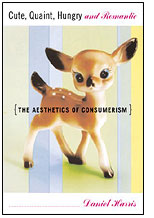

When writers pontificate about how some cultural artifact affects “us,” they generally mean their audience, or at least themselves. Daniel Harris takes a very different approach in “Cute, Quaint, Hungry and Romantic,” his jeremiad (his own word) against American consumer culture: He discusses the ways that product pluggers’ visions strike an “us” best characterized as nobody who could begin to understand the argument of his book — if in fact “we” exist at all. To Harris, “we” are a blank-minded mob of automatons who not only strive to keep up with the Joneses but require advertisers to tell us who the Joneses are.

Harris’ baleful premise is that popular notions of “cuteness,” “quaintness,” “zaniness,” “naturalness,” “cleanness” and so on are artificial fabrications of the capitalist machine. What we think of as our unique tastes are rooted in how we are sold what we buy; movies, TV and magazines shape our ideals. Take fashion photography, which, like most advertising, Harris finds “pornographic” in its soulless appeal:

Our lives are now mediated through the aesthetics of consumerism, through images so commanding that we imitate their inanimacy and deadness, which have become crucial components of the glamorous woman’s stylishness, her photographic remoteness and serenity.

Our yearning for cuteness, quaintness, etc., Harris says, tosses similar existential wrenches into our lives. Not only are such concepts fake, they and their fakeness have been absorbed as hulking pathologies into our collective psyche. For instance, according to Harris, “The basic credo of coolness is nihilism,” and so he deconstructs late singer Nico’s heroin addiction as a double-barreled pursuit of coolness and glamour:

Nico’s defacement of her own beauty to acquire the glamour of coolness shows how the aesthetic of ugliness, like the aesthetic of the teenager’s bedroom, is extremely moralistic, based on an almost evangelical contempt for the body, a Gnostic, self-hating puritanism.

Teddy bears are stump-limbed and obese; dolls’ eyes brim with tears; and we find Winnie-the-Pooh’s pratfalls and blunders adorable — thus, “cuteness is the aesthetic of deformity and dejection.” Commercial portrayals of happy couples “present a pastoral utopia in which all rivals have been ruthlessly liquidated through a type of aesthetic genocide.” When we eat natural foods, we’re not really concerned with our health but with “gnawing our way out of cities … getting so close to the earth that we actually incorporate parts of it into our body in a symbolic act of cannibalism.”

But there are some huge flaws in Harris’ misanthropic logic. Is addiction motivated only by a desire to look cool? Should children be denied teddy bears and given lifelike rat dolls with sharp claws and snapping jaws instead? Of course not. Stuffed animals have big eyes, ineffectual arms and round bellies because baby mammals (including baby humans) do, too, and the cuteness of babies appeals to our most primal emotions. But there’s no room in this essay for the emotions or, for that matter, for the down-to-earth reason of real people, millions of whom daily navigate the shoals of media drivel without Harris’ hothouse angst. He reduces virtually every impulse — hunger, humor, the way we choose to decorate our apartments or get dressed in the morning — to the brainwashing, often contradictory directives of marketing.

Harris is unfailingly clever; his observations are those of a gifted comic. But he leaves off the punch lines. He won’t acknowledge that he’s exaggerating, that nobody really believes most of what advertisers say and that when we do follow fashion, it doesn’t inevitably signal our corruption. His examples prove his point only if we accept his presupposition that we’re hopeless, hapless rubes.

While Harris identifies the culprit as capitalism, with its surfeit of unnecessary stuff and its requirement that we keep discarding the old and buying the new in order to keep the system running, he explicitly refuses to suggest any brighter path, any alternative to this abasement. But most of us simply don’t inhabit the shallow, desperate world of aesthetic torment that he portrays: We’re skeptical in the face of sales pitches and have the self-confident curiosity to select our own truths from the cornucopia of images that consumer culture foists on us. So, in the end, Harris’ eloquent tirade testifies less to the hideousness of consumerism than to his own consuming disgruntlement.