Ronald Reagan’s presidency collapsed at the precise moment on Nov. 25, 1986, when he suddenly appeared without notice in the White House briefing room, introduced his attorney general, Edwin Meese, and instantly departed from the stage. Meese announced that funds raised by members of the National Security Council and others by selling arms to Iran had been used to aid the Nicaraguan Contras. Anti-terrorism laws and congressional resolutions had been willfully violated; eventually 11 people were convicted of felonies. In less than a week, Reagan’s popularity plunged from 67 percent to 46 percent, the greatest and quickest decline ever for a president.

On Dec. 17, 1986, the day William Casey, the mumbling director of the CIA, was scheduled to testify on the Iran-Contra scandal before the Senate Intelligence Committee, he collapsed into a coma, suffering from brain cancer, never to recover. Lt. Col. Oliver North, Casey’s action officer on the NSC, explained to members of a select congressional investigation that the profoundly conservative Casey had been the mastermind in creating an “overseas entity … self-financing, independent,” that would conduct U.S. foreign policy as a “stand-alone.” Called the “Enterprise,” it was the apotheosis of the Reagan doctrine, the waging of a global war for the rollback of communism.

The hard-line secretary of defense, Caspar Weinberger (who was later pardoned before his trial by President George H.W. Bush), and his neoconservative underlings were summarily dismissed, the NSC purged. “Let Reagan be Reagan” had long been the cry of conservatives. Now they screamed that Reagan was either being held prisoner or had sold out. “There was no Reagan revolution, only a Reagan rest stop,” wrote an editor of the National Review, the leading right-wing journal.

In interviews with investigators, Reagan said dozens of times he couldn’t recall what had happened. But he retained his utopianism and idealism that had propelled him from left-wing liberal in Hollywood to right-wing man on horseback, switching his ideologies but never his temperament.

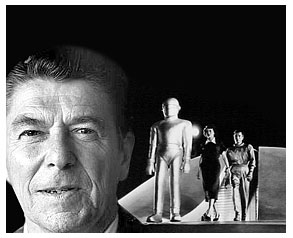

At his first meeting with new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in November 1985, Reagan had perplexed him by talking about how they might work together if there were an invasion of aliens from outer space. Colin Powell, who became the national security advisor in 1987 after the Iran-Contra scandal decimated the NSC, later revealed that he and others had tried to contain Reagan’s talk of “little green men,” as Powell put it. Reagan had got his idea from the 1951 science fiction movie “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” in which an alien warns of Earth’s apocalyptic destruction if nuclear weapons are not abolished.

At the October 1986 summit in Reykjavik, Iceland, Reagan had agreed to eliminate all nuclear weapons, to the consternation of his advisors, until Gorbachev insisted that testing for the Star Wars missile defense shield in outer space be suspended. Two of Reagan’s utopian dreams collided. But after the exposure of the Iran-Contra scandal, Gorbachev furiously rewrote the script, dropping the objection to Star Wars. (Nuclear physicist Andrei Sakharov told him it was a fantasy.) Instead, he crafted a practical arms reduction agreement, the Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty. Despite the opposition from ideological conservatives and “realist” conservatives, including Henry Kissinger and Reagan’s own vice president, George H.W. Bush, Reagan seized upon the treaty. He was encouraged by his ultimate handler, his wife, Nancy, who was also instrumental in empowering Secretary of State George Shultz to act as negotiator.

With script in hand, Reagan was Reagan again. In September 1987, he addressed the United Nations General Assembly: “I occasionally think how our differences worldwide would vanish if we were facing an alien threat from outside this world.” That December, Gorbachev came to the White House to sign the INF treaty. Reagan, through the succeeding months, kept musing, “What if all of us in the world discovered that we were threatened by a power from outer space, from another planet?” Then, in June 1988, Reagan, the arch-anticommunist, went to Moscow, where he declared that “of course” the Cold War was over and that his famous reference to the “evil empire” was from “another time.”

Reagan did not bring about the downfall of the Soviet Union, which was crumbling from terminal internal decay. But to the degree that he gave Gorbachev political time and space, he lent support to the liberalizing reform that hastened the end. In reaching out to Gorbachev, Reagan blithely discarded the right-wing faith that totalitarian communism was unchangeable and that only rollback, not containment and negotiation, would lead to its demise.

Reagan was acutely self-conscious about his about-face, and on his trip to Moscow he explained it in the terms with which he was most comfortable. “In the movie business actors often get what we call ‘typecast,'” he said. “The studios come to think of you as playing certain kinds of roles, and no matter how hard you try, you just can’t get them to think of you in any other way. Well, politics is a little like that too. So I’ve had a lot of time and reason to think about my role.”

Reagan’s embrace of Gorbachev rescued his own political standing. His rise in popularity to the mid-50 percent was essential in lifting his vice president’s presidential ambition, for elder Bush was moon to Reagan’s sun. Yet Bush distanced himself, adopting the realist’s view that Reagan suffered from “euphoria” and that nothing fundamental in the world was changing.

Now, President Bush eulogizes Reagan as his example. To the extent he was studying the Reagan presidency at the time, he took away the myths, not the lessons, of history. Bush has his own doctrine, a Manichaean battle with evildoers and an army of neoconservatives to lend complex rationalizations to his simplifications. Reagan was saved by the wholesale firing of the neoconservatives, the rejection of conservative dogma and a deliberate strategy to transcend his old typecasting. It is why he rose above his ruin, and rides, even in death, into the sunset of a happy Hollywood ending.