“Between Page and Screen,” a groundbreaking collaboration between poet and book artist Amaranth Borsuk and programmer Brad Bouse, is truly a first: a book that only can be read when simultaneously using a codex book and a computer’s webcam. When placed in front of a webcam, the black shapes printed on the pages, sans words, trigger animated text on the screen, revealing a correspondence between characters P and S.

“Between Page and Screen,” a groundbreaking collaboration between poet and book artist Amaranth Borsuk and programmer Brad Bouse, is truly a first: a book that only can be read when simultaneously using a codex book and a computer’s webcam. When placed in front of a webcam, the black shapes printed on the pages, sans words, trigger animated text on the screen, revealing a correspondence between characters P and S.

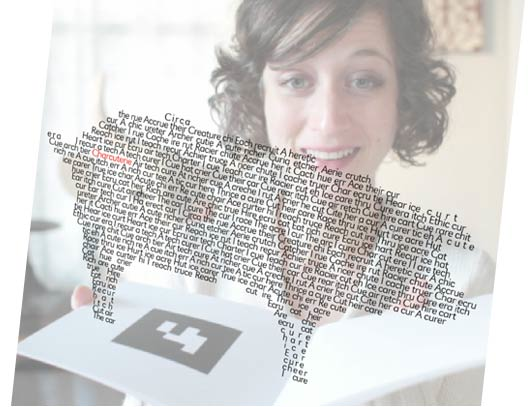

via Between Page and Screen

As e-readers continue to gain market share within the publishing industry and the “future of the book” remains a much bandied about phrase among publishers, writers, agents, booksellers and readers, “Between Page and Screen” has embraced the what-ifs and used them to achieve their true potential, an astoundingly realized book that shuns either/or designations. It champions both the book’s esteemed history by valuing ink printed on the page and also celebrates the potential of digital technologies that are resulting in all of us, no matter our preferences, having to change how we read.

via Between Page and Screen

“Between Page and Screen” is an entirely new reading experience, and no matter if you favor codex books or e-readers, reading this book makes you acutely aware of the act of reading it. Properly situating the book in front of your computer’s webcam takes a bit of practice but once you get the hang of it the pun-rich missives between P and S are unleashed. Certain entries initially show up on the screen as if you are reading them in a mirror, and it takes some maneuvering to arrive at that aha moment when you realize you just need to turn the page around to invert the text. Soon enough, the reading experience pulls you in like any other. Word-play animations splice up the word “hear” into “he” and “ear.” The letters between P and S speak to the project’s larger themes, making assertions like “page don’t cage me in” and “a screen is a shield, but also a veil,” asking questions like “What are boundaries anyway?”

Clearly, for the authors, boundaries are little more than challenges, which they have met head on, daunted not in the least, creating a reading experience unlike any other. Innovators like Borsuk and Bouse prove that the future of the book should be something we all consider with optimism provided we think beyond current expectations and strive to build new ones.

The authors were kind enough to answer the following questions via email.

via Siglio Press

How did the project take shape? Did the two of you set out to make the book as it exists or did it grow out of various other projects and interests?

We did set out to make the book as it exists. The content and the construction arose together out of our conversations about augmented reality (AR) and the way it puts text between the page and screen. In thinking about the relationship this sets up between print and digital objects, we got the idea for an artist’s book that explores that between space. We had been talking about collaborating on a project for some time, but we didn’t want the digital aspect, which is Brad’s specialty, to seem simply “added on” to the poems, which are Amaranth’s specialty. We wanted there to be a reason to use new media, and AR provided us the perfect marriage of print and digital that wouldn’t privilege one over the other, and that would highlight the importance of the reader in activating any book’s text.

What do you mean in saying that augmented reality “puts text between the page and screen”?

We mean that the text is not available on one or the other platform, but in the between space opened up by the reader who has access to both. On its own, the book provides only minimalist grid shapes and the screen provides only the reader/viewer’s image. But when the two are paired, the text appears – and it’s at that very juncture where the reader’s image and the book object meet that the words arise.

Had you already written the exchanges between P and S?

Once we had the idea for an exploration of the relationship between page and screen, the “relationship” began to take shape in relation to a number of literary forebears that use the conceit of letters, from Ovid to “Griffin and Sabine.” Amaranth then started to write the letters P and S trade back and forth.

Is this project a natural evolution in your background as a poet and book artist, Amaranth, or is it a result of feeling unfulfilled by traditional codex books as they exist in today’s screen-based culture?

