Mel Ramos has a good life. He laughs when I tell him this, but I think he knows it's true. He's been an artist since the 1960s, and his work is in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Guggenheim, the Smithsonian and the Whitney; he's also had shows in major galleries around the world. He was a teacher for more than three decades (though he almost didn't make it through his first year after a student artwork depicting masturbation almost got him fired), he has a summer home in Spain and a family that he clearly adores.

But for all the acclaim Ramos has received and the obvious precision in the work, his demeanor is that of a guy having fun. He looks like Burt Reynolds' less-slick brother -- in fact, Playgirl once asked him to pose for a centerfold, just as they did Burt. (Mel said no.) His subject matter could be seen as risqué, except it's not. It's more humorous -- in a sexy way -- than erotic. "For me, that's what the work is about, not the nudity. Nudity doesn't imply sexuality to me. Nudist camps are asexual and nude beaches are asexual. What's important for me is the humor, the irony. I think it was Kenneth Clark who said that to be aroused by art is perverse."

Ramos was born in Sacramento, Calif., in 1935 to parents whose own parents had come from the same island in Portugal. When he was 15 he saw a picture by Salvador Dali in an art book and thought, I want to do that. He came up during a time when you had to be an abstract expressionist to pass your art classes, so he did that for awhile but it wasn't his passion.

In the early '60s, figuring he'd never have a career in art anyway, he decided to do the kind of art he loved -- figurative work that soon blended with what would later become pop art. One of his first major pieces was a drawing of Superman, followed by Batman and the superheroines.

Ramos had taken an art class from Wayne Thiebaud in junior college and respected his appreciation of history. "I remember the first day of class Wayne came in and his first assignment to us was to spell 'Cezanne.'" He took his Superman to Thiebaud for an opinion and found his mentor painting hot dogs. "I got reaffirmed that day," says Ramos.

