Certain films are plagued by a condition an ex-girlfriend of mine used to call "art up the butt." If you like this kind of thing, you know who you are and you know what I'm talking about.

You own books by William Burroughs and Michel Foucault (not that you've necessarily read them) and albums by Nick Cave and Sonic Youth. You know what is meant by the term "graphic novel" and you have opinions about it. You live in one of about two dozen North American neighborhoods where it's possible to buy a non-Starbucks latte and a nondubbed Hong Kong video. At some point in your life, you wore a pair of those little black kung-fu slippers.

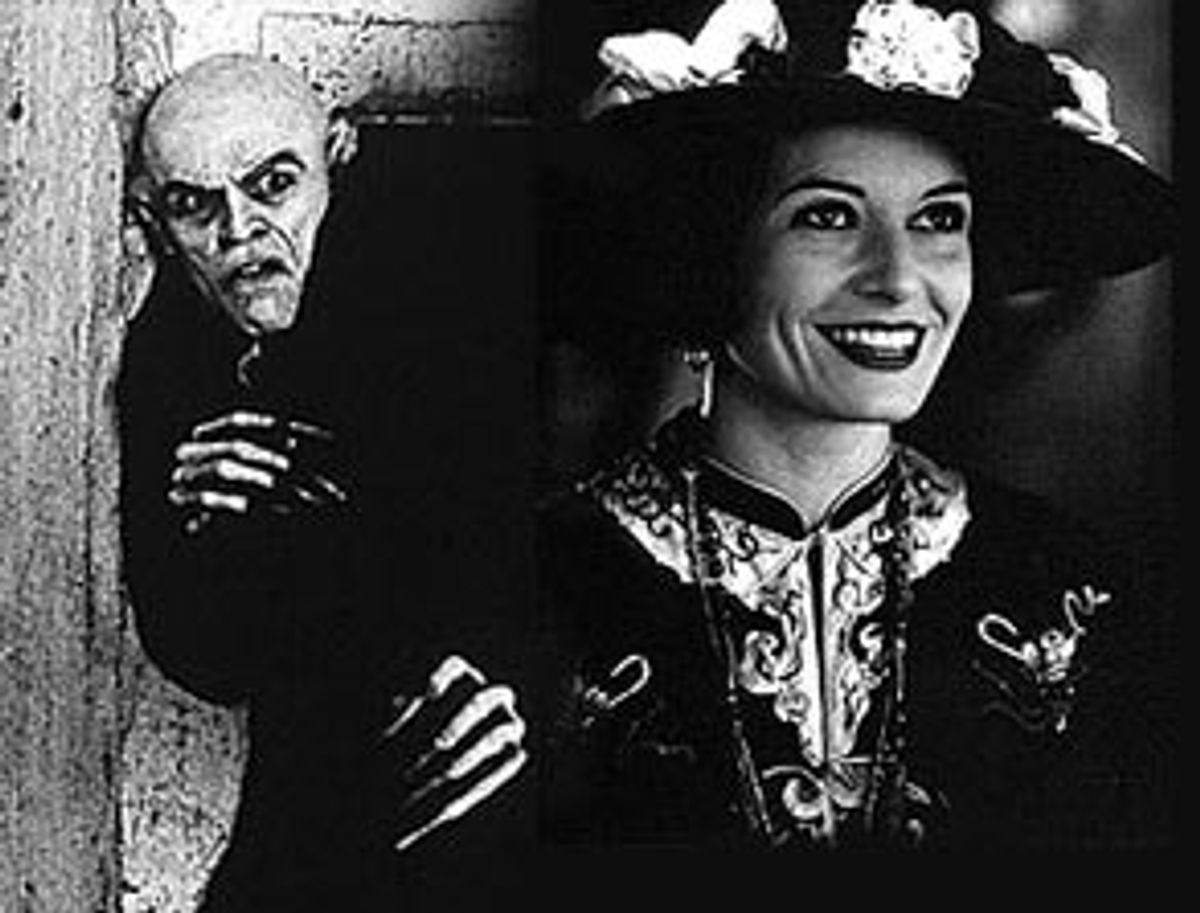

Any film with either John Malkovich or Willem Dafoe in it already has art at least halfway up the butt. When you get both of them plus film history plus vampires, the syndrome reaches near-toxic proportions. In "Shadow of the Vampire," Malkovich stars as legendary silent-film director F.W. Murnau; Dafoe, in ghoulish makeup, plays a genuine vampire hired to impersonate one in Murnau's 1922 classic "Nosferatu." The combination certainly sounds like the ultimate in '90s hipsterism, but all that this glum and slight entertainment manages to prove is that the '90s are over.

Naturally, if you fall into the demographic subgroup described above, the magnetism of the cast and premise will probably prove irresistible, no matter what I say. If not, don't say you weren't warned.

