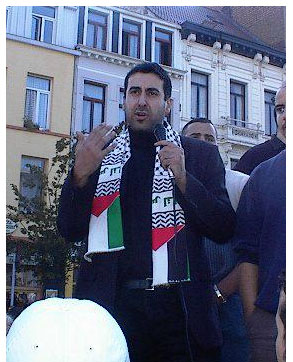

Shortly after 6:30 p.m. on a Tuesday in December, a young man named Ahmed Azzuz marched into a Belgian television station, burst onto the set of the evening news and, standing beside the startled anchorwoman and directly before the cameras, unfurled the red, black, green and white flag of Palestine. “Stop the hypocrisy!” he demanded in Dutch as news crews scrambled behind the scenes to regain control. It was the 16th anniversary of the first intifada, and Azzuz had a message: “Israel must vanish,” he said, his voice calm and even. “The killings of Palestinians must cease.”

When he had finished speaking, he calmly thanked the audience, rolled up his flag, and walked away. The whole episode took less than two minutes. Police were called, but lacking sufficient grounds for his arrest, he says, they simply gave him a ride home.

Azzuz is a founder and the Belgian president of the Arab European League, or AEL, an outspoken self-styled civil rights movement with a growing membership — and growing influence — in Belgium, the Netherlands, France and beyond. Combining Arab nationalism with impassioned Islamism, it positions itself as an uncompromising defender of European Muslims, eschewing assimilation and espousing confrontational political ideas such as the introduction of sharia law in Europe. It has warned of — or threatened — an “almost unpreventable” attack on Antwerp’s Jewish community if it does not “cancel its support for Jewish policy as fast as possible and distance itself from the state of Israel.” (Azzuz’s “Stop the hypocrisy” was a reference to those Belgian Jews who, he claims, join the Israeli army, which he sees as proof that Belgium is biased toward Israel.)

More recently, the Dutch faction of the League issued an invitation to Pakistani extremist Hussain Ahmed, leader of the Jamaat-e-Islami, a group with known ties to al-Qaida and the Taliban, to speak at a congress center in the Netherlands. (Dutch officials subsequently refused to grant Ahmed an entry visa, citing national security concerns; the AEL blamed “the Zionist lobby” for the decision.) The AEL has issued public approvals of 9/11, pledged solidarity with Iraqi insurgents and has challenged new French measures to ban Muslim headscarves in public schools.

Had Azzuz used his guerrilla TV tactic at an American network, it would have been national news — and he might still be in detention. In Europe, however, Azzuz’s piece of political theater aroused less outrage — in part because Europe, home to some 15 million Muslims, is struggling to figure out how to deal with the militancy of small but growing groups like the Arab European League without trampling on civil rights, and without alienating more moderate Muslims who are by far the bigger bloc.

To its defenders, the league is an uncompromising advocate for European Muslims, in the tradition of American blacks and Latinos who aggressively called for recognition in the ’60s. But to its critics, including some fellow Muslims, the league and its charismatic leader, Dyab Abou Jahjah, are a divisive and potentially destructive force, so provocative that some Belgian officials have sought to knock its Web site offline or even to have the group banned outright. In the wake of the March terror bombings in Spain and a pair of controversial new reports linking anti-Semitic acts in Europe to Muslim immigrants, Jahjah, Azzuz and their league allies are coming under closer law enforcement scrutiny and increasing political pressure.

Just before the Madrid attacks, the Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service disclosed in a report that the number of Muslim immigrants in that country being recruited by international jihadists had increased. Pinpointing groups like the AEL, the report warned that “a violent radical Islamic movement is gradually taking root in the Dutch society.” (The Dutch government has just learned that it could be targeted by al-Qaida, in part because of the radicalization of Muslims in the Netherlands, according to press reports. Spanish and Italian intelligence have reportedly heard on phone taps that a terrorist group is “standing by” in Holland.) And in a report by the European Union’s Monitoring Center on Racism and Xenophobia issued March 31, researchers found that young Muslims were the biggest force behind a wave of anti-Semitic incidents and attacks in Europe since 2001.

