It is one of the most infamous episodes of “The Oprah Winfrey Show.” Guest Michelle Burford, a journalist for O Magazine, warned the studio audience, “Hold on to your underwear for this one.” Then she proceeded to describe a scary new phenomenon among young people: the rainbow party. “It’s a gathering where oral sex is performed,” she said. “And a rainbow comes from all of the girls put on lipstick and each one puts her mouth around the penis of the gentleman or gentlemen who are there to receive favors and makes a mark in a different place on the penis — hence, the term rainbow.” When Oprah asked whether such parties were common, Burford responded, “Among the 50 girls I talked to … this was pervasive.” What followed were countless hysterical television news reports on the supposed trend and and even a controversial novel by the name of “Rainbow Party.”

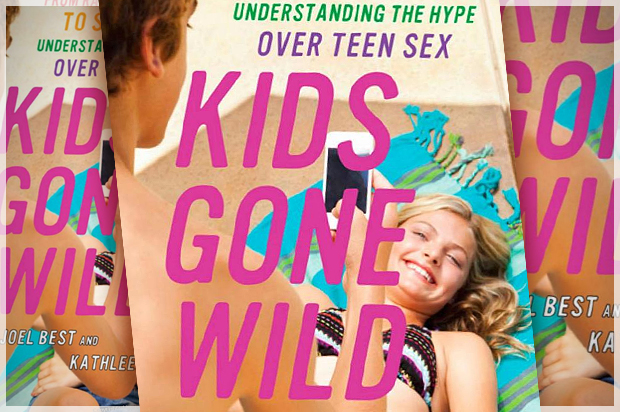

When it comes to concerns about kids these days, that might seem like an awfully dated reference. After all, we’ve long since moved on to fretting about the corrupting influence of Miley Cyrus’ twerking behind. But that just goes to show how quickly we cycle through panics about teens and sex. The new book “Kids Gone Wild,” by Joel Best and Kathleen A. Bogle, takes a deep dive into media coverage and online discussions surrounding three alleged phenomena that seized parental anxiety in the new millennium: rainbow parties, sex bracelets — color-coded jewelry that supposedly signaled the sexual acts one was open to — and sexting. The authors found scant evidence to support the existence of the first two. Of course, it’s possible that such things have taken place, but they were by no means common occurrences. Even teen sexting, which is undoubtedly real, has been blown out of proportion. The main takeaway of the book, which is more academic report than popular nonfiction read, is that these tales were driven not by fact but rather by a media willing to exploit parents’ worst fears for ratings and readership.

Salon spoke with Bogle by phone about fear-mongering television, parental anxiety and how kids are actually tamer than ever.

How did the rainbow party legend emerge?

What’s interesting is you would see the rainbow party legend emerge in North America, in Canada and the U.S., but then you see it pop up other places too. We’d see it pop up in Australia. We’d see it pop up in Great Britain. So it starts out one place but over time it tends to travel a bit. Now, rainbow party legend didn’t make it quite as far as the sex bracelet one. We found that interesting, how much further and how many more articles and hits there were on the sex bracelet story.

Why do you think that is?

Well, perhaps the rainbow party one sounded more preposterous to people than the sex bracelet one, because the sex bracelet one was this range of behavior. There were different versions of the sex bracelet story. There was the idea that you had to do whatever sex act corresponded with the color bracelet; then there was a version that said the colors you’re wearing signify what you want to do sexually or what you’ve already done sexually. But it seemed to be maybe more believable to people, this different range of behavior, than the rainbow party legend, which is basically an oral sex orgy story.

How did the rainbow party story first appear?

We saw it first show up in Meg Meeker’s book, “Epidemic: How Teen Sex Is Killing Our Kids,” where she talks about hearing about rainbow parties. Then from there you see it pop up other places and then it started to get a ton of attention when there was actually a fictional book that had that type of story in it. So the world of fiction and fact started to blend together where people were getting upset that it was in a fictional book and saying is this kind of book appropriate for teens, but also the idea that it was in there because that’s what’s going on among youth today. You saw the world of fact and fiction truly blend together.

There was the infamous “Oprah” episode. How influential was that?

