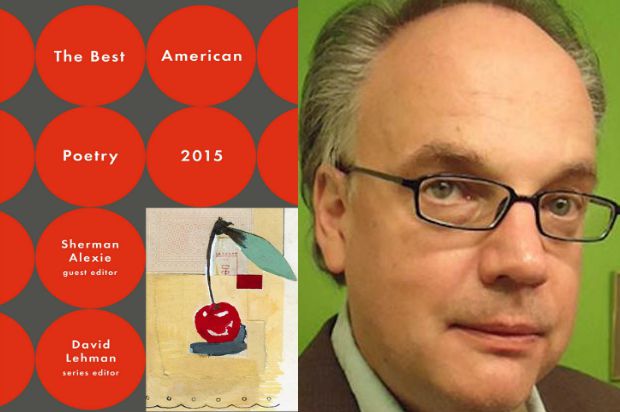

So all my Asian-American friends have been a-twitter (and a-Tumblr) about Yi-Fen Chou, neé Michael Derrick Hudson, the dude who got himself published in “The Best American Poetry 2015“ by submitting it under a pseudonym that presented himself as a Chinese-American woman (though whether he even knew he was using a feminine name is questionable).

Sherman Alexie, the Native American literary heavyweight guest editor who picked Hudson’s “The Bees, the Flowers, Jesus, Ancient Tigers, Poseidon, Adam and Eve” posted a complex sorry-not-sorry in response to the kerfuffle over Yi-Fen Chou’s self-outing as a white dude in poetic yellowface. I don’t fully agree with Alexie that disqualifying the poem over this deception would make him a hypocrite or turn his selection process, which he goes into in admirable detail, into pure identity politics. I also, like many snarky commentators who’ve weighed in on this subject, don’t think “The Bees, etc.” is a particularly good poem.

I also think, along with many of my fellow commentators, that Mr. Hudson, whose justification for the “extradiegetic” “persona” of the Yi-Fen Chou identity is that it helps get him published thanks to affirmative action, comes off as an asshole. And certainly, submitting a poem 40 times under one name, then continuing to submit it under a different name and getting accepted on the 49th try doesn’t prove anything, as many have pointed out. All it really shows is the writer’s cliché that you’re only likely to get an acceptance sometime after you’ve gotten enough rejections to want to give up.

Indeed, it’s telling how most of these anecdotal experiments in exploiting affirmative action don’t prove anything close to what the experimenters claim they do, like when Mindy Kahling’s brother claimed pretending to be black in his med school applications “worked” because he got a single, solitary acceptance to a mid-tier school. Meanwhile when we have the resources to do any large-scale, quasi-scientific study of how hiring managers look at big piles of résumés or prospective renters look at big lists of AirBNBs and it’s pretty clear that in the aggregate it’s easier to get stuff in this society if you’re white. (Which would make sense given that, you know, white people have more stuff in this society.) Even with Alexie making a conscious effort to give greater consideration to more marginalized voices he still ends up with a majority (60%) of white poets, more or less reaching parity with non-Hispanic white people’s actual prevalence in the population.

But other people have already gone over that stuff. I’d prefer to dive into something that hasn’t been talked about as much, the content of the poem itself, and how this whole mess reflects on that content.

The Stranger reviews “The Bees, etc.” as a poem that feels cynical about poetry. The New York Times’ David Orr pegs the poem’s voice as “Self-Satisfied Irony”. Both reviewers get that the speaker in the poem blabbing about “those blue flowers, the ones I can never remember the name of” is not supposed to be a likable guy, that the off-puttingly awkward phrasings like “that’s the very place Jesus wept” are intentionally off-putting.

But no one’s really commented on the rest of Hudson’s own author note, where he gives away much more in terms of “spoilers” about the poem’s meaning than he really should. He tells us that all of the science and history in his poem is intentionally “bungled or half-bungled.” The poem’s opening, where the speaker muses that engineers once thought it was scientifically impossible for bumblebees to fly, Hudson freely admits is a pure myth that snopes.com debunked years ago. “Ancient tigers” didn’t poop seeds from the Far East into the Colosseum–being carnivores, this would be unlikely–but some people think rhinos or giraffes might have. In the Greek myths Philomel was raped by her brother-in-law King Tereus, etc.

The speaker of this poem, in other words, is not that well educated. He doesn’t really know Greek mythology or the history of entomology, he half-remembers it. He’s also not that well-spoken–he blurts out awkward fragments like “atop yonder scraggly hillock.” He compares himself to an inept tour guide, his own language to “fractured, not-quite-there English.” He’s doing his best to have a rich inner life, an internal monologue worthy of transcribing into poetry, but he’s failing.

The speaker of “The Bees, etc.” is, in other words, basic. And he suffers from the basic dude’s core flaw of being intensely insecure about being basic and letting that make his otherwise forgivable basicness turn into something grating.

