June 28, 1969, was just another night in New York City. I had graduated from West Point only a few weeks earlier and was spending my graduation leave renting a loft down on Broome Street before I departed for three months’ training for the infantry officer basic course at Fort Benning, Georgia. I know . . . I know . . . what was a West Point graduate doing in a loft in SoHo? Well, truth be told, I was freelancing for the Village Voice that summer. I know . . . I know . . . what was a West Point graduate doing writing for the Village Voice in the summer of 1969 at the height of the Vietnam War? Well, I had started writing letters to the editor of the Voice while I was still a cadet and the year before had published my first couple of pieces in the paper. It wasn’t such a bad fit.

The three founders of the Voice, Dan Wolf, Norman Mailer, and Edwin Fancher, had all been infantrymen in World War II, and in an interesting twist of circumstance, Ed Fancher had served in the 10th Mountain Division under my grandfather, General Lucian K. Truscott Jr., in Northern Italy near the end of the war. Still, a West Pointer writing for the Voice was . . . unusual. But I was writing rock criticism — remember rock criticism? — and covering stuff that was all over the map. My first piece was on Christmas Day at the Dom on St. Marks Place with Wavy Gravy and the Hog Farm, soon to be made famous at Woodstock, and only the week before I had covered a Billy Graham religious revival at Madison Square Garden.

I wasn’t expecting to find a story when I left my loft at Broome and Crosby and walked toward the West Village, looking to spend the evening drinking at the Lion’s Head, the writer’s bar on Sheridan Square just off Seventh Avenue. It was a hangout for writers like Pete Hamill, then of the New York Post; Joe Flaherty, a former Brooklyn longshoreman currently writing for the Voice; David Markson, a novelist just making his mark; Nick Browne, the Lion’s Head bartender who covered the Village bar scene for the Voice; Fred Exley, who had just published the marvelous memoir “A Fan’s Notes”; and Joel Oppenheimer, the Village poet and graduate of Black Mountain College. Somehow I managed to fit into a scene that is still celebrated as a kind of golden age for Village writers with a drinking problem, or drinkers with a writing problem. Take your pick.

I was coming up Waverly Place from Sixth Avenue approaching Christopher Street when I saw the police car lights flashing. A cop car and a paddy wagon were pulled up in front of the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar two doors down from the Lion’s Head, and uniformed policemen were hauling Stonewall patrons out of the bar and putting them into the back of the paddy wagon. A crowd had gathered across the street, and some of the arrestees were pausing at the door and pursing their lips, doing as best as they could to blow kisses to the crowd with their hands cuffed behind their backs. I stopped to watch.

The crowd was young, some of them very young, the Stonewall being known for its underage crowd. In fact, it turned out that the purpose of the raid was to bust a Mob blackmail ring being run out of the Stonewall. The Mob was using underage hustlers to entrap older gay men, mainly from Wall Street, and extract money from them. All the gay bars in the Village were Mob owned. There was a “morals clause” in the New York State Liquor Authority laws that outlawed selling alcohol to “immoral” persons, which the authority arbitrarily defined as gay people, so they wouldn’t issue a liquor license to bars catering to gays. The Mob was happy to oblige, however, setting up illegal bars like the Stonewall and selling overpriced watered-down drinks to gays without a license and paying off the cops to stay open. It would take several years after Stonewall until the authority issued its first license to a bar with gay owners, the Ballroom on West Broadway, followed quickly by Reno Sweeney on 13th Street.

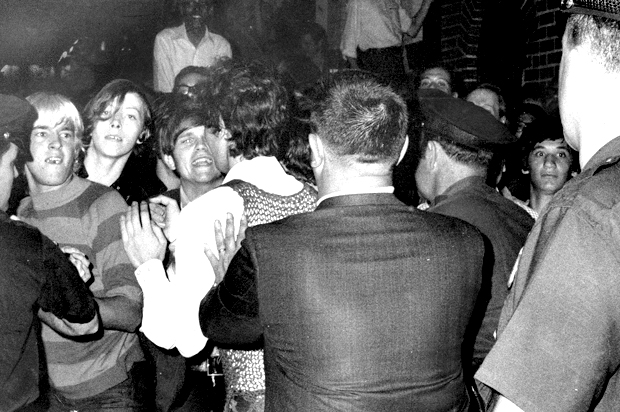

But on this night, gay bars were still illegal, and as they did every time they busted one, the cops were rounding up and harassing the patrons. The crowd outside was loving it as they came out striking poses, but the cops weren’t loving it. This was not the way gay people were supposed to act when they busted a bar. They were supposed to come out of the bar in cuffs with their heads down, hiding their faces in shame. But not this time. This time they were vamping and calling out to friends in the crowd.

The cops started angrily manhandling the arrestees, shoving them out the door and quickly into the paddy wagon. The guys under arrest were back talking the cops, asking them what their problem was, which only got the cops madder. Some of the crowd started throwing coins at the cops, taunting them. Then the cops pushed a drag queen out of the door of the Stonewall. She was apparently well-known on the street and paused to strike a vampy pose, acknowledging the crowd, calling out to a friend that she’d meet him when she got sprung from the Tombs in the morning. One of the cops pushed her roughly with a nightstick. She said something to the cop, he swung at her, she dodged the swing, and two more cops joined in, grabbing her and roughly shoving her into the paddy wagon.

That was it. Coins rained down. The crowd, which was now probably more than 100 strong, yelled at the cops, cursing them. Someone threw a beer can, and more trash rained down. The cops menaced the crowd, telling them to disperse. They didn’t. When the cops moved on them swinging their nightsticks, the crowd pushed back. Someone picked up a cobblestone and threw it through the window. The crowd yelled and rushed the Stonewall. One of the cops slammed the doors to the paddy wagon closed, it sped away, and the cops ran into the Stonewall and closed the door. The crowd was yelling at the cops, daring them to come out. The crowd had gotten bigger.