Far from apologizing, Jahjah and other league leaders have seemed to draw energy from conflict and controversy. The league has largely declined to condemn a wave of anti-Semitic acts by Muslim youth. League officials have offered no public criticism of the March 11 Madrid train bombings that left nearly 200 dead and hundreds more injured. (Authorities believe the attack was carried out by a Moroccan terrorist cell with ties to al-Qaida). Instead, Jahjah suggested in a televised debate that a similar attack was likely in the Netherlands. “It’s logical,” he said. “You make war with us, we make war with you.”

Despite their confrontational stance, AEL leaders insist that they advocate only peaceful methods of change: Jahjah has declared that “we are against violence.” But their stance is ambiguous. One line from the AEL manifesto asserts: “You don’t receive equal rights: you take them.” And the league’s Web site praises Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, the founder and spiritual leader of Hamas, who along with seven bystanders was assassinated in March by Israel in a missile attack. Yassin, the site said, is “an example for many of us.”

Somali-born Dutch Parliamentarian Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a former Muslim whose outspoken criticism of Islam’s treatment of women has made her the target of death threats from Muslims around the world, blasted this statement in a March 27 Op-Ed in the Dutch newspaper de Trouw. “A terrorist leader with the blood of hundreds on his hands is evidently a source of inspiration for the young men and women of the AEL,” she wrote.

Jahjah stirred more controversy in an open letter to U.S. President George W. Bush.

“Mr. President,” the letter reads, “we are a peaceful people, we do not attack unless we are attacked, we do not kill unless we are killed, and we do not aggress, we defend. If you want peace, you and your people, there is only one way, and that is the way out of our land.” But if the U.S. continues its close backing of Israel and “the Zionists,” Jahjah warns, and persists with its “aggression and occupation troops in Faloudja, in Baghdad, in Nadjaf, in Gaza and Jerusalem and Ramallah … more and more of your soldiers will undoubtedly rest in peace.”

It is the sort of rhetoric that has come to define the self-described “Arabian panther.” Eloquent, charismatic and Hollywood handsome — think George Clooney meets Robert de Niro — the 32-year-old Jahjah founded the Arab European League in Belgium in 2000, before the 9/11 attacks. Born in Lebanon and now a citizen of Belgium, he is part Malcolm X and part rock star. His makes no attempt to conceal his goal: He wants to introduce sharia — the religious laws and codes of Islam — to form what he calls a “sharocracy” in Europe. The sale of alcohol in grocery stores would be banned, as would sexually suggestive advertising. Islamic holidays would become national holidays, like Christmas.

Jahjah has spoken of the Sept. 11 attacks as “sweet revenge,” though the Dutch newsweekly HP/de Tijd quoted him as saying he would prefer to have seen empty planes crash the Pentagon and the White House. “I’d have found that quite beautiful,” he said.

Jahjah and his followers vehemently insist that Middle Eastern immigrants and their children must preserve their own culture and religion; comparing assimilation to “fascism” and “rape,” Jahjah demands that the cultural and religious traditions of Middle Eastern immigrants and their children be not just preserved but integrated into the culture of the West. “I’d rather die than assimilate,” Jahjah has said.

When asked by a Belgian television reporter if terrorism or a revolution were possible in the Lowlands, he offered a curt reply: “With the AEL, it could very well happen.”

Jahjah and the AEL burst into the headlines in November 2002, when Moroccan youths (Belgians of Moroccan descent are simply called “Moroccans”) looted shops, threw stones, smashed cars and staged a three-day standoff with police after a psychologically disturbed Belgian shot and killed a young Muslim teacher on the streets of Antwerp for no apparent reason. Belgian officials blamed Abou Jahjah. Though Jahjah insisted his only part in the event was trying to calm everybody down, police arrested him after the chaos had subsided and thoroughly searched his home. The AEL called this proof of Belgium’s ongoing vendetta against their movement; Belgian lawmakers contended that Jahjah posed a danger to the community of Antwerp. Jahjah was released after an Antwerp court ruled that there was insufficient evidence to hold him.

Either way, the arrest propelled his name and the league’s cause into the international arena. To some, he was a celebrity radical, an alluring combination of sex symbol and martyr; the Belgian media frequently called him the “black angel of integration.”