An art-up-the-butt avatar such as R.W. Fassbinder or Wim Wenders would have reveled in the archness and overripeness of this whole enterprise: Who is the real vampire -- the honest bloodsucker or the ruthless artist? As it is, Steven Katz's screenplay feels choppy and uncertain, but in hands like those its morphine-fueled pace and grandiose pronouncements about aesthetics might have been rendered into a languorous, decadent delight, chocolate with an absinthe center. E. Elias Merhige, an American director known for the underground film "Begotten" and his music videos for Marilyn Manson, can only manage a mildly amusing spoof with some striking images, a "Saturday Night Live" sketch for film students.

When "Shadow of the Vampire" is enjoyable, it's largely thanks to Malkovich, who plays Murnau as the brainier older brother of Joel Grey's sinister master of ceremonies in "Cabaret." Drifting through the set of his masterpiece like a distracted mad scientist, goggles askew on his forehead, he intones, "Our battle, our struggle, is to create art. Our weapon is the motion picture. Our poetry, our music, will have a context as certain as the grave."

Later, when his relationship with his living-dead "star" has gone sour, Murnau castigates the ancient bloodsucker in tones of consummate boredom. "Die alone, you vampire rat bastard," he says with no apparent emotion. "Moonchaser, blasphemer, monkey."

Dafoe does indeed look like a cross between a rat and a monkey as Max Schreck, whom Murnau hires to play the vampire Count Orlock. The historical Schreck was an obscure actor who left little trace of himself on the world beyond his memorable performance in "Nosferatu." In Katz and Merhige's version of events, there was no Schreck; the name was a convenient fiction to conceal the sinister deal Murnau made with the real Orlock, a filthy and desiccated vampire he discovered hiding in rural Czechoslovakia. In the interests of both science and art, Murnau would preserve Orlock on celluloid for posterity, and in return deliver him the tender neck of Greta Schroeder (Catherine McCormack), the film's depraved and delectable leading lady.

Hissing, shuffling his feet, eyeing the cast and crew with evident hunger, Dafoe's Schreck is a distinctively loathsome creation, with none of the erotic suavity of your typical Dracula. When Murnau becomes angry with him for attacking the cinematographer rather than, say, the script girl, Schreck sniffs the air with interest. "The script girl?" he says. "I'll eat her later."

In the film's single best scene, Schreck joins producer Albin Grau (Udo Kier) and screenwriter Henrick Galeen (John Aden Gillet) as they drink schnapps during a break in production. Amused by Schreck's method-actor refusal to break character, they ask him questions about life as a vampire. The novel "Dracula" made him sad, Schreck says. Vampires live alone so long that they become aristocrats without servants, he explains, detached from the details of human life. "Can he even remember how to buy bread? How to select wine and cheese?" For the first and nearly the only time, "Shadow of the Vampire" seems to be about its characters rather than its clever ideas.

As Merhige skips from the Jofa studios in Berlin to the Czech village where Murnau has Schreck concealed to the island of Heligoland, where the plots of both films reach their dénouements, he never establishes a guiding tone, or defines his characters clearly. Is Murnau ridiculous, evil or noble? Is Schreck/Orlock a monster, an object of pity or just a gag man? To what extent is "Shadow of the Vampire" intended as self-parody or farce? I found myself unable to answer these questions, but I do know that the "German" accents used by the entire cast are a heinous mistake. Kier at least has the excuse of being German, but there's no excuse for everybody else in the movie talking like Colonel Klink. (Schreck: "How you vould harm me ven even I don't know how I vould harm myzelf.")

Unable to control Schreck's predatory urges or to retreat from their bargain, Murnau presses forward toward his film's completion and a final confrontation with Schreck, sacrificing everything for art as the actors and technicians drop around him like flies. (Murnau, at the moment when Schreck finally gets his fangs into Greta: "Frankly, Count, I find this composition unworkable.")

Malkovich and Dafoe increasingly dominate the film, but their hambone acting, although entertaining in itself, comes to seem increasingly pointless. This is especially strange given Merhige's glimpses of how silents were actually shot, with the director essentially narrating the action while the actors improvise under his command. "Shadow of the Vampire" must be the most undisciplined film ever made about a tyrannical filmmaker.

Even if Murnau really was a self-important fop full of queeny pretentions (and even if he really hired a vampire), "Nosferatu" was one of the earliest and greatest accomplishments of supernatural cinema, and Merhige's film can't stand up to it. After the lovely opening credit sequence in imitation expressionist style, an overly chatty intertitle informs us that the "brilliant" Murnau became "one of the greatest filmmakers of all time." This calls to mind my seventh-grade creative writing teacher's advice: Show, don't tell. What Merhige actually shows us is a bloodless film about bloodlust, a horror comedy that's occasionally funny but is never frightening, an academic exercise driven by adolescent ideas that never shape themselves into a narrative: in short, a movie that can never dislodge the art fatally wedged up its butt.

Shares