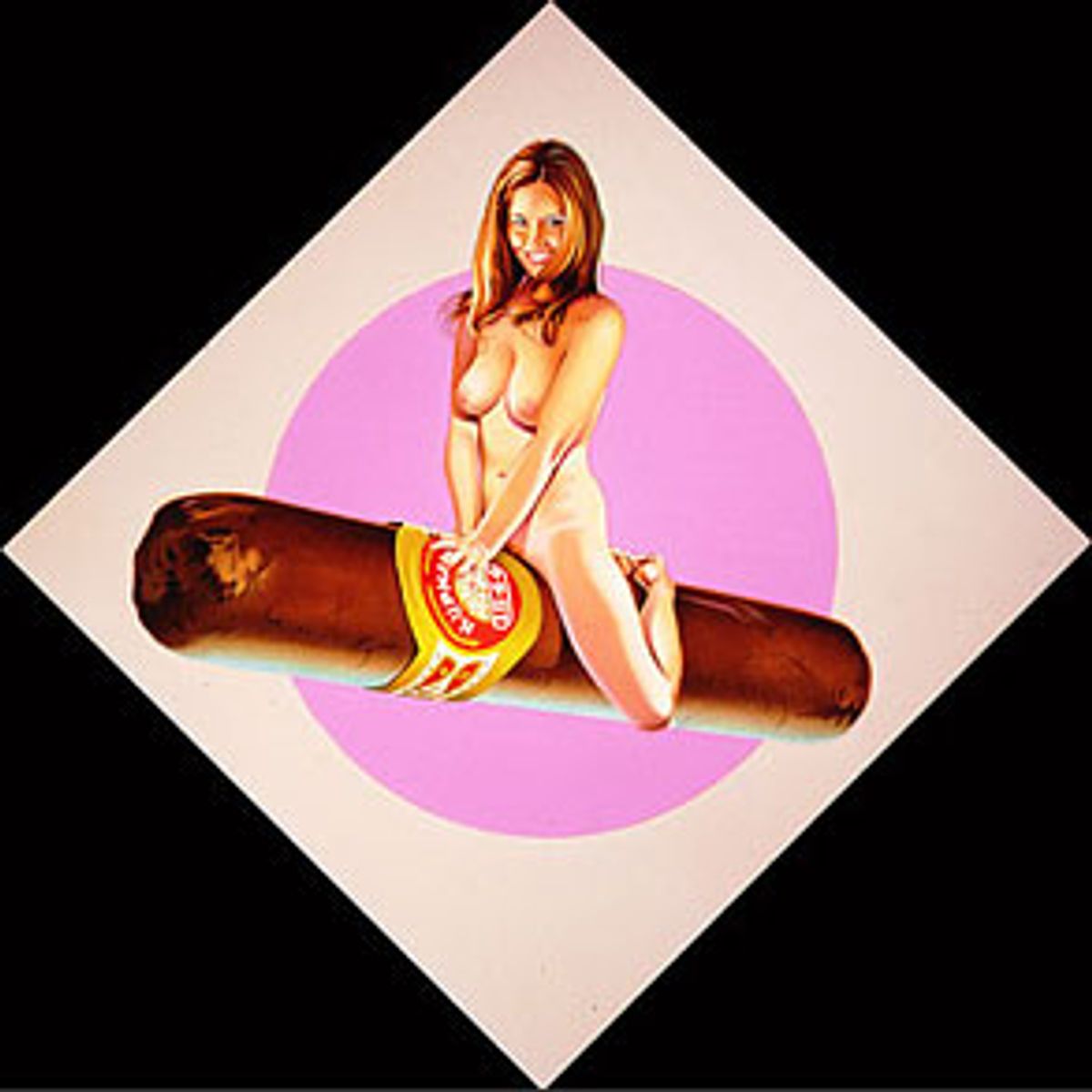

I met Mel Ramos at the Modernism Gallery in San Francisco, which is showing new paintings and works on paper through Dec. 21. The collection at Modernism is representative of Ramos' passions: everyday items like candy bars, cigars, golf balls and Cracker Jack boxes playfully combined with naked women. Ramos is also fond of the animal kingdom: he has painted voluptuous women riding on the back of a howling hippo or being pawed by a ferocious leopard. One of the central pieces at Modernism is a big-bosomed blonde babe emerging from a Mounds candy wrapper.

That looks like Cameron Diaz. Did you use a model or is it done from a photo?

It's Alma, the daughter of a friend of mine in Spain who makes wine. I start with digital collages -- I take one person's body, another's head, and a candy wrapper and work on the composition first on the Mac with Photoshop. Then I transfer it to the canvas or to a combination lithograph and silkscreen.

I see you like cigars ... [There are several works in the gallery depicting naked women riding Cuban cigars.]

I did an original work of a girl in a martini glass for Barnaby Conrad's book on martinis, so I did one for his book on cigars. I only smoke Cubans when I'm in Europe. It's expensive and a long way to go for a smoke!

Since a lot of your work is about naked women in suggestive poses, are you ever attacked by people calling you sexist?

Around 1978 at the University of Missouri one of my shows was picketed by a group of girls. Later at a lecture they were all in the front row and one raised her hand during the question period. I called on her and when I did, the whole row of them stood up and made a speech about me being a male chauvinist pig. Finally, way in the back an elderly woman stood up and said, "If you don't like his work, get out of here. I like it!" She saved me.

Do you still get criticized?

No, no, that's ancient history -- I hope! I mean, they were all saying I must hate women, but I don't spend my time, all my waking hours, painting something I hate. Do I look that stupid? My wife and my daughter have been models for me, and they are my strongest promoters. My daughter wants to quit her job to represent me, like Wayne Thiebaud's son represents him.

Speaking of Thiebaud, what do you think is the difference between his work and yours. You mentioned that a painting of his was just sold for $1.4 million. How much do yours go for?

My record price was $175,000.

Do you think he's a better artist than you are?

Yeah. He's a brilliant man. We started in the business of art together, but he had already had a career in it, working for Disney during World War II. He was my mentor; he's 15 years older than me ... he'll be 82 this month. I was fortunate enough to break away from his spell to be who I am. Many of his students didn't. But, you know, he also reached this level of success late in life.

Is there a place in the world where art is being done by people the way you and Thiebaud and the New York School did -- a place that is a hotbed of new talent not created by marketing?

No, I have spent a lot of time in Germany because I'm popular there, and Cologne is a creative city, but the last time I saw an artist with real spirit was [Jean-Michel] Basquiat. It was New York in the '80s.

Do you miss teaching?

I miss the students. I almost didn't make it, though. I had a reputation, I guess because of my work, and during my first, probationary year a student from another class did a piece that was a female figure masturbating with a Coke bottle. The president of the college wanted me fired because he said it was my influence on the student. The student wasn't even in my class! And that's not even a subject I would depict. But before I could get fired, his boss fired him for incompetency so I stayed for 31 years after that.

I've always been conservative about the business of art. I've never depended on it for my support. But teaching takes away from the art sometimes. Every artist I've known who has taught has told me the same thing: As soon as you get away from teaching your career will take off. It's been true for me. Since I quit in 1998 I've had more shows than ever, around the world.

Can you teach art?

No, you can't. You can teach drawing, painting. I can give you problems to solve, but you have to be motivated, dedicated.

Aren't some people just inherently talented when it comes to art?

No! I don't think so. Talent is hours.

Come on. You mean you don't think Michelangelo was just born with more talent than, say, the average truck driver?

He was a gay guy. They have more energy [laughs]. The only thing you are born with is the capacity for hard work, and if you are motivated to make art, you will.

You mean you don't think there is such a thing as innate talent?

I'm not sure what that means. Hard work, which comes from motivation, is what matters. If that truck driver decided he wanted to make art, he would.

OK. I don't think I agree, but I see what you mean. So, do you know what you'll do next? Do you ever have times when you aren't inspired?

I'm always inspired.

By what?

By beautiful women.

Did the Vargas girls inspire you? Your work looks similar to his.

Yes. Playboy called me up at one point when he was going to retire and asked me to take over, but I thought it wouldn't be a good idea to get typecast. But one reviewer did call my work "realism in drag." I thought that was good. They have also described it as "pinup." I see that as positive. I get lots of postcards and gallery announcements in the mail, but when I see one that looks like a pinup I pin it up on my wall!

Could you ever see yourself doing anything besides your art?

You never know. There are times when I wake up and think, I don't want to do this anymore. But everything else I would think of to do I want to do less.

Shares