“Mom, have you heard about the Stanford swimmer?”

My breath catches as I look at my 9-year-old son sitting in front of me. The room fades away; I’m at a crossroads. Behind me is safe territory, of stuffed animals and lullabies and schoolyard games. Before me, an adolescent abyss, shrouded in fog and uncertainty.

I can step backwards, dodge the question, change the subject. Give myself more time, just a little more time; savor this sweet, all too transient age of innocence. Or I can summon my maternal courage, embrace the fear, and move forward, into the unknown.

I’m not ready for this. I don’t want to choose. I thought I had more time.

“Yes, I’ve heard about that,” I hear myself say. “What have you heard?”

I will myself to remain present in the moment and focus on the words coming out of my son’s mouth, rather than mentally prepare my next statement. He has heard about it on the evening news and on ESPN; he understands something has happened but he doesn’t know what.

“What did he do, Mom?”

Oh, my son. My first born, my heart. Look at your sweet face, how your freckles run across the bridge of your nose, hiding the faded scar you’ve had since you were 18 months old. I am remembering when, in the midst of a toddler tantrum, you slipped on our wood floor in socked feet, landing squarely on the edge of our coffee table. I picked you up, your blood spilling on the floor, on the table, on me. Your father and I rushed you to the emergency room in a panic, you clutching my chest as I pressed a blood-soaked towel against your beautiful face. A dozen stitches later, that night I learned I couldn’t protect you from the world forever. Today, I realize I still can’t.

“Well, he hurt a young woman, very badly. She’s alive, but what happened was very scary and still upsets her. And people are angry because even though he was found guilty, the judge gave him a very light punishment.”

“Why would the judge do that?”

I pause, and I feel the weight of this moment. Right now, RIGHT NOW, I am shaping my son’s views about race, gender, privilege, and morality. The gravity of this moment is not lost on me, though my words are.

“Well, honey, no one knows for sure why except the judge. But many people think – and I think so too – that a lot of it is because the Stanford swimmer is white and has money. And that if he weren’t – if he were black, or poor, or wasn’t going to a good college – well, he probably wouldn’t have gotten such an easy punishment.”

“Yeah,” my son says. “Like when that black kid was shot and killed for no reason. No reason at all. Just because he was black.”

My rapidly beating heart breaks. In this game of connect-the-dots, my son has decoded a picture of white privilege. He sees how his whiteness affords him not only privilege, but a reflexive safety and presumption of innocence that his peers of color don’t have.

“Yes,” I say. “I think you’re right.”

My son’s brow furrows. “How did he hurt her? Why did he do it?”

My dearest, my sunshine, how can I begin to explain this to you? Sex, consent, sexual violence – these are concepts far too advanced for the age of nine. I’m not willing to take you down this road. But I promised you that you could ask me anything and I would answer, and so I will do my best.

“You know, I don’t know why he hurt her. It makes me really sad to think that someone would hurt another person on purpose like that. So that’s why we always have to listen to other people and take care of them. If you’re playing with someone and they don’t want to play anymore, you have to stop. You can’t force them to keep playing. And if you see someone hurting someone else, or forcing them to do something they don’t want to do, what should you do?”

“I should help them. I should help stop it.”

“Right.”

“But Mom, what if… What if I hurt someone? I don’t want to, but what if I do?”

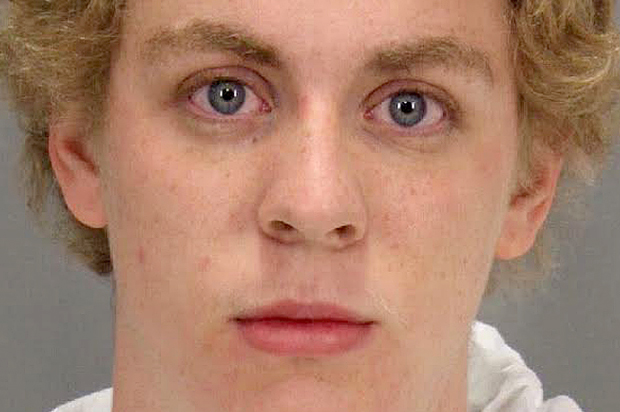

He has stopped me cold. Of all his questions, this one I didn’t anticipate. And in an instant, my thoughts turn to Brock Turner’s mother. I’ve read the indefensible statement Turner’s father made, my initial response one of disgust and rage. But when I think of her, another mother of sons, I cannot help but imagine what hell she is living, and how heavy a burden her guilt and remorse would feel.

“Well, sweetie, you have to do your best not to hurt someone. You have to treat everyone with respect and kindness. But if you do hurt someone, then you have to admit it. You acknowledge you did something wrong, you apologize, you ask forgiveness, and you do everything you can to make it better.”

He nods. “Yeah, you have to say sorry. And you have to really mean it.”

I tousle his hair. “Exactly. Any other questions?

He pauses, then looks at me. “Can we go to the pool?”

I nod, and he runs to find his younger brother. My hand finds the wall, steadying me as I take a deep breath, wondering if he will remember this conversation, knowing I will never forget.

This is our deepest responsibility. This is our charge. We can shape a new paradigm; we can abolish the culture of rape; we can combat the effects of racism. And it starts at (sadly) far too young an age, but such is the devastating truth of twenty-first century parenthood. Our imperfect words will catch in our throats and ring in our ears, and we will doubt ourselves and worry that we are ruining our children’s innocence.

But when they ask, we must answer.

This article first appeared on thescientificparent.org