I think what’s interesting is, we look at some of these anchors and news media people, they are an authority figure to the public; when they’re telling you something and presenting it to you as though they personally believe it, it affects what the public perception is. We have quotes in there where, for the sex bracelet story, Matt Lauer is giving commentary saying he’s locking up his daughter until she’s 20-something because of the stuff that’s going on with kids today. We have a quote from Montel Williams where he references the sex bracelet story and someone in his audience says, “I don’t think that’s going on where I live,” and he responds, “That’s a lie!”

With Oprah, because that reaches so many millions of people, particularly women and women that have children, they’re hearing that story and saying, “Oh my god, did you hear on Oprah what’s going on?” We even have a quote in the book that looks at another reporter when they’re looking at issues of youth and sex, a reporter by the name of Costello, that says, “It must be true, didn’t you see that Oprah episode?” So even another reporter ends up citing Oprah as a fact-checker on rainbow parties being real.

Did you find any evidence to suggest that rainbow parties were real?

We didn’t find any evidence that they’re real, but one of the things we try to point out in the book is that urban legend became this term over time where people say, “If it’s an urban legend, it never happened.” That wasn’t the origin of the term. The origin of the term was about how the story spreads and gets exaggerated and morphs over time. It’s impossible for us to prove a negative. We can’t prove, we don’t have hidden cameras in every basement in America, so we can’t prove that it didn’t happen. We can only say that these stories have all the tell-tale signs of urban legend. For instance, commonly for urban legends, people will say, “Well, I haven’t done it, but I have a friend of a friend who has.”

Another interesting thing that we caught happening in newspapers is someone would say, “Well, it’s not going on here in Pittsburgh, but where it’s really happening is on the West Coast,” or someone in the South writes in to the local paper saying, “This rumor is baseless here. This whole sex bracelet thing, people just wear those bracelets for fashion. Where it’s true is up in the Northeast.” There’s this idea that it’s not happening here but they know that it’s happening elsewhere. That’s even true country to country.

How did the sex bracelet story emerge?

We first started to see Time magazine and some outlets like that pick it up. Then it started to spread like wildfire. It got picked up by the Associated Press. What was interesting about it was that some of the newspaper stories did pick it up and talk about it as a possible urban legend. They didn’t just say “this is real.” But then when other venues would cover the story, including television media, they didn’t necessarily include that urban legend idea. So even though they could have easily Googled and seen an Associated Press or Washington Post story and said, “OK, they’re saying this might not be true, that this might be a legend, or that this might be greatly exaggerated,” it would still get picked up as, “This is happening, this is real.” And because there really were schools that were banning the bracelets, there was something true that the media could cover. But banning the bracelets is not the same as having evidence that this is a widespread practice among youth.

Right, who’s to say that the schools aren’t just reacting to the media coverage?

Right. They all end up feeding into each other, sort of a chicken and egg problem.

Did you find any firsthand stories of adolescents who participated in a “sex bracelet” game?

What we do in Chapter 4 of the book is we look at some of the discussion threads and things on the Internet. We end up dividing it into whether it’s a first-person account or whether they’re saying it’s a friend of a friend or whether they believe the story or whether they’re a doubting Thomas. There are people in those discussion threads that say they know it’s true, trust them, they’ve been to the rainbow parties themselves. To the extent that people want to take that as evidence of it happening, which I think a lot of people would be doubtful of, there are those accounts. But we thought that was interesting in and of itself. Urban legend used to be the world of rumor and whisper down the lane and difficult to trace; we were able to because so many newspapers are indexed now, and because there are these discussion threads online, we were able to trace the reaction to it.

When it comes to teen sexting, it seems there’s a lot more actual evidence.

Yeah, it’s true that teen sexting is real and that it’s happening, but some of the questions we raise are that, first of all, it was thrown out there that this is happening among 20 percent of teens, but when you looked a little bit deeper at that number, that included people who were over age 18 where it’s not illegal; that number also was not based on a representative study. That raises questions about whether that number was correct or not, and later studies that were representative had a much lower number. So how widespread it is is the question.