That was hardly the first brush with notoriety for the league. In April 2002, enraged by Israel’s massive military assault into the West Bank in response to a Palestinian terrorist attack, Moroccans and AEL members smashed the storefronts of Jewish-owned shops, calling for jihad and chanting “Osama bin Laden!” Before the U.S. invaded Iraq a little over a year ago, league members hurled rocks and Molotov cocktails during anti-American demonstrations staged at the Antwerp harbor.

In 2003, almost a year after Pim Fortuyn’s assassination, the league opened a Dutch chapter; soon after, Mohammed Cheppih was appointed to head it. But earlier statements from Cheppih supporting suicide bombers in Palestine and the death penalty for homosexuals provoked such an outcry that he was forced to step down. Still, he remains an influential consultant to the league.

Today, behind a motto that is early Malcolm X — “by any means necessary” — the Arab European League reports steady growth, with members now in 12 countries. In Holland, it says, membership has surged from 200 in March 2003 to about 1,000 now. A new office has opened in France, and last summer, the league deployed a new political wing, the Muslim Democratic Party, to represent its views in European Parliamentary elections this year.

For its adherents, the AEL offers a united platform and an amplified voice. This is especially true for the second- and third-generation children of immigrants who came here — primarily from Turkey and Morocco — as guest workers in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, kids struggling to define their identity in a post-9/11 and increasingly nationalistic Europe. The children and even the grandchildren of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants are still considered “Turkish” or “Moroccan,” rather than Dutch or Belgian. To these boys, Jahjah is a role model, a hero; for girls, he is a star. One newspaper quoted a young girl saying to Jahjah’s bodyguards outside a talk he gave in Holland: “I just want to see him in the real.”

In person and via the league’s Web site, Jahjah speaks directly to these disenfranchised youth. He is deeply mistrustful of the Western press, arguing that no matter what he says, he will be misquoted or that his words will be twisted by “the Zionist lobby” in an effort to turn popular opinion against him. Non-Muslim reporters are barred from Jahjah’s lectures and speeches, and he pointedly ignored Salon’s several attempts to reach him. Other AEL officers rarely speak to non-Muslim members of the press.

However, Jahjah’s Belgian lieutenant, Azzuz, agreed to an interview in December, after a series of protests that led to the arrest of 10 league members — including some who hung the Palestinian flag over the Dutch Parliament building in The Hague and Azzuz’s own television caper. Speaking by phone from Antwerp, the 27-year-old Belgian AEL leader, the son of Moroccan immigrants, was cordial but direct. The deaths of 9/11 were “collateral damage” — a term, he says, that Muslims learned from Americans. “Finally, something had happened to those who kill our women and children,” he said of the terror strikes that have reshaped world politics. “But America still blames others. They didn’t learn their lesson at all.” What lesson is that? “Stop supporting the terrorist state of Israel,” Azzuz replied. George Bush “doesn’t hold the strings,” he says, the Zionists do.

Relations between the peoples of the West and the Middle East have deteriorated to such a point, Azzuz said, that “something like Sept. 11 is likely to happen again.”

Belgium is a world capital of the diamond industry; it is a small but powerful engine of European capitalism, a bastion of conservatism and home to a large population of Orthodox Jews. It has long struggled to reconcile the submerged cultural conflicts between its Flemish, or Dutch-speaking, culture and the French-speaking Walloons. Neighboring Holland, by contrast, is a tiny country with a large reputation for liberalism and tolerance. In “coffeeshops” throughout the country, menu items for “Colombian” and “Purple Mountain” refer not to java but to varieties of marijuana; in the winding streets of Amsterdam’s red light district, women pose in lingerie before the windows. It is here that same-sex marriage and doctor-assisted euthanasia were first made legal.

But the two countries share a common dynamic: As their Muslim populations have grown larger and more restive, both have spawned a sometimes fierce anti-immigrant backlash. The result has been a cycle of building hostilities between Muslim and European in which it is usually impossible to tell who threw the first stone.

The influx of Muslims into Holland, Belgium and the other nations of Europe is hardly new. Tens of thousands have arrived, mostly from Turkey and Morocco, since the 1960s and 1970s. Those in the first wave, like immigrants everywhere, often came looking for political freedom and economic opportunity. Even now, though, the grandchildren of those immigrants say they often feel like second-class citizens in the countries they call home. The immigrants’ levels of education are generally lower; for them and their children, unemployment rates are higher. In Belgium, unemployment among Muslims is estimated at up to 40 percent.