The whole street in front of the Stonewall was filled. I got up on a trash can next to the 55 Bar to see better. Someone threw another trash can through the Stonewall’s window. Someone else tried to grab my trash can, but I pushed them away. A guy right next to me lit a newspaper and threw it into the Stonewall window. I could see the cops inside struggling to put out the fire. Gay people were pissed off that the Stonewall had been busted and its patrons had been arrested and harassed by the cops. There was a riot going on. They weren’t going to take it anymore.

My friend the Voice columnist Howard Smith had gone into the Stonewall earlier to talk to the inspector in charge of the raid, Seymour Pine, and was trapped inside with the cops. The crowd kept throwing stuff at the Stonewall’s window. They pried a parking meter loose from the pavement and a couple of guys used it as a battering ram on the door, but the door held. The cops called for reinforcements and a few minutes later, maybe six cop cars came screaming down Christopher Street from Sixth Avenue. Cops jumped out swinging nightsticks and people started running, but they didn’t run far.

Some of them went around the corner of Seventh Avenue down West 9th Street and right on Waverly Place and came up behind the cops, taunting them with catcalls and curses. That split the cops, some chasing one group east down Christopher Street, some pursuing a crowd across the park, spilling onto West 4th and Grove Streets. Now there were several hundred people in the streets, the word having spread to gay bars around the Village which emptied into the streets and more people joined the protesters. More cops arrived, sirens screaming. The crowd kept dispersing in every direction and coming back to the Stonewall. Nobody was in charge. The only thing everyone knew was that it started at the Stonewall, and they weren’t giving up.

This went on for several hours until finally the cops got a sufficient number of reinforcements that they could hold the street in front of the bar and rescue those trapped inside. Jay Levin of the New York Post and I went over to the 6th Precinct around 4 a.m. I don’t recall the exact number, but I think something like 14 people were arrested. The cops wouldn’t give out any names, so my Voice story and Jay’s squib in the Post didn’t record who the heroes of Stonewall were. But they were there. I saw them. And I saw the gay people who poured out of the bars and clubs and took to the streets.

The next afternoon, the Stonewall reopened with a sign in the window saying something like “We got nothing but college boys and girls in here.” By dark, someone had spray-painted “Gay Power” over the sign. Crowds gathered on the street and it was on again. This time, the cops called in the TPF, the Tactical Patrol Force, with their plastic shields and helmets and plexiglass face masks. A lot of good that did. Word had spread to the boroughs and Fire Island that there had been a protest at the Stonewall on Friday night and the crowd was huge. The TPF didn’t know the twisting, crisscrossing streets of the Village at all, so the crowd had a grand time taunting the cops and leading them down alleys like Gay Street and Waverly Place and around the block.

About the time the cops arrived back at the front of the Stonewall and thought they had things in hand, a chorus line of protesters appeared behind them doing a kick routine, loudly singing, “We are the Stonewall girls!/ We wear our hair in curls!/ We don’t wear underwear!/ We show our pubic hair!” The TPF would wheel around and chase them, only to have another chorus line appear down the block singing out the same taunt. Soon tear gas canisters flew. People used wet rags and cups of water from hydrants to splash themselves and kept going. Every once in a while the cops would manage to grab one of the protesters and beat them with nightsticks and throw them in a car, but that only served to set off the crowd, which grew louder and larger as the night wore on. If the aim of the TPF was to disperse the riot and shame the gay people back into hiding, it didn’t work. By the wee hours, you could see gay guys walking home from Sheridan Square hand in hand. It was something you never saw on the streets until that night.

Sunday night the crowd was smaller and older, many people having arrived back in the Village from weekend places on Fire Island and upstate. The TPF tried to line up, blocking Christopher at Seventh Avenue, but other bars and businesses were open and complained, so they had to let people through. Occasionally, someone would throw trash at the cops and they would chase a group down the street, but there was no tear gas. The riot was over.

I spied the Warhol superstar Taylor Mead and Allen Ginsberg standing across Seventh Avenue and walked over. They had been out of town and wanted to know what happened, so I told them. Both longtime denizens of the East and West Village, they were amazed. Allen said he’d never been in the Stonewall and asked if I’d take him, so we walked over and went inside. The place had obviously been trashed by the cops, but the Mob guys had erected a makeshift bar and were back to selling overpriced drinks. Loud music was playing in the back room and people were dancing. Ginsberg asked me if I would dance with him, so we went back there and bopped around for a couple of songs and left.

Walking east across 8th St. toward Allen’s apartment, he continued to express amazement at what had happened. “The fags have lost that wounded look they always had,” he said of the people he’d seen on the streets. We passed couple after couple holding hands to Allen’s obvious delight. We reached Astor Place and as I turned south headed toward my loft, Allen called out, “Defend the fairies!” As I once observed elsewhere, as of that night, they didn’t need defending anymore.

As for me? Well, the brand-new second lieutenant of infantry went home to the loft and sat down and cluelessly wrote a story about how the “faggots” had rioted and asserted gay power for the first time. My piece, and one by Howard Smith, ran on the front page of the Voice that Wednesday. Jim Fouratt, who had been one of the protesters over the weekend and had quickly formed the Gay Liberation Front to give some political form to what he had clearly identified as a movement, held a demonstration in front of the Voice protesting my use of the word “faggot” to describe gay people. So the very first protest of the new gay movement was against me. The Voice committed to using “gay” from then on, and so did I. Gay power had come to Sheridan Square.