The other issue that’s probably more important than how widespread it it is looking at when sexting is happening what is really going on. A couple of researchers at University of New Hampshire looked at it and found that most often it was people who were in some form of a romantic relationship sending a provocative picture to their significant other. They questioned whether such a thing should be criminalized at all; after all, it’s not illegal for two 17-year-olds to have sex. So should it be illegal to send a topless photo to the other? Should you register them as a sex offender and talk about lifetime consequences for doing that. On the other hand, they divide into a second category what they call aggravated incidents, where sexting is then maliciously forwarded to large numbers of people. To me, that’s worth our society considering how we can criminalize that. But that, to me, isn’t just about youth sexual behavior, it’s about violations of privacy.

Part of what we’re raising by tying the different stories together is when the sexting story hit and when people started to react to it they were reacting to the story based on the belief that kids today have gone wild. If you believe to start with that kids today are out of control, they’re having sex like no generation before, they’re doing all these wild things, and then sexting happens, then you might say, “Well, we’ve got to crack down on it.” If you actually knew the data, which we show in one chapter, that there are fewer high school students sexually active than there were in the early 1990s, for example, and that kids today have not gone particularly wild as the media has portrayed, and then if you look at the sexting issue you might see it in a very different way than when you see it through the lens of the hype that’s gone on.

Are parents more concerned today about teens and sex than they were a few decades ago?

Well, I think that we try to add some historical context and say in previous generations they were worried about going steady, they were worried about lipstick, they were worried about miniskirts, they were worried about rock music. It’s not new for parents to worry about kids or that their pop culture interests or their access to the opposite sex is going to lead to trouble. We’ve been worried about that for a long time, but we also hear stuff today about “worst than ever” and “what these kids today have to face.” Because the culture doesn’t censor the way it once did and there’s more stuff out there that includes sexual content, the idea was teens are going to go that way too. They’re going to follow the lead. We didn’t really find evidence that fits that mold. Because, like I said, there are trends that are even slightly more conservative than they were 20 years ago. In general a lot of behavior is fairly constant over time.

Why is there such a fascination with these stories about kids gone wild?

I think one of the things we show in the last chapter is it’s not just one group that likes the stories. Kids themselves like them because it’s great gossip. What’s better than to say, oh the girl wearing a red bracelet you know what she does, she gives lap dances. They make stories teens like to pass around that make interesting gossip. Parents are always worried about their kids, of course, and they’ve been fed a lot of media stories that feed into that. So the idea that their child who they think of as innocent might be corrupted by these other forces, that feeds into something that they’ve been fed and believed for a long time. Schools want to show how they have things under control, they know what’s going on and they can talk to parents about it. So they can say, “We banned those bracelets to put a stop to that.” Then, of course, the media; there’s both the idea that sex sells but also fear sells. Saying listen to this story, you have something to worry about. You have to listen to this because you don’t know what’s really going on and it could affect your child. That’s what gets viewers, and television producers and newspaper columnists are aware of that.

What’s a more recent example of a “kids gone wild” story?

In the preface we talk about the Miley Cyrus thing as a really recent example of how a story gets passed around the world showing the cultural fear that kids have changed.

Twerking, you mean?

If you look at the preface and look at the headlines that were around the globe within a matter of days just feeding into that idea that, oh, how did Hannah Montana turn into this sexual object? Feeds right into this fear that people have that kids are going to be corrupted. Another thing that’s interesting is when you look at a few decades ago and parental fears, you often saw fear from the outside, like pedophiles or someone that could steal your kid. Now it seems like the fear is the kids themselves, that the kids themselves are going to corrupt one another or lure your kid into going to a rainbow party or trick your kid into sexting. So it’s interesting that that fear has shifted. Not that we don’t still have the pedophile fear, but that the fear isn’t just of the outsider but the teens themselves.

Why the shift?

I think that because these stories all play off one another and because we started to hear them from so many sources, even though we chose the sex bracelet and rainbow party stories, we could have as easily chosen the pregnancy pact story or some of the other stories that have gone around. When things get so saturated with that message, one of the things I’ve noted when people ask me over the past couple years what research I’m working on and I tell them I’m doing this book, it’s going to be called “Kids Gone Wild,” but it’s critiquing that idea and kids have actually not gone wild, or I even tell them what the stories are and that they’re urban legends, they for a minute kind of nod but then they say, “But kids today are really a problem …” It’s always the idea that kids today are worse than ever before.