Last week, the sitcom-watching portion of Asian America finally got the news they’d been waiting for with bated breath: Fresh Off the Boat survived.

Last week, the sitcom-watching portion of Asian America finally got the news they’d been waiting for with bated breath: Fresh Off the Boat survived.

In fact, a lot of great shows survived, including shows whose survival was seen as a kind of referendum on TV diversity: Blackish, Jane the Virgin, andEmpire, as well as the whole Shonda Rhimes juggernaut (Scandal, How to Get Away with Murder and Grey’s Anatomy). But Fresh Off the Boat held a special significance.

The second ever Asian-American family sitcom in TV history will not share the fate of the first ever Asian-American family sitcom in TV history, Margaret Cho’s All-American Girl—an ignominious ratings slide followed by a peremptory cancellation after one season. We’ll get to see the fictional Eddie Huang continue to court his neighbor Nicole, watch what happens when he turns 12, and see what develops in the rivalry between Louis Huang’s Cattlemen’s Ranch restaurant and his arch-rival chain the Golden Saddle, etc.

Moreover, unlike All-American Girl, Fresh Off the Boat isn’t a single anomalous network “experiment” that will define the fate of Asian-American representation in media for a generation. Coming on the heels of Fresh Off the Boat’s renewal is the pickup of Ken Jeong’s Dr. Ken, the third Asian-American family sitcom in TV history, which promises to be as different from Fresh Off the Boat as, well, Ken Jeong is from Eddie Huang. (Using a very loose analogy, the second-generation professional-class Dr. Ken is to the striving immigrant entrepreneur Huang family as Cliff Huxtable was to the Jeffersons. Two very different shows about two very different experiences.)

It’s a good time for minorities looking to see themselves on TV. The only Asian-American I know who probably isn’t feeling good about this is… Fresh Off the Boat’s ostensible creator, the real-life Eddie Huang. It hasn’t been a good month for Huang. It’s likely that he won’t be doing much with the show when it rolls around next season. And, I have to admit, that’s probably good.

It’s not easy for me to say this. I am a fan of Eddie Huang. I’ve even compared him to comedy legend Richard Pryor, a comparison I got in surprisingly little trouble for.

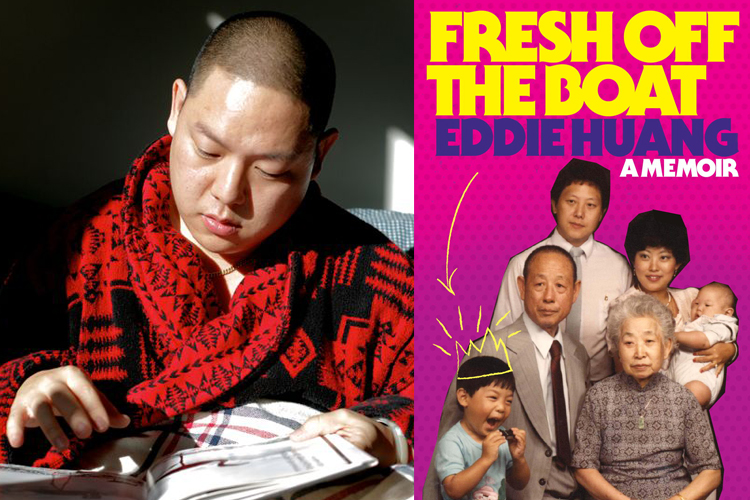

His original memoir Fresh Off the Boat was a breath of fresh air for me and many other Asian readers, in much the same way people say Pryor’s stand-up was in the 1970s—an explosive, unapologetic rejection of the respectability politics that weigh like an albatross around the neck of every person of color with a platform.

What I admired about Huang and even tried to imitate was the unfiltered rawness of his emotions—resentment, frustration and selfish arrogance all on full display, tossing aside the mask of humility our culture associates with “model minorities” in general and Asian-Americans especially.

