During the Paris conference, climate change activists in New York marched behind a large banner reading “The Debate Is Over.” That may be true for scientists and for the diplomats meeting in Paris, but among politicians in the United States, the sad truth is that the debate has hardly begun.

Here is the scary truth that lies behind the Paris agreement headlines: Without significant changes in the GOP position on the environment, the Paris agreement, like each of the international climate agreements that preceded it, could very well fall apart, perhaps in as little as five years.

Under the Paris Agreement, the U.S. has three core commitments: to implement its initial target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, to pay billions to developing countries to induce them to make their own reductions, and finally, to commit to further reductions in 2020 and thereafter, as required under the “ratchet up” mechanism designed to keep global temperature increase under 2 degrees Celsius. If the train wreck that is American environmental politics prevents the U.S. from meeting these commitments, then the framework as adopted in Paris will likely fall apart.

So why, exactly, do we need the GOP in order to meet these U.S. commitments? At the broadest level, history teaches that it is unlikely that a project as complex, lengthy and consequential as the substantial decarbonization of the American economy can be achieved over the scorched-earth opposition of one of the two major political parties, especially if that party retains control of one or both houses of Congress.

The administration’s game plan is to meet the major part of our agreed reduction with the president’s Clean Power Plan, which was adopted by the EPA, but is under attack both from Congress (which has voted to overturn it) and in the courts. The president vetoed the congressional resolutions to rescind the Clean Power Plan, but if a Republican replaces him in the White House, he or she would almost certainly dismantle it. And even if the GOP does not retake the White House, the next president still will need to defend the tsunami of legal challenges launched against the Plan, and many commentators believe the whole thing will be finally decided in the U.S. Supreme Court.

If SCOTUS decides against the EPA, and the GOP still controls at least one house of Congress, then there is no clear path for the U.S. to meet its commitments, and the Paris framework will be at grave risk. Even if the Democrats hold the White House and the next administration defends the Plan and wins, Congress still holds the power of the purse and, if the House remains in GOP control, it is highly unlikely to appropriate the funds required to meet the financial commitments made by the president in Paris. The president’s 2016 appropriation request to meet U.S. obligations to the Green Climate Fund were denied, but last week’s omnibus funding deal appears to give the president enough flexibility to make some funding from discretionary accounts. House Republicans have already stated their determination to both block the appropriation and deny the president that same flexibility for fiscal 2017. Without the promised funding, it is highly unlikely that developing nations can or will meet their own commitments.

But even if we survive all of those hurdles, the U.S. needs additional national emissions reductions just to meet the initial target put on the table in Paris, and then in 2020 will be required to follow this with credible plans to implement further, deeper reductions. In the absence of another recession or unforeseen technological development, further economy-wide reductions would most likely require landmark legislation, such as cap-and trade, cap-and-dividend, or a carbon tax.

Put simply, America needs to perform if the Paris framework is to succeed, and for America to perform over the long haul, either the GOP needs to be denied the White House and both houses of Congress, or the Republican Party needs to change its position on climate change. Given that an era of continuous filibuster-proof Democratic control of all branches of government is unlikely to dawn within the next five years, the path to successful implementation would thus seems to depend on the GOP itself.

So, the real question we should be asking about the Paris agreement is whether there is any scenario under which the Republican position on climate might change, and how we can increase the likelihood that it does.

There is reason for optimism. The prospects for detaching conservatives from their knee-jerk opposition to the environmental agenda are better now than at any time in the past quarter-century. Millions of Republican voters—roughly 60 percent of them—say they are not members or supporters of the Tea Party. We don’t hear much from these moderate conservatives, because they are deeply overshadowed by what Jonathan Chait called “an imbalance of passion” when compared to “movement” conservatives. But there is every reason to think that this moderate vanguard, which will recover its voice when the influence of the Tea Party finally abates, will support a moderate Green agenda. This is illustrated by late 2013 polling by Pew, which shows that 61 percent (only slightly below the both-party national average of 67 percent) of non-Tea Party Republicans say there is solid evidence for global warming (compared to only 25 percent of Tea Partyers).

