”

People used to say that about the old Nancy, the original Gold Star Woman. No one knew I became something else after the stillbirth. I limited myself to a small number of familiar situations where people saw a few, smiling glimpses of me. No one needed to know how tender the insides of my cheeks were, raw because I clenched them between my molars to keep from crying. People were unsure how to offer help, and my pretending made it harder. It probably prevented some people from trying. I wasn’t the old Nancy, and had no idea how, or if I was able to do anything.

“Just breathe,” Dr. Berger still reminds me.

It is so simple. It was all I could handle in those initial weeks and months. Breathing was natural. Anyone could do it, even me.

I’m still a type-A, gold-star driven woman. That has not changed. Jokingly, I often refer to myself as Wonder Woman, but it’s no joke that I wish I was. I want superpowers that make me untouchable, able to outrun, leap over, and deflect pain. I’ve worked for five years to collapse all the Nancys into this one I am today, but I’m not invincible. I’m just one small, real-life woman, not guilty or crazy, just trying my best to live every day without punishing myself.