You don’t realize how ingrained it is for our subculture to adopt unassuming modest deference as our default defensive pose until you see someone refusing to do it. To me, it always made sense that Huang would appropriate the language of hip-hop to give a voice to emotions he was denied as a child. Hip-hop is the language of suppressed emotion boiling over, a voice that embraces over-the-top violence, sexuality, aggression precisely because these are the things that respectability politics cowers in fear of.

I was with him when he casually described enduring beatings from his father, going to prison for brawling with fratboys, lusting after white girls with “pink nipples” as forbidden fruit, and still being angry enough about it all that he refuses to “rep America.” I was with him in standing by baring ugly things about his past and his present that all of us—but especially those of us pressured to be a “credit to our race”—don’t get to say. I can’t describe what a rush it was to see him, in print, kick aside the storybook redemptive ending of the immigrant’s tale and refuse to say “America is great.”

Because it isn’t great.

I’ve backed him up so much that it’s painful for me to have to peel away and say, okay, Eddie, you’re on your own. But increasingly, I’ve had to do that when I see his Twitter drama. Increasingly, I’ve had to remind myself that self-righteous anger without self-reflection is hollow, and not very liberating at all.

I’m biased, because I like the show and Eddie Huang clearly doesn’t. He’s tweeted about how he doesn’t watch it, how he feels it’s a dilution of his life story.

I respect that. I can’t imagine how I’d feel seeing bits and pieces of my own life manipulated to make “good TV.” I thought his initial Vulture op-ed describing his criticism of the show was an oasis of refreshing honesty in a desert of insincere TV hype. If he’d left it at the message of that op-ed – that he was conflicted emotionally about his own relationship to the show but still supported the show and its creators as its own, separate entity – then I’d be fine with it.

But to continue to slag off the show months after its premiere, based on the content of episodes he already knew about and even did voiceover work for, and essentially throwing everyone else working on the show under the bus—that’s not just unprofessional, it’s disingenuous. As others have pointed out, it’s not like Huang didn’t know he was making an ABC sitcom when he sold the rights to adapt his memoir. It’s not like Huang wasn’t handsomely paid for those rights, and it’s not like he doesn’t continue to profit from the visibility his association with the show gets him.

The more I think about it, the more a specific thing sticks in my craw: that Huang called out his friend Melvin Mar, a producer for Fresh Off the Boat, as an “Uncle Chan,” his version of the slur “Uncle Tom.”

It’s a big damn deal to use that name on a specific person, as opposed to using it to describe a behavior or class of people. It’s a way to throw shade not just on someone’s actions but their intentions, their integrity—to accuse them of willfully selling out their identity. And it’s hard for me to see how it’s fair to throw “Uncle Chan” at Mar, who gets paid to sell the show to his bosses and to the viewers, but say the epithet doesn’t apply to Huang for selling his rights to Mar in the first place. It feels almost like Huang is absolving himself of Uncle-Chan-ness by being the one to push the title onto others, casting the first stone.

That’s what started to turn me off, recognizing that cocky arrogance is an attitude that doesn’t just “punch up,” but once engaged, tends to punch in all directions.

The big news that landed Huang in hot water recently was his comment on Bill Maher’s show that he views Asian men as being in the same boat as black women, leading to a tweetstorm in which he becomes first defensive, then dismissive, then outright obnoxiously sexist to black feminist critics. (Any time you’re arguing with someone and end up sarcastically asking them out on a date, you’ve gone down the wrong conversational path.)

I won’t try to defend Huang’s actions in this matter. I’m glad he pre-emptively distanced himself from the show earlier so that the blowback from this incident won’t land on the people working on the show. But I will say I’m disappointed and confused that someone who turned a phrase that perfectly captured the in-between state of a model minority used as a weapon of anti-blackness in America – ”the dude who can cross the union line” – would cross the union line so readily.

Doesn’t he know that anyone who attends union meetings and brandishes their union membership card, who identifies with black oppression and uses the jargon and cadence of hip-hop to express themselves, had damn well better make sure they pay their union dues? That an Asian guy trying to ‘splain something to a black woman about race and gender better check himself as thoroughly as he’d expect of a white dude telling him about Chinese immigration?