I see it as a natural evolution. I’m not dissatisfied with codex books at all – I think there are certain things they do incredibly well, and other things that e-books and electronic literature works do well. I am, however, interested in our changing relationship with book objects and the way the shape of the book is changing in response to the proliferation of screen-based reading devices. For me, the most important thing is that the book has some reason for the form it takes. “Between Page and Screen” simply wouldn’t be the same book if the poems were printed on the page or at a website. It needs the “between” in order to make sense. I don’t think all books need to go that route, and I’m ready to turn to whichever apparatus best helps me tell the story I want to tell or explore the themes I want to explore.

via Between Page and Screen

More and more I’m convinced that the essence of a story is indifferent to technological developments. What changes is how the story is told or delivered, enhanced or altered by cultural shifts, from how the oral tradition faded away with scrolls and the printing press, etc. What would you say to that?

If you mean that the hallmarks of engaging writing remain largely unchanged despite technological shifts, I would say there’s some truth in that. But I do believe that the experience of reading a story changes with the medium through which we receive it. “Between Page and Screen” wouldn’t be or do exactly the same thing if the poems were printed in a book. Primacy would be given to the page.

I do think that where poetry is concerned technological shifts can have a dramatic effect on the shape and content of the work (the impact of the typewriter on the “look” of 20th-century poetry is well-established, for example). And ideological shifts in what writers want to do with poetry influence its shape as well. I don’t know that there’s a single “essence” of poetry that remains unchanged over time, unless we talk about it as an engagement with language. But there are so many different kinds of poetry that it becomes difficult to generalize, I think.

In setting out to create “Between Page and Screen” were you aware of early experiments in electronic/digital books and their presentation, like Robert Coover’s Cave and Bob Stein’s Institute for the Future of the Book?

Very much so! Amaranth is a member of the Electronic Literature Organization, and has been studying new media writing since she was in graduate school at USC (coincidentally, that’s where she learned of Stein’s work with if:Book). Her dissertation on poets’ use of writing technologies that allow for a distributed idea of authorship spanned from modernism to contemporary digital poetry, and she has studied and written on interactive text works from early hypertexts, to Flash animations, to crowd-sourced poems.

Amaranth, in your dissertation what sorts of “writing technologies” are you referring to in terms of modernist poets? I’m imagining Pound in his cage in Italy, watching birds and scrawling Chinese characters in the dirt with eucalyptus nibs. Is that what you mean, or is it more about carbon copies and linotype?

My dissertation primarily concerned Swiss poet Blaise Cendrars’s use of the typewriter (he had lost a hand in the First World War and it facilitated his writing greatly, but also served as a kind of muse and musical instrument) and American poet H.D.’s use of projective mediumship (the figure of the medium who can project images out of her body and into the room around her recurs in her WWII writings). I connect these poets to contemporary writers for whom technology offers access to a world of language outside the poet and a kind of collaborator in putting words on the page (both writers suggest that the words are being channeled through them thanks to the machine). Pound was highly skeptical of what H.D. was doing in the war years, especially her spiritualism.

via Siglio Press

What books, films and/or artworks do you count among your favorite in terms of helping to inspire “Between Page and Screen?”

Dieter Roth’s artist’s books, particularly his die-cut books, were definitely an influence on the shape of the book and the cover. The poems were heavily influenced by concrete poetry, particularly the work of Emmett Williams (whose “Sweethearts” is one of Amaranth’s favorite books), Mary Ellen Solt and Decio Pignatari, among others. In the electronic literature world, Camille Utterback’s “Text Rain” is also an inspiration. The epistles themselves are influenced by and draw heavily upon the “American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Word Roots.” I’m sure there are more that we’re forgetting!

Would you expand a bit on how the Indo-European word roots play into the letters?

The letters are full of puns, homophones and word play using words that share the Indo-European roots of “page” and “screen.”

Page comes from the roots pag- and pak-, which means to fasten or join together. It gives us words about connection, like “pact,” “peace,” “appease,” “pacify,” “pawl,” “pole” and “peasant.” The Latin root of page, pagina, means trellis (so at its heart, the page is metaphorically a trellis to which lines of writing are affixed).

Screen’s root (s)ker-, means to shine, and it develops from a form that means to cut (the metonymic connection is that many cutting implements have a sheen). That root gives us words about protection and defense like “scabbard,” “shield,” “skirmish,” “shear,” “score,” “carnage,” “carrion” and even “charcuterie” (from the Latin root caro, for flesh).

While the two different roots, one peaceful, the other militaristic conjure up two different personalities, there are points of connection between them “Screen” gives us a few connecting words, too: “share” and the other “sheer,” as in translucent, also “incarnate.” Peace loving “page” gives us the violent “fang,” “impale” and “impact.”

The poems play with those etymologies, giving the two bits of banter about their romantic compatibility.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2012.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America’s oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.