Still, the population of Muslims in Europe continues to grow. According to one recent report, it could nearly double by 2015, approaching 30 million.

Almost a million Muslims now live in the Netherlands, giving the country the second-highest Muslim population per capita in Europe, after France. In a country still coming to grips with its guilt over the large numbers of Jews deported during the Nazi occupation more than 60 years ago, many are reluctant to discriminate against a different religious group, even if that group stands opposed to Holland’s famed liberal and secular mores.

But after some Dutch Moroccans openly celebrated the 9/11 attacks, and after a radical imam in Rotterdam pronounced that “homosexuals are pigs,” many among the Dutch were pushed over the brink. The rightist sociology professor Pim Fortuyn rose suddenly to political prominence, inaugurating his own party which he led into Parliamentary elections. Fortuyn, a gay man, ripped Islam as a “backward culture” and called for tough new curbs on immigration. Though he was assassinated in the spring of 2002, his party swept to power with considerable support from voters under 30. Though Fortuyn’s party did not hold power long, its powerful influence is still felt in strict new immigration rules and the planned deportation of 26,000 failed asylum-seekers.

The rise of far-right parties like Lijst Pim Fortuyn and Belgium’s Vlaams Blok and the popularity of right-wing leaders like France’s Jean-Marie le Pen has made European Muslims feel increasingly unwelcome, even hated. “People are getting angry,” says Ayhan Tonca, chairman of Holland’s largest organization of Turkish mosques.

The international political climate in recent years has further eroded tolerance and goodwill on both sides. The bloody Israeli-Palestinian conflict has inflamed Muslim animosity toward the West, a rage fueled by Arab news stations and Internet sites that beam graphic news and propaganda into Muslim homes throughout the West, thousands of miles from the zones of conflict.

In that atmosphere, the rhymes Moroccan youth chant beneath the stormy skies and along the cobbled streets of Holland’s Jewish neighborhoods have become frighteningly familiar: “Hamas, Hamas, alle Joden aan het gas!” they cry. (“Hamas, Hamas, all Jews to the gas!) Or: “Joden moet je doden!” which translates with chilling simplicity: “Kill Jews!” On May 4, 2003, during a national moment of silence in remembrance of those who perished in Holocaust, a group of Moroccan boys began playing soccer with the wreath Holland’s Queen Beatrix had placed by the Holocaust Memorial at the Palace in Amsterdam. There is an increasing incidence of race-based crimes, such as the recent murder of a teacher by a Turkish student in The Hague. “The teacher dishonored him,” one friend of the confessed killer, known only as “Murat D.,” explained to the media as other Turkish classmates chanted, “Murat, we love you!”

And while Jewish schoolboys in France now leave yarmulkes at home because the law demands it, in Holland, they do so out of fear. Indeed, the Dutch Center for Information and Documentation on Israel reports a 140 percent increase in anti-Semitic acts in the year 2002 and first half of 2003. That number “omits any act that could be viewed as anti-Israel,” says the center’s director, Ronny Naftaniel.

“There were some 330 incidents last year,” says Naftaniel, who estimates that 75 percent were perpetrated by Moroccan youth. “There is a minimal amount of anti-Semitism that is constant in Holland, of course, but if you blame Jews for being the world power who direct the politics of the world, if you throw stones at Orthodox Jews, if you chant ‘Hamas, Hamas’ on trams and buses in the cities, that’s anti-Semitism, and that’s a problem.”

Some Muslim leaders also acknowledge rampant, and often rabid, anti-Semitism in the Muslim communities here; even Jahjah and other AEL officials have, on occasion, spoken against it. But not Naima Elmaslouhi, the Arab European League’s vice president in Holland. Speaking briefly by cellphone from the Amsterdam police station in December, as she waited for the release of fellow league officers arrested during a pro-Palestinian demonstration, she said the claims of anti-Semitism are exaggerated. “It’s just one or two incidents,” she said.