Let’s also remember that only eight year ago, climate change was one of the McCain campaign’s top priorities. Although the promising developments of 2007 were swamped by the politics of the moment, they give us a good idea of what could happen if the GOP finally emerges from the spell of the Tea Party.

On a different front, the emergence of a Green strain of Christian evangelicals raises the question of whether religiosity also might serve as a possible bridge between environmentalists and the right. “Creation care” evangelicals are being joined by a growing number of American Catholics, prompted by Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical letter, “Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home,” in which he forcefully asserts the moral case for environmental stewardship and climate action.

When the EPA held hearings on the Clean Power Plan, more than two dozen faith leaders, many of them from traditionally progressive congregations and traditions, but including some conservative and evangelical Christians, testified in support. The week before the pope’s address to a joint session of Congress, a brave group of 11 House Republicans, led by New York State Rep. Chris Gibson, introduced House Resolution 424, which calls on the House to address climate change, “including mitigation efforts and efforts to balance human activities that have been found to have an impact” on climate, stating that “it is a conservative principle to protect, conserve, and be good stewards of our environment.”

There is an emerging sense that many more GOP politicians are ready to reclaim a sensible position on climate change and environment, just as soon as the price—in terms of fundraising impact and the threat of being “primaried” from the right—is not too high. Eduardo Porter, writing in the New York Times, reported Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s belief that there are “eight, 10, maybe 12 Republicans in the Senate” waiting to break from the GOP’s anti-Green orthodoxy. “When the moment comes,” the Senator opined, “they could all jump together.”

Much depends on leadership emerging from the right. One inspiring example is six-term GOP congressman from South Carolina Bob Inglis, who traveled to the Great Barrier Reef and to Antarctica, spent time with climate scientists, and changed his mind about the reality of global warming—a change that cost him his seat in Congress, but launched him on a courageous campaign to convince conservatives to support revenue-neutral carbon pricing. An end to the right’s estrangement from the environment, like these other shifts, requires at least a few GOP leaders to conclude that the transition will advance the interests of conservatives or Republicans generally and to publicly embrace openness to at least part of the Green agenda. Even a subtle shift in “elite” opinion can create a safe place for individuals to reconnect with conservation without fear of apostasy.

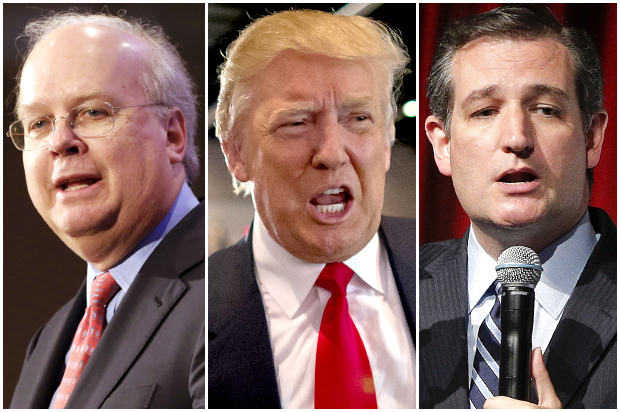

The greening of the GOP would be a good thing for the environment, but the bottom line, of course, is whether the GOP concludes that it also would be a good thing for the Republican Party. By 2015, only 27 percent of Americans polled thought the Republicans would do a better job than the Democrats in protecting the environment. Even Karl Rove, writing in Newsweek after the party’s losses in 2008, argued that Republicans need a “market-oriented ‘green’ agenda that’s true to our principles.” I have no doubt that leading figures in the GOP establishment pondering the electoral map for 2016 are keenly aware that swing states like Colorado, Iowa, Virginia and Wisconsin host large groups of Green voters. Eventually, they will understand that the usefulness of climate change ridicule to mobilize the ultraconservative base is outweighed by its tendency to repel swing voters.

This resurrection of the bipartisan consensus on environment that animated the Green movement at its inception is the subject of my forthcoming book, “Getting to Green.” The Paris agreement is an important achievement. But my analysis of environmental politics over the past 50 years suggests that actual meaningful progress in slowing the buildup of atmospheric carbon depends more on the harder project of freeing climate change from its place at the core of America’s hyper-partisan dysfunction.