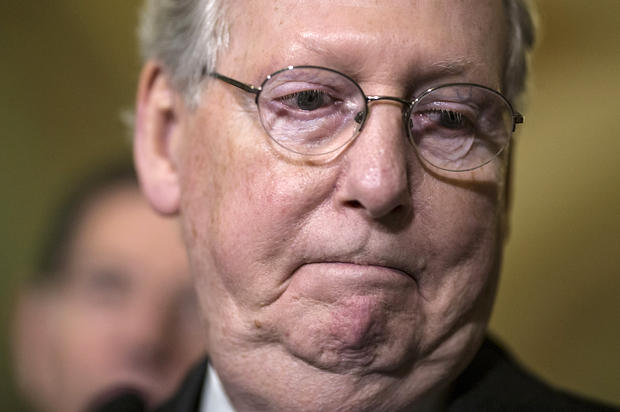

Mitch McConnell is in a wistful mood. After more than 30 years in the Senate, he’s finally living his dream as leader of the Republican majority. He has a new memoir out recounting his life spent in politics and government. And with his party on the cusp of nominating a toxic presidential nominee who threatens to damage down-ballot candidates and imperil the majority he won less than two years ago, McConnell is getting a little misty-eyed and sentimental about the institution that he, for the moment, controls.

Thus he’s written an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal laying out his vision of how the Senate is supposed to function in our system of government. “I love the Senate,” McConnell writes. “It’s the one institution that best combines Madison’s realistic recognition of human frailty with the lofty aspirations of a society that’s ordered toward liberty and opportunity for all.” But, he laments, the Senate has been hampered in its mission of late by the foul corruption of partisanship – a failing, he hastens to add, that is not his fault in any way. Responsibility for the breakdown lies, of course, with President Obama, who “is determined to force our country into the kind of progressive model that Western European societies embraced years ago, whether the rest of us like it or not.”

This isn’t anything we haven’t heard countless times from Republicans over the last seven years, but McConnell attempts to put things in a historical context – and in the process unintentionally stomps all over his own argument.

McConnell traces all the partisan acrimony to the party-line passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, and he sets that moment outside the historical trend of other issues of “great national significance.” He writes:

The lesson was clear: On issues of great national significance, one party should never simply force its will on everybody else. Medicare and Medicaid were both approved in 1965 with the support of about half the members of the minority party. The Voting Rights Act passed with the votes of 30 out of 32 members of the Republican minority. Only six senators voted against the Social Security Act of 1935. And only eight voted against the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. All of these were the mirror image of ObamaCare, which passed the Senate without a single vote from the minority Republicans.

McConnell doesn’t seem to have realized that he’s accidentally made the case that moments of “great national significance” tend to happen only when Republicans are in the minority and not unified enough to thwart them. But leaving that aside, he’s treating the fact of blanket Republican opposition to the ACA as a sort of historical oddity, one that he thinks proves that the Obama administration did something wrong. That’s one interpretation, but the more satisfying and more realistic way of looking at this is that McConnell himself has laid out the evidence for how the obstructionist strategy he proposed and implemented during the early years of Obama’s tenure was extreme and outside political norms.

To that point, McConnell’s explicit strategy was to enforce party unity in opposition to Obama precisely so he could wring electoral gains from the “failure” of the president’s agenda. He said as much to the New York Times in 2010:

“It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out,” Mr. McConnell said about the health legislation in an interview, suggesting that even minimal Republican support could sway the public. “It’s either bipartisan or it isn’t.”

Mr. McConnell said the unity was essential in dealing with Democrats on “things like the budget, national security and then ultimately, obviously, health care.”

Now, after engineering this historically divergent strategy of reflexive obstruction, McConnell is out there bemoaning the impact it’s had on his beloved Senate and making like he had nothing to do with it.