Perhaps the clearest expression of who Jahjah is and what he wants comes in his book, “Tussen 2 Werelden: Roots van Een Vrijheidstrijd,” or “Between Two Worlds: The Roots of a Freedom Fight.” Published late last year by the prestigious Dutch-Belgian publisher J.M. Meulenhoff, a house known for its strong list of Jewish literature, Jahjah’s memoir-cum-manifesto suggests that ambiguity and contradiction are central to his character — and maybe to his strategy.

Born and raised in Hanin, in south Lebanon, Jahjah grew up in the midst of that country’s civil war and Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, which culminated in the 1982 slaughter in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatilla, where an Israeli commission of inquiry found that Israeli forces and their commander Ariel Sharon were indirectly responsible for the massacre of at least 800, and perhaps as many as 2,000, Palestinian civilians at the hands of Israel’s Christian Phalange allies.

In the early 1990s, at the age of 19, Jahjah traveled to the West; he applied for political asylum in Belgium, telling immigration officials that he’d been a member of the militant Shiite group Hezbollah and was seeking to escape its persecution. When authorities began to question his story, he married a Belgian ex-girlfriend, receiving residency as her spouse. The couple divorced shortly after his papers came through. Since then, he has denied he was a member of Hezbollah, saying he made the story up to get asylum.

The league, Jahjah says in his book, isn’t especially radical, but rather a “healthy, democratic protest organization born of the frustration and disappointment and hurt” of its members, a movement that seeks only equality and freedom. Only action, maintains Jahjah, will produce change. Azzuz agrees, saying that sometimes a bit of civil disobedience is necessary to win attention. “It’s not like we take hostages,” he says. But in another passage, Jahjah’s book also contains a somewhat different message: “Violence is no solution,” he writes, “but it can open the way to a solution.”

In his book, Jahjah claims people wrongly accuse him of ties to al-Qaida when in fact, he says, it is the AEL that is terrorized. Bodyguards protect him from the many domestic and international organizations that he claims want him dead, including Israel’s Mossad. (Israel dismissed the charge as “laughable.”)

But critics see evidence of the league’s character not only in what Jahjah says and does, but equally in what he doesn’t say:. For instance, neither he nor the AEL condemns al-Qaida. And while it would be unreasonable to blame Jahjah, Azzuz or the Arab European League for the wave of anti-Semitism, they are widely seen as contributing to the climate of rage and polarization, if only by issuing mixed messages.

This impression was strengthened last November, after terrorists suspected of al-Qaida links killed more than 50 people and injured hundreds in four bombings in Turkey — including two bombings at Istanbul synagogues. Some in the AEL did publicly condemn the attacks. But Elmaslouhi, the Dutch league’s vice president, voiced “support and understanding” for the bombers. “I am against the killing of innocents,” she told the Dutch newspaper Algemeene Dagblad, “but how do you know who is innocent?”

To some critics, Jahjah, Azzuz and others in the Arab European League seem less interested in multicultural harmony than in hostile separatism. These critics warn that a militant “Arab pride” movement poses risks that far surpass mere social tension.

The recent report by the Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service noted that self-styled mujahedin “purposefully influence members of the Muslim communities in the Netherlands in order to create a polarization in society and to alienate the Muslims from the rest of the population.” The effect, according to the report, is to strengthen their recruitment efforts by “appealing to the idea that the rights and interests of ‘good’ Muslims are being violated time and again.” As proof of the potential danger, the report cites the example of two Dutch-Moroccans who were killed in Kashmir while training for jihad.

Such concerns have provoked officials in both Belgium and Holland to wonder whether the Arab European League should be banned. In Belgium, Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt has called Jahjah a “threat to society,” though his effort to shut down the AEL on the grounds of “inciting violence, issuing threats and disturbing the public order” — a move Jahjah ascribed to “the Zionist lobby” — failed.

But when the AEL posted its statement supporting Hamas founder Yassin on its Dutch-language Web site, motions were filed in the Belgian courts to have the page, if not the entire site, pulled from the Web. While the courts debate, the provider serving the site has cancelled the League’s account, forcing it to scramble for another and rebuild essentially from scratch. (The English version of the site remains for the most part intact.)

