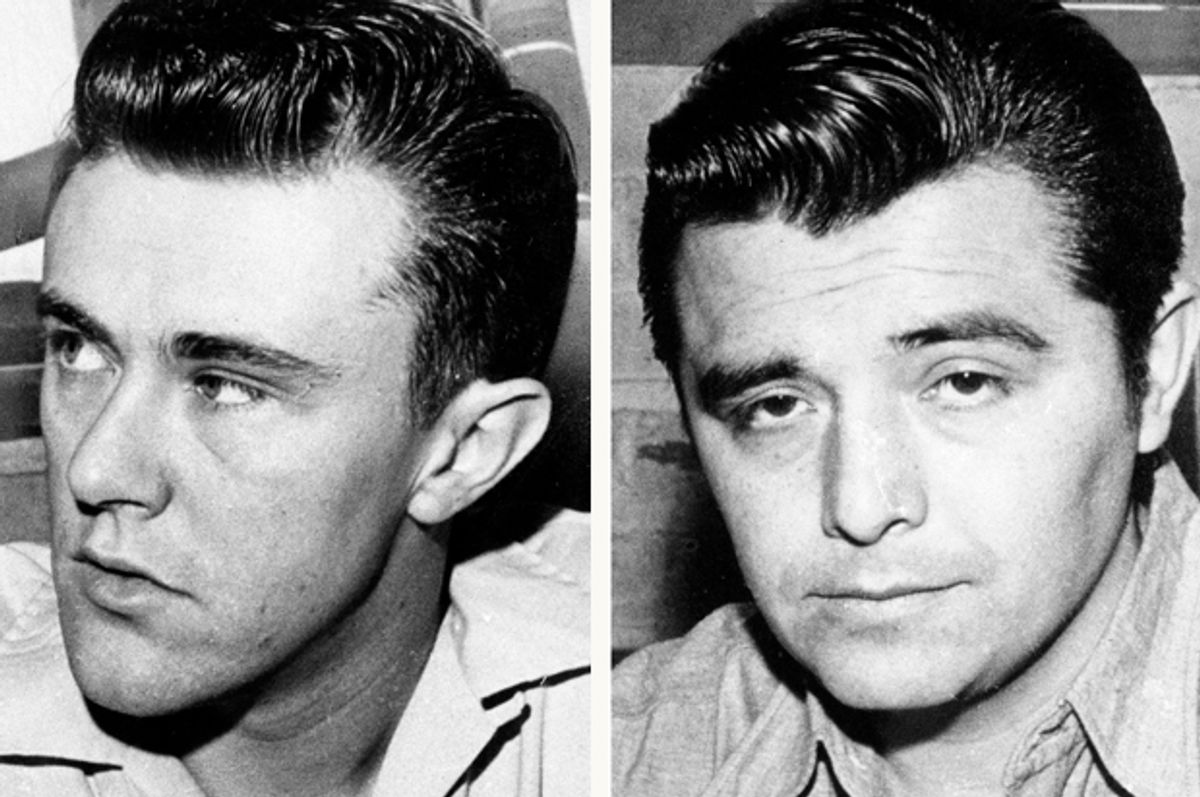

Fifty years ago tomorrow, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith, the two murderers made famous by Truman Capote’s "In Cold Blood," were hanged at the Kansas State Penitentiary.

Hickock and Smith had been convicted five years earlier for the brutal murders of Holcomb, Kansas, farmer Herb Clutter, his wife and their two children: Hickock had heard from a former Clutter employee that this farmer, and former member of the Federal Farm Credit Board, kept a safe in his house with $10,000 in it. No such safe existed. For their efforts -- a nighttime robbery and multiple homicides -- Hickock and Smith earned $43, a radio and a pair of binoculars. After an extensive manhunt, they were apprehended in Las Vegas.

For the witnesses present, this was no routine execution. Indeed, for one of them, Truman Capote, it was the obvious conclusion to his book examining violence in America through the lens of the Clutter case.