Note that the real Hudson is quick to “explain the joke” of his poem in his author’s note rather than have confidence that readers armed with Google will get that the factual errors are intentional. The speaker’s self-deprecation in the text isn’t enough for him–Hudson himself has to “extradiegetically” point out that even though he empathizes with this shallow dude who doesn’t read broadly enough or think deeply enough to have an interesting point of view, in real life he’s not that dude.

Psychoanalyzing someone you’ve never met based on their written work always carries a risk, but Hudson has, after all, put himself out there for such analysis by playing identity games to get into “Best American Poetry 2015,” so let’s look at his other work.

Here’s a poem that also invokes the Adam and Eve imagery from “The Bees, etc.” where Adam plays a puerile boor who thinks he understands evolution but clearly doesn’t really and can’t stop staring at Eve’s boobs long enough to realize the consequences of eating the apple. Here’s some more poems published under the Yi-Fen Chou name–one where the speaker is an obsolete relic, a cosmonaut from the old Space Race mocked and derided by the “incomprehensible 21st century” sci-fi nerds. One where, again, the imagery of obsolescence is invoked–the speaker’s heart as “fossil megafauna,” something big and clumsy and dying, and juxtaposed with a humiliating litany of boring, unfulfilling sexual encounters. Here’s one that’s straight-up entitled “Why I Never Amounted to Much: My Graduation From Ohio State.”

It’s not bad poetry. It’s not particularly memorable poetry either. It’s poetry that, as Orr observes, is fairly typical of the Self-Satisfied Irony brand of poetry–and in its typicality reinforces the insecurity that that ironic wall was erected to conceal.

It’s poetry by a guy who’s obsessed with the possibility that he is just an ordinary guy with nothing original to say–a middle-aged white man like all the other middle-aged white men. It’s a voice that constantly undercuts itself with self-deprecation about being derivative, boring, standard-American in order to head off the conclusion that the author really is derivative, boring, standard-American.

It’s the kind of thing that fits perfectly with the kind of white guy who goes to some lengths to pretend that he’s not a white guy.

Take the strange case of Tom MacMaster and Amina Arraf, where a straight man in Edinburgh pretended to be a gay girl in Damascus for the purpose of writing a blog called “A Gay Girl in Damascus,” becoming a minor Internet celebrity, having an online romantic relationship under the Arraf pseudonym, and eventually faking Arraf’s disappearance and possible death–Yi-Fen Chou on a much, much larger scale.

Why’d he do it? Because Amina mattered in a way Tom never could. Amina Arraf was unique as a well-known, heavily publicized young gay female Syrian putting herself out there on the Web, whereas White Dudes with Informed Opinions on the matter of LGBT rights in Syria are a dime a dozen.

Amina’s poetry about young lesbian love came off as raw, intimate, courageous; by contrast Tom’s poetry about young lesbian love came off as a sleazy fantasy. Amina’s accounts of life in Syria based on firsthand observation were fascinating and revelatory; Tom’s accounts of life in Syria based on research from books were competent but not brilliant.

Tom MacMaster’s viral hoax, interestingly, started with random posts arguing with strangers on the Internet and the skeleton of a novel–just innocently experimenting with trying on an identity more exciting than “boring white dude” and increasingly becoming addicted to it. His outing led to the outing of “Paula Brooks,” the lesbian founder of the Lez Get Real blog that hosted Arraf’s writings, as married straight man Bill Graber. Graber’s justification for his deception was similar to MacMaster’s–he was passionate on LGBT issues but felt his own stance as a sympathetic straight ally wasn’t interesting enough to hold people’s attention. He needed to fabricate a version of himself, a younger gay woman, who had life experience, who had credibility, who was less ordinary than him.

Look at the discussed-to-death case of Rachel Dolezal–keeping in mind that whatever reasons she gives for identifying as “transracial” today, she sued Howard University in 2001 because she thought her artwork was overlooked because she was white. Look at William Ellsworth Robinson, a.k.a. Chung Ling Soo, a stage magician so hungry for success that he ripped off not just the act and the shtick but the entire identity of rival Chinese magician Chung Ling Foo. Look at the stunt Kent Johnson pulled on the poetry world in the 1990s as “Araki Yasusada,” giving his poems the added historical weight of supposedly coming from the recovered notebook of a Hiroshima survivor. Take the mysterious, reclusive woman playwright who writes about women characters, Jane Martin, widely suspected to be well-known director Jon Jory using a pseudonym.

It’s an identifiable pattern. A white man in the arts trying to be someone other than a white man in the arts. A creative person, an artist, who wants their art to mean something because of their unique life experience–growing up in war-torn Syria, being taught magic by Chinese mystics, fleeing the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing–rather than being the result of the boring, workaday process of making shit up.

“Whiteness,” after all, in our racial system simply means ordinariness, unmarkedness, blankness. Same with maleness–being a guy means getting to be the default, being just a “writer” rather than a “female writer,” being just “in tech” rather than a “woman in tech”.