That’s what I realized rubbed me the wrong way about Huang’s public persona: It’s one thing to be honest and raw about your own experiences. It’s another thing entirely to be that way about somebody else.

I look back at Eddie Huang’s epic takedown of Marcus Samuelsson in 2012 and I get the same bad taste in my mouth. I’ve never eaten at any of Samuelsson’s restaurants, but I get Huang’s anger at the way “foodie” versions of local cuisine turn restaurants into a beachhead for gentrification, I get the instant recoil when you see the media anointing a single figurehead as “one of the good ones,” I get how hard it is to keep your mouth shut when that instinctive reaction to inauthenticity kicks in.

But ultimately it’s an Asian guy telling a black guy that his restaurant isn’t black enough or Harlem enough. Even if you get your black friend (Harlemite and hip-hop producer Shiest Bubz) to back you up, it’s playing with fire.

I ultimately still agree Huang had the right to call out Samuelsson’s efforts to “class up” Harlem cuisine as condescending, but also think going so far as to call Samuelsson’s efforts to claim a black identity “admirable, heartbreaking and confused” was far more condescending. I don’t know how you could find fault with Samuelsson still being mad about it months later.

Maybe I’m being just as condescending to Eddie Huang right now. I don’t know. I do know that a frequent habit of cultural critics – one that I absolutely recognize and dislike in myself – is to be quick to criticize others as a defense against being criticized. It’s really hard for me not to read the assault on Samuelsson and Red Rooster as a pre-emptive strike against criticism of Huang for his own appropriation of hip-hop and blackness – proving his cred as someone who truly gets Harlem by calling out Samuelsson, a black man who lives in Harlem, for failing to do so.

Just like he defends the authenticity of his memoir by slamming the inauthenticity of anything in the show that deviates from it – not acknowledging that there’s things in the show that may ring more true for some Asian viewers than his memoir does because his experience is not universal, not acknowledging that showrunner Namchatka Khan, as a child of immigrants herself, might have as much useful input for a show like this as he does.

This brings me back to my own initial reaction to Huang’s overly facile comparison of Asian men in the dating scene to black women. Let’s agree for the sake of argument that, yes, cultural stereotyping means Asian guys are set up to “fail” at masculinity and black women are set up to “fail” at femininity.

Masculinity and femininity aren’t symmetrical concepts. You can’t call yourself a feminist if you don’t accept that. If the solution for Asian guys in the dating scene is to resist “emasculation” and reclaim their masculinity, you’re telling Asian guys to dominate, to take control, to take up space – and telling black women to be feminine is telling them the opposite.

If you stop your analysis at saying Asian guys and black girls get low marks on OKCupid because we stereotypically don’t fit gender roles very well, then your solution ends up being just to reinforce gender roles – Asian guys get told to be sleazy pickup artists and black girls get told to be Barbie. It’s a cure worse than the disease, and it’s an asymmetrical one, where women get the worse end of it.

I don’t think Eddie Huang buys the full-on misogyny that accompanies the narrative of equating Asian male oppression with “emasculation” – but he also doesn’t seem to appreciate how common and how dangerous that misogyny is. He steps into the swagger and arrogance and rage that he feels is his birthright denied him by white men who claimed it for themselves – without apparently asking if that outfit is a good look on anyone in the first place.

I know Huang has heard the Audre Lorde quote, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Another way to put it is that you can’t fight back against condescending tools by being one.

Huang’s memoirs and his other writings speak of a lifetime of struggling against being told things by assholes and tools. He’s pissed about a lifetime of privileged white dudes and their allies telling him where to go, what to do, who to be and how grateful he should be to be told. He’s pissed about this. So am I. That’s “model minority rage” in a nutshell, and it’s why the brand of the “Angry Asian Man” is so popular.

But to turn around and use that “angry Asian man” cachet to tell Asian women they should laugh off your nasty jokes about their appearance, or call black women “bums” for disagreeing with you? Or – even if you’re doing it in the name of racial equality – to openly and humiliatingly call out black men and other Asian men as less authentic than you because they made different choices than you made?

How is that any better? And more importantly, how is that any different?