Hickock and Smith were executed just after midnight on April 14, 1965, in a dumpy warehouse with stone walls and a large gallows on which hung two nooses in a corner. They were dispatched in alphabetical order as a driving rain hammered the warehouse roof. Hickock was the first to go and was pronounced dead at 12:41 a.m. Smith was dropped at 1:02 a.m. and was pronounced dead at 1:19 a.m.

In June of the same year, George York and James Latham were also hanged for multiple murders. Kansas hasn’t executed anyone since 1965. For years, the state gallows (built in 1944) collected dust in that warehouse, still intact but simply taking up space. In 1986, officials from the State Penitentiary in Lansing contacted the Kansas Museum of History to see if they wanted it. Museum officials found the gallows completely intact. They took it apart, transported it back to the state museum and put it in storage, where it's been ever since. The governor at the time opposed capital punishment, and as such opposed exhibiting it; and besides, there was no room for it in the museum.

It has never been displayed, as one former museum curator told me, partly because anything associated with the death penalty is complicated to put on exhibit. Shown from one angle, it might look macabre; from another it might not look macabre enough. They’ve talked about setting up in the lobby of the museum, according to curator Blair Tarr, but the space is often rented out for parties and the like.

“It might put a damper on festivities,” he chuckles.

But really, Tarr says, it’s the Clutter murders. That’s what prevents them from displaying the gallows. “Even after, what is it now, 56 years? It’s still extremely sensitive, particularly out around Holcomb and Garden City. Members of the Clutter family are still around.”

Hickock and Smith weren’t the only people hanged on that gallows. There were 19 altogether—15 by the state and four by the U.S. military. But it’s those two who are remembered the most.

Tarr escorted me through the warehouse and up to the third floor, our feet clang-clanging across the metal floor. He points to objects along the way—a pinball machine here, some bullets there; a Carrie Nation poster here, the original gravestones of Hickock and Smith there. (They were stolen and ended up on a farm in southeastern Kansas.) We walk down the narrow aisles between shelves on the third floor and over to a corner.

“There it is,” he points.

Several piles of wood. Some stairs. Boxes with screws and nuts and bolts. There are notes attached to various pieces explaining what the pieces are and where they should go, but the curator tells me that, if it ever gets put back together, there’s going to be a whole lot of trial and error in the process.

Tarr says that a few others have come to see the gallows before me, but not many—mostly television stations wanting a shot of the trapdoor and stairs whenever they’re doing a story about capital punishment. There are some folks in Lansing who’d like to put it in a museum there. But people from the Holcomb area say it sounds like they want to use the gallows for tourism.

We walk back down the stairs to look at the platform, which rests on its side in a rack full of other items. As I walk around to the other side to get a better look at it,, Tarr says, “And you’re about to pass by the trapdoor.”

I pivot and see it, a long black metal lever attached to the metal trapdoor. It’s stunning, in a way. The handle is grey, seemingly worn away from use or just a bad paint job—it’s up on a platform to protect it from flooding.

I’m mesmerized by the worn handle of the trapdoor. I look at it closely and get the courage to touch it. I think of all the people who have touched this thing. It’s a strange sensation, at once sinister and sad.

“Through that,” Tarr says without prompting, “19 people met their end.”

Deconstructed, disassembled, scattered in parts about the warehouse, the gallows still carries meaning. And to reconstruct this machine would require much effort; building it in the first place certainly did.

It’s no surprise that the curators of that gallows don’t know what to do with it. It’s a horrible reminder of a multiple murder in Kansas and its consequences, but it’s also a reminder of our ever-growing national ambivalence toward the death penalty and its consequences.

And here we are now: States are running out of the drugs they need to execute people with and 152 death row exonerees are shedding light on the crumbling infrastructure of the justice system.

Perhaps, it’s a good time to leave the death penalty in the past, take it apart, and scatter its pieces like so many ashes.

Shares