Ordinariness has tons of advantages. Being seen as ordinary means you don’t get stopped for shoplifting, it means you don’t get detained or shot or left to die in prison nearly as often. People don’t think twice before reading your résumé or renting your AirBNB. It’s much easier for you to wear what you want and buy what you want and live how you want without getting shit for it.

But ordinariness that’s maintained by constantly comparing yourself to other people who are not ordinary can be stifling. “Whiteness” can mean, in people’s minds, that you’re basic–that you’re a sheltered, boring person, that your point of view is the same as the default point of view everyone else has already heard, that you’ve got nothing interesting to say compared to what an exciting exotic foreigner might say. It’s a powerful force, the force that drives this thing we call “cultural appropriation,” this thing that makes people insist their little “affirmative action” scheme is what’s getting them published, this thing that makes other people concoct elaborate hoaxes almost guaranteed to blow up in their faces.

And it’s a mistake. Not just, as I’ve argued, because it’s bound to fail in the end. But because the premise it’s based on is false.

I do firmly believe, along with Sherman Alexie, that white voices have been privileged for way too long compared to nonwhite voices. But that doesn’t imply that white voices–or black voices, or Asian voices, or any other set of voices–are monolithic. It doesn’t imply that, say, there’s a certain Chinese-American “flavor” that all Chinese-American artists share and that the reason to add Chinese-American writers to your anthology is that it adds a certain spice to your stew.

That’s the logic of a lot of “pro-diversity” rhetoric, and I dislike it. People who think they’re helping the cause by talking about how intrinsically interesting and exciting and fun “diverse perspectives” are because of their diversity are just encouraging more white people to capture some of that sweet, sweet attention by becoming the next Amina Arraf or Yi-Fen Chou or Rachel Dolezal. That’s the kind of “pro-diversity” rhetoric that slides seamlessly into exotification, objectification, that uncomfortable feeling I know all too well of being trotted out into the spotlight as A Chinese Man and asked to talk about What Being Chinese Means, like an unusual laboratory specimen.

The fact is everyone feels ordinary, and boring, and insecure about whether their voice really matters. There’s no one so unique there isn’t a stereotype they’re worried they’re living up to. There’s no one so interesting they can’t think of someone else whose life experience is more interesting than theirs.

I’m a genuine 100 percent Ethnic Chinese-American dude–I’ve got the birth certificate to prove it–but I identified a lot with the speaker in “The Bees, etc.” I have that feeling of being all too painfully aware how my writing borrows tropes and clichés from other writers I’ve imprinted on, of how many things I think I “know” are just things I heard in the media and that I’m repeating. The simple fact that I’m Chinese doesn’t mean I know much at all about how the millions of other Chinese people in this country live–and it doesn’t make me immune to absorbing the same stereotypes that everyone else has. (I’ve had the humiliating experience of thinking I was coming up with an original quote about my childhood and then realizing I was just repeating “The Joy Luck Club.”)

Indeed, it’s the very fact that as a minority people expect you to be exotic, interesting and strange but you personally probably don’t feel very exotic most of the time that leads to what W.E.B. DuBois calls “double consciousness,” asking yourself the absurd question of whether you’re “black enough” or “Chinese enough.”

The hard truth is that while there are things people share based on categories like race, gender, class, etc., those categories are things that are done to us, not things that we are. Like other people I follow, I’ve come to prefer the term “justice” to “diversity,” because the reason to publish someone named “Yi-Fen Chou” over someone named Michael Derrick Hudson is not that anyone thinks Yi-Fen Chou has some essential magic ingredient of Chinese-ness that makes their work interesting–it’s that we have been blinded by a systematic irrational delusion in the past that people named Yi-Fen Chou were not worthy of publication, and we’re just trying to correct that bias.

For me, race is not about some essential magic ingredient of Chinese-ness. I don’t believe such a thing exists. And I want to reach out to insecure white people–no irony or condescension intended–and say you don’t have that much to be insecure about. People like me aren’t any more inherently interesting or worthy than people like you. I’m as much of a basic bro as you guys are.

I know I’ve been tempted to accept and play with the “positive” stereotypes associated with my own race–genius intellect, mysterious Eastern wisdom, all that noise–but that’s ultimately a bad deal. I don’t want to get sorted into a box that shunts me toward software engineering and away from writing poetry–all I want is to have my own chance to write ironic, self-deprecating poetry about bumblebees and Jesus if I really want to. A great deal of the freedom we’re looking for, as people who are stereotyped, is the freedom to be flawed as well as to excel, to be unique human beings who fall short of stereotypes as much as we excel beyond them. Justice, not the essentialist notion of diversity-for-diversity’s-sake.

Yi-Fen Chou and Amina Arraf and Rachel Dolezal are tragic. They’re tragic because they’re privileged people putting themselves in minority boxes, deluding themselves into believing the lie we’ve been fed all our lives, that boxes are an advantageous place to be. It’s a game that, even if it wins temporary rewards in the form of getting published in “Best American Poetry,” ultimately yanks us all back away from a world where we understand these categories as limited, false ways to understand ourselves and break out of them to be something more. It’s a game where we all lose.