But some are concerned that banning the league would only send the movement underground, making it even more dangerous. “At least, it’s out there in the open,” says Ayhan Tonca, who heads the organization of Turkish mosques in Holland.

For their part, AEL members accuse European officials of criminalizing their movement and exaggerating the social problems within the Euro-Muslim community. Even if that’s true, the increased pressure on the league and allied groups is likely to increase the tension. As with the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians and the widening conflict between Islamist groups and the West, it sometimes seems that there is no middle ground.

Tonca, speaking from Holland’s Turkish community, says he understands the appeal of the Arab European League, and cautions that Europe has no choice but to accept a cultural evolution. “We have to accept that Muslims are a part of Europe,” he says. “It isn’t just a Judeo-Christian culture anymore.”

Moroccan-born Mohamed Sini, a Dutch Labor Party official who chairs the organization Islam and Citizenship, calls the league an “extremist group” that only exacerbates tensions. Tonca, too, accuses Jahjah of being not much different than his opponents — Fortuyn, le Pen, the Vlaams Blok. All, he says, divide in anger rather than unite in peace.

The European establishment is wrestling with similar worries. Last December, the European Union shelved a report that blamed Muslims for the recent wave of anti-Semitism; when a new draft was issued last month, it blamed neo-Nazi and other racist groups, with Muslims being only a secondary cause — even though the numbers in the report showed that Muslims were in fact behind most of the incidents.

But to those who say that Europe must become a melting pot now in a way that it has not been in modern times, Jahjah and other league members say they’re not interested in blending in.

Absorbing the principles and norms of Holland, Belgium and other European democracies, they say, would mean sacrificing their integrity, their identity as Muslims. Rather, they argue, the Judeo-Christian majority of Europe should incorporate Islamic norms and values into its own. “Europe would be a better, safer place,” a message on the now-defunct Dutch Arab European League Web site proclaimed, “if it observed the values and the norms of Islam.”

“As a minority group,” says Azzuz, “we have rights.”

“Idiocy!” Naftaniel snaps in reply. “Integration doesn’t ask that you give up your culture.”

Despite the league’s plans to expand its presence in the coming year, especially in France, Naftaniel, Tonca and Sini all maintain that the movement will eventually fall by the wayside. “They fail to serve the real concerns and interests of [European] Muslims,” Sini says, “mostly because they blame everyone else for the tensions without looking within themselves.”

But he is nonetheless concerned, both about the AEL’s actions and about the responses they engender. “Extremism,” he warns, “breeds extremism.”

Tonca likewise worries that Abou Jahjah’s call will produce Turkish militants. “The most dangerous terrorists are those who are well educated in the West,” he notes, “and I fear that the Muslims who are educated here are becoming radical.”

Separation, Naftaniel says, is not compatible with democracy; coexistence requires collaboration and cooperation. “If one believes in democracy,” he says, “then the most challenging thing is to sit down with those who with whom you differ.”

That might be the starting point for détente, but does the league want détente? Its signals have been mixed, at best. Jahjah himself has publicly denounced the chants of “Hamas, Hamas, alle Joden aan het gas!” Elsewhere, though, he has expressed impatience with talk of peaceful coexistence. “The days of sharing couscous with a Jew are over,” he told Belgian newspaper De Morgen in April 2002.

Another top league official, apparently distressed by reports that Muslim children in Holland refuse to listen to classes about the Holocaust, wrote in a statement on a league site that the organization is “against each and every form of discrimination and racism. As Muslims we see the Jews as ‘the people of the book’ and it is obligatory to fight the hate against these people.” But the statement continues: “With equal fury the AEL fights Nazism and Zionism.” This association of Israel with Nazism, common these days among European Muslims, is widely seen as a crude and inflammatory form of anti-Semitism.

Which to believe, then — the overtures of peace, or the rhetoric of fury? In the interest of the vrijheidstrijd, or the freedom fight, Jahjah wraps himself in the mantel of the American revolutionary hero Patrick Henry. “We seek only to live in peace and with the freedom to live our own lives with equality, appreciation, and respect,” he writes in “Between Two Worlds.” “And if anyone tries to remove that right and to oppose us, we will fight until the oppression stops, and we acquire freedom — or die in the attempt.”